The Characters of "Cold Peace" -- Lt. Col. Graham Russel

When the Airlift started in June 1948, Berlin had just two receiving airfields, no concrete runway and only one obsolete power plant. Before the Airlift ended, concrete runways had been built at both Gatow and Tempelhof, a completely new airfield had been built at Tegel, and a modern power plant had gone up as well. These represented astonishing feats of engineering under the circumstances so including an engineer among my cast of characters seemed appropriate. The character of Lt. Colonel Graham Russel, CRE, was born.

Historically, the Royal Corps of Engineers genius responsible for improvising in the absence of nearly everything needed was a certain Lt. Col. R. Graham, but I knew nothing about him and so chose to create a fictional character Graham Russel. My character has found a home in the army after a childhood that left him stunted and deformed. Ugly of face and body, he has thrown himself into his work, finding friendship and satisfaction in the job he does. Fear of rejection has stopped him from seeking female companionship, and in the absence of family he takes his solace in gardening. He has over the years found it therapeutic.

An excerpt featuring Lt. Col. Graham Russel:

“So, sorry!” the cook called. “Wing Commanderis on water!” She gestured toward the still-visible sailboat.

“That’s all right,” Graham assured her. “Icame to do some gardening. Wing Commander Priestman said that I should talk toyou about that. I thought I might do some weeding for you.” He pointed to a bedof vegetables that looked in need of such service. Then remembering hismanners, he held out his hand to her. “My name’s Russel. Graham Russel. Pleasecall me Graham.”

She was momentarily taken aback but then brokeinto a wide smile which made her look much younger than he had thought her tobe. She shook his hand exclaiming, “Hello, Mr Graham. I’m Jasha. I see youbefore, no?”

Because of his misshapen body, people tendedto remember Graham, so he was used to being recognised. “Yes, I was here fordinner earlier in the week, which was when I saw and admired your garden. Youwouldn’t mind me helping you with it, would you?”

“No, no,” she agreed, but continued to lookpuzzled. Pointing to the garden, she asked hesitantly, “You want to workin garden?”

“Not for pay, just for the sake of doing it.”

She smiled at that. She was a pretty womanwhen she smiled, Graham thought, but she shook her head in protest too, “Youare important man. Not gardener.”

“I’m only important when I’m dressed up,”Graham answered. “Now, I’m just a gardener — if you’ll let me.” Although Jashanodded vigorously, Graham had the feeling she still didn’t fully understandhim. So, he tried a different tack. “Why don’t you show me what you’veplanted?”

“Yes, yes!” She lit up at that and started onthe tour at once. They progressed slowly through the extensive garden withJasha pointing things out and explaining when each crop would ripen or if therewere problems. She often reverted to German or Polish, but it didn’t matterbecause Graham was more interested in winning her trust than the details ofwhat she said. He nodded, asked sparse questions, commiserated over the problemof slugs, and praised what she had done. When they got the henhouse, Jashawaxed very eloquent – in Polish. Abruptly, she realised what she was doing andbroke off to laugh at herself. Graham laughed with her. When the laughter died,he pushed at one of the walls, causing it to sag and tilt. “The earth’s too wethere. We should move it to drier ground and shore it up a bit more.”

Jasha shook her head. “Wing Commander not wantchickens near house.”

Graham looked back toward the elegant housewith its wide terrace and French windows and had to agree. “Well, in that case,I could find some cinder blocks or bricks to use as piers to lift it off thewet ground.” She looked confused, so he explained with gestures and his patchyGerman until she nodded vigorously and smiled widely again.

As they walked back up the slope of the lawn, thedog came bounding up to shake himself beside them and then kept them companyback to the house. At the top of the garden, the dog separated himself to dryhimself on the warm flagstones of the terrace, while Graham again asked if hecould do some weeding, bending down to demonstrate his intent. This time, Jashaagreed, and Graham set to work.

Gradually, the day turned hot and muggy. Fromthe Havel came the sound of lapping water and the deep-throated chugging of bargescarrying goods from Gatow into the city or returning empty. The chickens cluckedcontentedly in their yard and now and again a crow called from the tall treeson the fringe of the property. The Dakotas droned overhead incessantly, and oneof the Sunderlands put down with a great splash as well. Graham watched all thefuss for a few minutes before resuming his weeding. Now and then, Jasha checkedup on him. They found it surprisingly easy to communicate because of theirshared interest in making things grow.

Graham had learned to love gardening when hewas a schoolboy. Because of his stunted legs, he was not able to take part in schoolsports, so his housemaster had suggested that he help the school gardener whenthe other boys were playing games. Thatway he was not entirely sedentary or lonely. He also got some fresh air andsunshine. The gardener had been Indian. He’d come to England decades earlierwith some former headmaster and had remained at the school after his benefactorhad died. He was wise, patient, and gentle, and he had filled Graham’s headwith a thousand Indian tales that made him want to see the world. He might havejoined the merchant navy if the war hadn’t come along.

Graham had been fourteen when the Great Warbroke out. His father returned to active service. His older brother hadvolunteered at once and been killed in ’15. Graham had volunteered as soon ashe turned 17, but they turned him down on medical grounds. He was not infantrymaterial. Six months later, they weren’t so picky. He’d been accepted and assignedto the sappers. He’d earned his commission by early ’18 and spent the rest ofthe war building roads and airfields. In the process, he became addicted to thecomradeship he’d found.

When the war ended, he did not want to leavethe army, so he took a permanent commission. In the interwar years, he’d servedacross the Empire: Palestine, Sudan, India, Singapore. He loved it all and hadnever felt lonely because he made friends everywhere he went. His friends welcomedhim into their homes, included him in their Christenings, birthday parties, weddings,and funerals. Occasionally, he’d allowed himself sentimental affections forgirls who never returned his feelings, and he’d learned to dismiss such lapsesin sanity as unimportant. He went on to new assignments, made new friends,laughed, partied, and tended the odd plant or two.

This last war had been harder, however. He’dserved primarily in Burma with the “forgotten army.” The murky politicalsituation, the climate, the terrain, the undeniable sense of being forgotten indeedby a government obsessed with fighting Germany, and the brutality of the enemyhad all taken their toll. It was in Burma that Graham had discovered gardening astherapy.

This garden, however, reminded him more ofgrowing up than battling the Japanese. The smell of the earth was different,and the insects were less aggressive. Graham found himself thinking ofretirement and a garden of his own. He’d been in the army for 31 years, andhe’d built an awful lot of airfields. The thrill of going to new places andfacing new challenges was fading. Many of his friends had already retired. Someto “warm climates” — Oman, Kenya and Cape Town. Or, more commonly, to homes inthe suburbs near “the grandchildren.” It was odd, Graham reflected; he hadnever missed having children as much as he missed having grandchildren. Ifnothing else, Berlin was turning into a tale to tell them about. Uncomfortably,he realized that for the first time in his service life, he felt lonely. He wascompletely free, and that was rather sad.

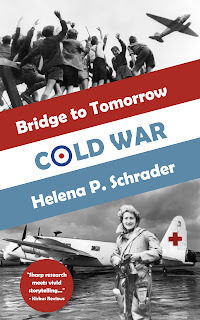

Graham does not feature as a major character until "Cold War."

Berlin is under siege. More than twomillion civilians must be supplied by air -- or surrender to Stalin's oppression.

USAF Captain J.B. Baronowsky and RAF FlightLieutenant Kit Moran once risked their lives to drop high explosives on Berlin.They are about to deliver milk, flour and children’s shoes instead. Meanwhile,two women pilots are flying an air ambulance that carries malnourished andabandoned children to freedom in the West. Until General Winter deploys on theside of Russia. Buy now!

Based on historical events, award-winning and best-selling novelistHelena P. Schrader delivers an insightful, exciting and moving tale about howformer enemies became friends in the face of Russian aggression — and how closethe Berlin Airlift came to failing.

Winning a war with milk, coal and candy!