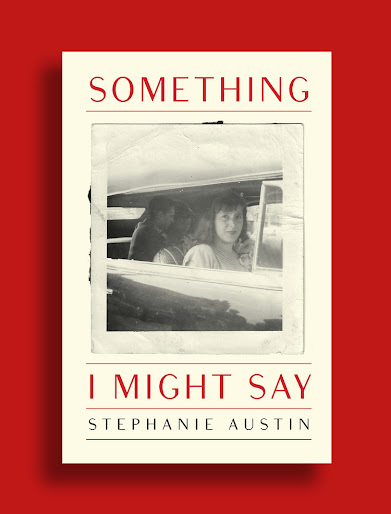

Stephanie Austin, Something I Might Say

When I was growing up inthe 1980s, my dad was a laborer. He wore flannel shirts and trucker hats andalways smelled like sweat, cigarettes, and beer. My dad had a friend namedStan, and we would all go to Stan’s house out in the woods in rural Illinois. Thisarea was thick with trees, which seemed like a jungle, and was full of smalllakes and rivers. Stan had a dog named Ribs, or maybe Bones. Something to dowith the skeleton. He lived beside a lake edged with sand, but my sister and I werenot allowed to walk barefoot there so we wouldn’t cut our feet on broken glass.My dad and Stan drank beer and built things together. My father surroundedhimself with other alcoholics.

Stan died in a drunk-driving accident. His car slid offan icy backroad and into a tree. My mom said Dad was drunk at the funeral. He situateda six-pack of beer and a hammer in Stan’s casket, angering Stan’s sister whoasked him to leave.

“Stan liked beer,” my dad said in defence. “I wanted tosend him off with something he liked.”

I’mjust now getting into Arizona writer Stephanie Austin’s full-length debut, theprose memoir

Something I Might Say

(Santa Rosa CA: WTAW Press, 2023), a slimvolume of sleek writing packed with complicated grief. Composed as five self-containedstories or chapters, the back cover offers: “Stephanie Austin had a complicatedfather and a complicated relationship with him. His death, after a short battlewith lung cancer, forced her to reckon with his always-threatened and nowpermanent absence from her life. Then the health of her grandmother, with whomshe had always been close, began to fail, and she faced another looming loss,intensified by the bewildering early months of the pandemic.” The prose isclear, unflinching; clearly describing the turmoils and details of losing aparent and then a grandparent, back to back, while mother to a four-year-old,and all beneath the shadow of Covid-19 pandemic. All of this, of course, morecomplicated due to the difficult relationship the author had with her father. Ifound elements of parent loss and the surrounding grief entirely familiar, asmy own father died within weeks of pandemic [see my essays in the face ofuncertainties], and Austin delves deep into the details of his erosion,death and all that followed. “He tried to cut his oxygen tubing. He said heneeded to cut the tybing to breathe. I told him no, it’s the opposite. I tookthe knives from his house. I took the scissors. I drove around with his knivesand scissors in my trunk.”

I’mjust now getting into Arizona writer Stephanie Austin’s full-length debut, theprose memoir

Something I Might Say

(Santa Rosa CA: WTAW Press, 2023), a slimvolume of sleek writing packed with complicated grief. Composed as five self-containedstories or chapters, the back cover offers: “Stephanie Austin had a complicatedfather and a complicated relationship with him. His death, after a short battlewith lung cancer, forced her to reckon with his always-threatened and nowpermanent absence from her life. Then the health of her grandmother, with whomshe had always been close, began to fail, and she faced another looming loss,intensified by the bewildering early months of the pandemic.” The prose isclear, unflinching; clearly describing the turmoils and details of losing aparent and then a grandparent, back to back, while mother to a four-year-old,and all beneath the shadow of Covid-19 pandemic. All of this, of course, morecomplicated due to the difficult relationship the author had with her father. Ifound elements of parent loss and the surrounding grief entirely familiar, asmy own father died within weeks of pandemic [see my essays in the face ofuncertainties], and Austin delves deep into the details of his erosion,death and all that followed. “He tried to cut his oxygen tubing. He said heneeded to cut the tybing to breathe. I told him no, it’s the opposite. I tookthe knives from his house. I took the scissors. I drove around with his knivesand scissors in my trunk.”Thecore of the collection emerges from grief, rippling out into the specifics of acentral idea most if not all of us will engage with at some point, especially throughthe losses of a parent or grandparent. When someone close to a writer dies, onecan imagine the advice (whether external or internal) becomes the mantra of “writethrough it,” and here, Austin does, allowing for a process that might otherwisebe so much more difficult. She writes of deathbed conversations, hospice care,health care professionals and funeral homes, and how grief is impossible to compartmentalizeor contain. “After he died,” she writes, “there was no place for my bitternessabout him, about men, about life, to go. No place for my righteous sense of emotionalabandonment. My dark, awful feelings had always been directed at him, and nowhe was gone, and those feelings hovered around me like ghosts.” Not long afterher father, she writes of her Grandma Sis, and the onset of an erosion, bothsudden and slow, through dementia.

My relationship with my father had been complicated,troubled, unhappy most of the time, and now, just weeks ago, his life hadended. Grandma Sis was not ending. She was injured. I argued with my mother: itshould be me who went back to collect her.

“Why?” she asked.

“Well, you know, because I could probably make thetransition for her a little smoother.” We both knew. Grandma Sis respondedbetter to me. My mother told me to stay home: my own daughter needed me.

Austin’sprose is exploratory, capturing the essence of the chaos that surrounds attendingcare, especially while simultaneously working and parenting, and aself-awareness throughout, enough to articulate elements of surprise, such as theend of the first piece, as she cleans her late father’s house:

In his nightstand, I found a pack of cigarettes stuffedinto a sock. I laughed and held them up to my husband. “Jesus Christ,” I said. “Helived alone. Who was he hiding these from?”