The music of summer

Enjoying lunch and the view in Bemus Pt, a classic lakeside resort town on Chautauqua Lake in NY state – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Enjoying lunch and the view in Bemus Pt, a classic lakeside resort town on Chautauqua Lake in NY state – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Sweet Rosie O’Grady,

My dear little Rose,

She’s my steady lady,

Most ev’ryone knows.

And, when we are married,

How happy we’ll be;

I love sweet Rosie O’Grady,

And Rosie O’Grady loves me.

Fairgrounds have always been as much about the sights and sounds as the attractions – the clacking of rides, shouting of barkers, children’s (and adults’) screams and laughter, and the music drawing rider onto the carousel.

The lyrics above are from a popular fairground piece of music written by Maude Nugent, an American singer and composer. She composed and wrote the lyrics to “Sweet Rosie O’Grady” in 1896 and sold the song to Tin Pan Alley publisher Joseph W. Stern & Co. (Tin Pan Alley was a well-known group of songwriters and music publishers in New York City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.) It became one of the most popular waltz standards of the time, its sheet music selling over a million copies. In 1949 she even performed it on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Nugent wasn’t the only composer by far whose music made onto player pianos and carousel organs, as well as the travelling military band organs – Scott Joplin, Thomas ‘Fats’ Waller, Gustav Mahler and Liberace were just a few of the many well-known composers who graced the fair grounds.

Fairs, in their purest form as local festivals, have been around since Roman times at least. They evolved into more permanent places of entertainment in Europe as ‘pleasure gardens’, and also world fairs, both of which gave rise to amusement parks, with rides, games of “chance and skill”, thrill acts, and food and merchandise stalls, much as they still are today. Music was added, and as the rides became mechanized and the crowds large, fairground organs were developed that could play quite loudly above all the ambient noise.

These organs were designed to accompany various rides and attractions, but primarily carousels. The organs were designed to replicate the capabilities of a human band – hence their common name in the U.S., band organs.

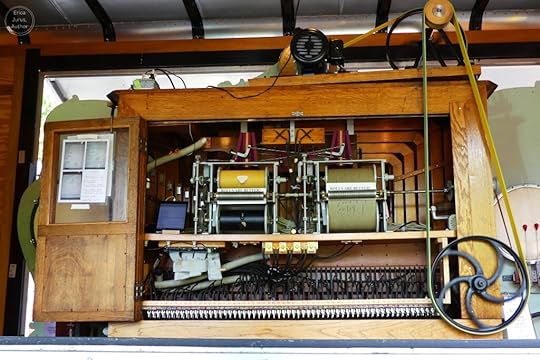

Artizan travelling military band organ at the Herschell Factory Museum in N. Tonawanda, NY – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Artizan travelling military band organ at the Herschell Factory Museum in N. Tonawanda, NY – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedEarly organs were played by a similar system to music boxes: a rotating barrel with the sounds triggered by metal pins.Later organs used punched strips of cards called ‘book music’. These then developed into music rolls – rolls of perforated paper with the music encoded into markings that the automatic reader system could recognize.

Watching these old organs pour out a remarkable amount of sound is fascinating. They use a series of pipes that sit on top of a hollow wind chest. The wind chest shoves air into a pipe, which causes the air to oscillate and produce a sound. Groups of pipes, called ‘ranks’, contain knobs that activate a slider under specific sets of pipes. These are known as ‘stops’ – they allow air to flow through the pipes to make a sound. The expression “pulling out all the stops” comes from doing this on an organ to allow every pipe to make noise.

The air comes from bellows that pump it in compressed form into the wind chest, which itself contains a series of valves (pallets) connected to either a keyboard (in a regular organ) or to the device which reads the punches on a music roll in player pianos and organs. On band organs, a wheel at the back of the organ turns a crankshaft that operates the pump stick driving the bellows. Many people call a band organ’s music “the happiest music on earth.”

The three different types of band organs – those operating on a cylinder, called barrel organs, book organs that use folded cardboard books for the music, and those operating on paper music rolls – each produce a different kind of sound.

Eugene de Kleist was an early builder of barrel organs for use in carousels in North Tonawanda, New York. Wurlitzer bought an interest in his Barrel Organ Factory in 1897, and a few years later Wurlitzer bought the entire operation, moving all Wurlitzer manufacturing from Ohio to the New York site. From 1914 to 1942, Wurlitzer built over 2,243 pipe organs in the new factory.

They also built jukeboxes, which became the iconic jukebox of the Big Band era, and theatre organs. The “Mighty Wurlitzer” theatre organ was introduced in late 1910; it became their most famous product. Wurlitzer theatre organs were installed around the world in theatres, churches, museums and private homes.

The largest Wurlitzer organ originally built was the 58-rank instrument at Radio City Music Hall in New York City. It’s actually a concert instrument, capable of playing a classical repertoire as well as non-classical music.

Fairground organs are typically run by wind under pressure, generated from mechanically powered bellows in the instrument’s base. In the photo above, you can see the bellows at the base of the organ, being run by a pulley and belts. These instruments are keyboard-less (except for a few rarer configurations with one or more accordions, whose keys could be seen to move).

With the advent of computer control, some band organs have been built or converted to be played electronically, but I prefer the nostalgia of the original instruments, where you can watch the rolls of music scroll through their holders, and even see the perforations work their magic. On this organ at the Herschell Factory Museum, I watched 4 short perforations in sequence make the little stick on the white snare drum pound out a flurry of beats.

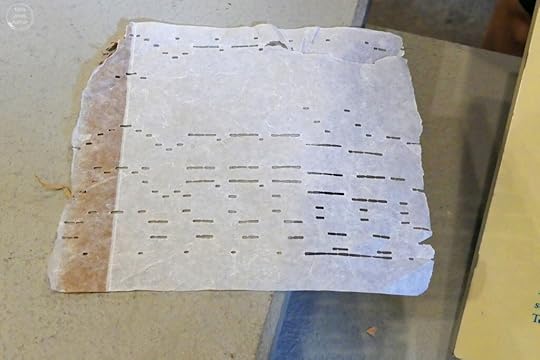

Music books and rolls were essentially early media storage devices. Music rolls were invented by Gavioli & Cie, an organ builder company in Italy and France. The rolls were more compact and cheaper to make than book music. Both books and rolls ran with different operating actions that read the music either with air pressure, suction, or mechanically, using a sensing device called a tracker bar, that would then play the instrument.

A desk at the Herschell Factory where music pieces were arranged and marked onto rolls of paper, to be transferred by punches to the actual music rolls, as seen below – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

A desk at the Herschell Factory where music pieces were arranged and marked onto rolls of paper, to be transferred by punches to the actual music rolls, as seen below – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Punches in different sizes to make the musical notations on the music rolls – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Punches in different sizes to make the musical notations on the music rolls – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedAfter rolls are played, they have to be rewound before they can be played again, like the defunct VHS video tapes that played stored TV shows and movies. To overcome this break in a musical performance, some instruments were built with two player mechanisms (called a ‘duplex roll’), allowing one roll to play while the other rewound. To extend the longevity of the storage pieces, mechanically-read cardboard book music was typically fortified with an application of shellac, while music rolls were made with moisture-resisting paper stocks.

A sample of music roll, illustrating some of the notations and how thin the paper actually is – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

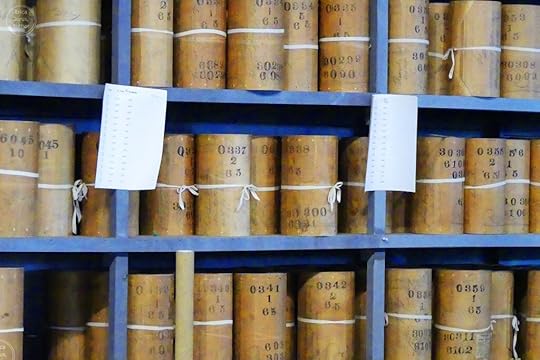

A sample of music roll, illustrating some of the notations and how thin the paper actually is – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved Shelves upon shelves of preserved music rolls, still being used, at the Herschell Factory Museum – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Shelves upon shelves of preserved music rolls, still being used, at the Herschell Factory Museum – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedThe organ workings were typically covered with an ornate decorative façade that was designed to attract attention, as was the case with most fairground equipment – making the equipment its own bright advertisement.

The case facades were often adorned with percussion instruments such as snare drums as well as animated human figures such ‘conductors’ whose arms moved in time to the music, or women striking bells, that provided visual entertainment as they played.

Magnificent band organ under restoration at the Herschell Factory Museum, showing an elaborate trumpet system as well as the front of one of the snare drums on each side – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Magnificent band organ under restoration at the Herschell Factory Museum, showing an elaborate trumpet system as well as the front of one of the snare drums on each side – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedWurlitzer partnered with George Herschell, James Armitage and other businessmen from the area, and constructed a separate plant in downtown North Tonawanda. It manufactured organs and hurdy-gurdies for amusement parks, carnival midways, circuses and roller rinks, and assembled amusement rides, particularly carousels, right at the factory.

Wurlitzer had early success from defense contracts to provide musical instruments to the U.S. military, which I’m assuming gave rise to some organs – including the one that greets visitors majestically at the Herschell Factory Museum – being labelled as ‘military band organs’. Its theatre organs were popular in movie houses during the days of silent movies. The company also had a chain of retail stores where consumers could buy their products.

The music of carousels and band organs truly is the music of summertime, and happily you can still find it in thriving amusement parks and carousels around the world.

So, there’s a piece of the story behind the Llithfaen carousel in my Chaos Roads Trilogy – but not all of it by a long shot. The strangeness of that carousel begins to emerge in Book 2, Into the Forbidden Fire, that is now available in paperback and ebook on Amazon. The final novel in the trilogy will reveal the final details…

In the meantime, take the opportunity to explore and enjoy these charming remnants of a time gone, but definitely not forgotten, and the modern amenities that round out the pleasure of a leisurely summer day.

Fish tacos and coleslaw at the Ellicottville Brewing Co. restaurant in Bemus Pt, NY – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

Fish tacos and coleslaw at the Ellicottville Brewing Co. restaurant in Bemus Pt, NY – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved A frosty “adult” milkshake at the restaurant, made with Oreo Cookies and Skrewball Peanut Butter Whiskey – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reserved

A frosty “adult” milkshake at the restaurant, made with Oreo Cookies and Skrewball Peanut Butter Whiskey – photo by E. Jurus, all rights reservedThe post The music of summer first appeared on Erica Jurus.