Wait a minute Mr Postman

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Ever since my nineteenth birthday card from my Aunty Marie failed to arrive, along with the enclosed £10 note, I have had an uneasy relationship with the postal service. But letters are a source of other forms of riches too, as the Post Office in Pictures exhibition, organized by the British Postal Museum and Archive (BPMA), at the beautiful Lumen URC reminds us.

The images on display, drawn mainly from the Post Office Magazine and Courier, document postal history from the 1930s onwards, focusing on the people that take our letters from A to B, come hell or high water – as this image of a mail cart bound for Holy Island in 1938 demonstrates:

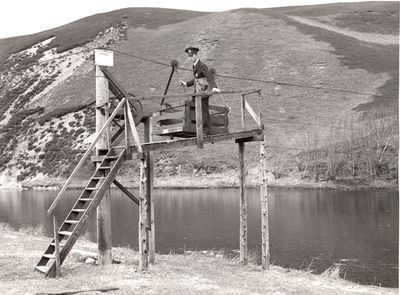

The “Bucket Bridge” (below), used to cross the River Findhorn in northern Scotland between 1939 and 1960, shows no small initiative.

These workers could only dream of the regulated efficiency of sending a letter from Barchester to Framley in Anthony Trollope’s fictional county of Barsetshire:

“… for that letter went into Barchester by the Courcy night mail-cart, which, on its road, passes through the villages of Uffey and Chaldicotes, reaching Barchester in time for the up mail-train from London. By that train, the letter was sent towards the metropolis as far as the junction of the Barset branch line, but there it was turned in its course, and came down again by the main line as far as Silverbridge; at which place, between six and seven in the morning, it was shouldered by the Framley footpost messenger, and in due course delivered at the Framley Parsonage exactly as Mrs Robarts had finished reading prayers to the four servants. Or, I should say rather, that such would in its usual course have been that letter’s destiny. As it was, however, it reached Silverbridge on Sunday, and lay there till the Monday, as the Framley people have declined their Sunday post. And then again, when the letter was delivered at the parsonage, on that wet Monday morning, Mrs Robarts was not at home.”

(What might have happened had these parcels required a signature is anyone’s guess.)

Trollope is one of the Post Office’s more high-profile employees. The Office provided material for his novels, from his early “hobbledehoyhood” working as a clerk on a salary of only £90 a year, to his appointment in 1859, after twenty-five years’s service, to the post of Surveyor of the Eastern District of England, with a salary of £700.

This is not to mention the role played by the postal service in the development of the epistolary novel. We can only wonder whether, without reliable deliveries, the genre could have reached such prominence as it did in the eighteenth century. What of Dracula and Frankenstein, were it not for the anonymous postman – or, transnational as the correspondences were, postmen – who carried the plot forward in their mail sacks? One feels emails might have quelled the suspense somewhat, and Captain Robert Walton’s mobile phone would certainly not have had signal in the North Pole.

Set this service to a tune and you get the Solent Male Voice Choir, formed in 1961 by a troupe of postmen who found, while sorting letters and parcels, musical inspiration. They will be performing as part of the exhibition, at Lumen on Saturday, August 18, at 7pm.

Perhaps, considering everything the postal service has done over the years, I might finally let that £10 slide.

(All pictures are courtesy of the Royal Mail Group Ltd / The British Postal Museum & Archive.)

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers