Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between I: The Weird Tale – Rafe McGregor

The first of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by framing first thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post introduces the weird tale.

Wyrd, Weyrd, Weird

‘Weyrd’ came to Middle English in the fifteenth century from the OldNorse urðr via the Anglo-Saxon wurd and Old English ‘wyrd’. Itsmeaning in the ancient languages was twofold, denoting both personal destiny and thepersonification of personal destiny in the three deities that tended Yggdrasil(the Norse tree of life), who were known as the Norns. A thinly-disguisedversion of the Norns appears in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (first performedin 1606), where they are called the ‘weyrd’ or ‘weyward’ sisters, i.e. witches(like his contemporaries, Shakespeare had little interest in consistentspelling, including the writing of his own name). The Oxford EnglishDictionary identifies four distinct but related meanings of ‘weird’ inModern English:

1. Having or claiming to havethe power to control the fate or the destiny of human beings.

2. Suggestive of unearthlycharacter or strangeness that is unaccountable or uncomfortable.

3. Having a strange or unusualappearance.

4. Out of the ordinary, odd,fantastic.

We can summarise these by conceiving of ‘the weird’ as supernaturalrather than natural and uncommon rather than common, but this isn’tparticularly helpful when it comes to identifying a category or genre offiction. Almost all speculative fiction, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein;or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune series(2021, 2024), could be described as supernatural and/or uncommon.

A popular route out of this impasse is to identify the weird with theuncanny. Writing for The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman compares King, Lovecraft,and Kafka: ‘Still, when you’re in the presence of the genuine, uncanny article,you know. Stephen King is tremendously imaginative, but H.P. Lovecraft is weird;Kafka is probably the ultimate weird writer.’ The concept of the uncanny as itis commonly used today, particularly with respect to literary criticism, is atranslation of Sigmund Freud’s Das Unheimliche, which was introduced inan essay published in 1919. Directly translated, ‘unheimlich’ means ‘notfrom the home’ and some critics prefer to use the more direct ‘unhomely’. InFreud’s essay, the uncanny is the return of the repressed and he explains it bymeans of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s short story, ‘The Sandman’ (1817), and Otto Rank’s TheDouble (published in 1925, but written in 1914), a psychoanalyticexploration of the doppelgänger. The core of Freud’s conception of theunhomely is that something can be simultaneously familiar and alien. In hisauthoritative The Uncanny (2003), Nicholas Royleidentifies Martin Heidegger as providing the most intense philosophicalexploration of the concept. The very premise of Heidegger’s magnum opus, Beingand Time (1927), is that what we take to be ordinary is in factextra-ordinary and uncanny. Dasein (which can be translated as ‘being-here’or, to use less abstruse terminology, ‘agency’ or ‘selfhood’) is fundamentally‘not-at-home’ in the world and Dasein itself is thus uncanny, inconsequence of which we experience Angst (anxiety). Like China Miéville and Mark Fisher, however, I don’t thinkthat the uncanny gives us the answer to what weird fiction is.

Romanticism to Modernism

Unlike Miéville, I do think that the origins of weird fiction can befound in Gothic Romanticism. In medieval art, Gothic style was distinguishedfrom Classical style by its abandonment of restraint and subtlety, deployingcaricature and exaggeration to evoke strong emotions and created with theintention of expressing the artist’s emotion rather than representing the realityin which the artist lived. As an artistic movement, the Gothic survived thetransition from the medieval to the modern in the form of architecture,specifically the Gothic Revival or Neo-Gothic that became popular in theseventeenth century. The Gothic focus on emotion, expression, and evocation meantthat interest was revived once again with the development of Romanticism acentury later. The Romantic movement elevated the significance of emotion,expression, and individualism and prioritised the natural over the industrialand the medieval over the modern. Unsurprisingly, the Romantic movement saw thedevelopment of the English novel from an experimental to an established artform and Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) is regarded asthe first work of Gothic fiction. The genre reached its apotheosis withShelley’s Frankenstein which, in turn, influenced two distinct sets ofnineteenth century precursors to weird fiction, one on each side of theAtlantic. I should mention at this point that this series will focusexclusively on the Anglophone weird, in consequence of the combination of myown ignominious monolingualism, the consolidation of the genre in America’spulp magazines in the first half of the twentieth century, and the continueddominance of English as the preferred language of its authors. This restrictionmeans that I exclude at least one exemplary author of weird fiction, FranzKafka (1883-1924). As one of the leading lights of Modernist literature, Kafkais rarely linked to pulp, popular, or genre fiction, but I agree completelywith Rothman’s characterisation.

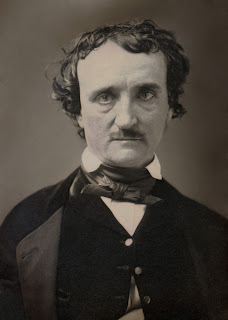

In the US, the crucial link between Gothic Romanticism and weird fictionis, of course, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849, pictured). Poe was one of the firstmasters of the short story and I regard his ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’(published in Graham’s Magazine in 1841) as the origin of both crime fictionand weird fiction. Poe was succeeded by Ambrose Bierce (1842-c.1914), MadelineYale Wynne (1847-1918), and Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933). The tradition inthe UK (actually Ireland, which was part of the UK at the time) emerged with thework of Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), who retains a reputation as one of thegreatest ghost story writers in English. Le Fanu was succeeded by Violet Paget(1854-1933, writing under the penname Vernon Lee, pictured), Conan Doyle (1859-1930),and M.R. James (1862-1936). Doyle is often underrated as a writer of horror andI have attempted to redress this imbalance in The Conan Doyle Weirdbook (2012). Ramsay Campbell claims that H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937)united and advanced the traditions in which Poe and Le Fanu were working andLovecraft acknowledged his debt to both traditions in his literary criticism.Campbell regards Lovecraft’s Mythos (which he prefers to call the Lovecraftrather than Cthulhu Mythos) as evidence of his lifelong attempt to perfect theweird tale, which involved an experimentation with prose comparable to his morelauded contemporaries in Modernist literature, such as Virginia Woolf, JamesJoyce, and Kafka. If not a part of Modernism, the weird tale is, at the veryleast, an epiphenomenon of it.

Weird Worldviews

I still haven’t answered the question of what weird fiction is or what itwas Lovecraft spent his life trying to perfect. There was little critical oracademic interest in the weird until the turn of the century and that interestis largely the result of the efforts of literary critic S.T. Joshi, who spentthe last decade of the twentieth century pioneering the field of weird fictioncriticism. In 1990, he published The Weird Tale, which was the first of hismany monographs on the genre and remains the most authoritative critical studypublished to date. Joshi identifies the weird tale as a retrospective categoryof speculative fiction that was published from 1880 to 1940 and is essentiallyrather than superficially philosophical in virtue of presenting or representinga fully-fledged and fleshed-out worldview. Although alternative definitions ofthe weird in terms of the sublime, the uncanny, and the disgusting have beenproposed, Joshi’s remains the most compelling. Lovecraft was a prolific –perhaps even compulsive – letter writer and defined his own oeuvre as cosmic horror,in which ‘common human laws and interests are emotions that have no validity orsignificance in the vast cosmos-at-large’. What distinguishes Lovecraft fromhis contemporaries, such as Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951, pictured) and Edward Plunkett (1878-1957,writing under his aristocratic title Lord Dunsany), is thus the absenceof the supernatural. Lovecraft’s monsters are not werewolves, vampires, orghosts, but aliens (although humanity is unable to distinguish the two). In hisout-of-print biography of Lovecraft, L. Spraque de Camp referred to theworldview on which Joshi places so much emphasis as ‘futilitarianism’.Lovecraft denied that he was a pessimist in another of his letters: ‘I am not a pessimist but an indifferentist – that is, I don’t makethe mistake of thinking that the resultant of the natural forces surroundingand governing organic life will have any connexion with the wishes or tastes ofany part of that organic life-process.’

With the exception of James, Joshi argues that each of the six exemplarsof the weird tale – Bierce, James, Arthur Machen (1863-1947), Blackwood, Plunkett, andLovecraft – had . I havealready suggested that Bierce and James are more accurately considered as precursorsto the weird and I think Joshi errs in omitting William Hope Hodgson(1877-1918) from his list. I came to Lovecraftmuch later than most – in my thirties – and have read his work in three cyclesin the last two decades. In the first, I was amazed, enthralled, and evenshocked by his singularity, innovativeness, and complexity. My second readingwas much more critical, identifying flaws in both his form (structure anddialogue) and content (pathological racism and casual sexism) and wondering howand why he remains so popular. More recently, I’ve come to see him as a genius for all his moral and artistic flaws, a literary equivalent of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche: two awkward, unhappy, and rather unpleasant men whose talent was unrecognised while they were alive, but whose posthumous influence is too great to calculate with any accuracy.

Recommended Reading

Edgar Allan Poe, The Murdersin the Rue Morgue, Graham’ s Magazine (1848).

Algernon Blackwood, TheWillows, The Listener and Other Stories (1907).

H.P. Lovecraft, The Call ofCthulhu, Weird Tales (1928).

Nonfiction

S.T. Joshi, The WeirdTale, Hippocampus Press (1990).

Kate Marshall, Novels byAliens: Weird Tales and the Twenty-First Century, The University of ChicagoPress (2023).

Michael Dirda, Introduction,Weird Tales, The Folio Society (2024).