Reproducing a Java 21 virtual threads deadlock scenario with TLA+

Recently, some of my former colleagues wrote a blog post on the Netflix Tech Blog about a particularly challenging performance issue they ran into in production when using the new virtual threads feature of Java 21. Their post goes into a lot of detail on how they conducted their investigation and finally figured out what the issue was, and I highly recommend it. They also include a link to a simple Java program that reproduces the issue.

I thought it would be fun to see if I could model the system in enough detail in TLA+ to be able to reproduce the problem. Ultimately, this was a deadlock issue, and one of the things that TLA+ is good at is detecting deadlocks. While reproducing a known problem won’t find any new bugs, I still found the exercise useful because it helped me get a better understanding of the behavior of the technologies that are involved. There’s nothing like trying to model an existing system to teach you that you don’t actually understand the implementation details as well as you thought you did.

This problem only manifested when the following conditions were all present in the execution:

virtual threadsplatform threadsAll threads contending on a locksome virtual threads trying to acquire the lock when inside a synchronized blocksome virtual threads trying to acquire the lock when not inside a synchronized blockTo be able to model this, we need to understand some details about:

virtual threadssynchronized blocks and how they interact with virtual threadsJava lock behavior when there are multiple threads waiting for the lockVirtual threadsVirtual threads are very well-explained in JEP 444, and I don’t think I can really improve upon that description. I’ll provide just enough detail here so that my TLA+ model makes sense, but I recommend that you read the original source. (Side note: Ron Pressler, one of the authors of JEP 444, just so happens to be a TLA+ expert).

If you want to write a request-response style application that can handle multiple concurrent requests, then programming in a thread-per-request style is very appealing, because the style of programming is easy to reason about.

The problem with thread-per-request is that each individual thread consumes a non-trivial amount of system resources (most notably, dedicated memory for the call stack of each thread). If you have too many threads, then you can start to see performance issues. But in thread-per-request model, the number of concurrent requests your application service is capped by the number of threads. The number of threads your system can run can become the bottleneck.

You can avoid the thread bottleneck by writing in an asynchronous style instead of thread-per-request. However, async code is generally regarded as more difficult for programmers to write than thread-per-request.

Virtual threads are an attempt to keep the thread-per-request programming model while reducing the resource cost of individual threads, so that programs can run comfortably with many more threads.

The general approach of virtual threads is referred to as user-mode threads. Traditionally, threads in Java are wrappers around operating-system (OS) level threads, which means there is a 1:1 relationship between a thread from the Java programmer’s perspective and the operating system’s perspective. With user-mode threads, this is no longer true, which means that virtual threads are much “cheaper”: they consume fewer resources, so you can have many more of them. They still have the same API as OS level threads, which makes them easy to use by programmers who are familiar with threads.

However, you still need the OS level threads (which JEP 444 refers to as platform threads), as we’ll discuss in the next session.

How virtual threads actually run: carriersFor a virtual thread to execute, the scheduler needs to assign a platform thread to it. This platform thread is called the carrier thread, and JEP 444 uses the term mounting to refer to assigning a virtual thread to a carrier thread. The way you set up your Java application to use virtual threads is that you configure a pool of platform threads that will back your virtual threads. The scheduler will assign virtual threads to carrier threads to the pool.

A virtual thread may be assigned to different platform threads throughout the virtual thread’s lifetime: the scheduler is free to unmount a virtual thread from one platform thread and then later mount the virtual thread onto a different platform thread.

Importantly, a virtual thread needs to be mounted to a platform thread in order to run. If it isn’t mounted to a carrier thread, the virtual thread can’t run.

SynchronizedWhile virtual threads are new to Java, the synchronized statement has been in the language for a long time. From the Java docs:

A synchronized statement acquires a mutual-exclusion lock (§17.1) on behalf of the executing thread, executes a block, then releases the lock. While the executing thread owns the lock, no other thread may acquire the lock.

Here’s an example of a synchronized statement used by the Brave distributed tracing instrumentation library, which is referenced in the original post:

final class RealSpan extends Span { ... final PendingSpans pendingSpans; final MutableSpan state; @Override public void finish(long timestamp) { synchronized (state) { pendingSpans.finish(context, timestamp); } }In the example method above, the effect of the synchronized statement is to:

Acquire the lock associated with the state objectExecute the code inside of the blockRelease the lock(Note that in Java, every object is associated with a lock). This type of synchronization API is sometimes referred to as a monitor.

Synchronized blocks are relevant here because they interact with virtual threads, as described below.

Virtual threads, synchronized blocks, and pinningSynchronized blocks guarantee mutual exclusion: only one thread can execute inside of the synchronized block. In order to enforce this guarantee, the Java engineers made the decision that, when a virtual thread enters a synchronized block, it must be pinned to its carrier thread. This means that the scheduler is not permitted to unmount a virtual thread from a carrier as long as the virtual thread until the virtual thread exits the synchronized block.

ReentrantLock as FIFOThe last piece of the puzzle is related to the implementation details of a particular Java synchronization primitive: the ReentrantLock class. What’s important here is how this class behaves when there are multiple threads contending for the lock, and the thread that currently holds the lock releases it.

The ReentrantLock class delegates the acquire and release logic behavior to the AbstractQueuedSynchronizer class. As noted in the source code comments, this class is a variation of a type of lock called a CLH lock, which was developed independently by Travis Craig in his paper Building FIFO and Priority-Queueing Spin Locks from Atomic Swap, and by Erik Hagersten and Anders Landin in their paper Queue locks on cache coherent multiprocessors, where they refer to it as an LH lock. (Note that the Java implementation is not a spin lock).

The relevant implementation detail is that this lock is a FIFO: it maintains a queue with the identity of the threads that are waiting on the lock, ordered by arrival. As you can see in the code, after a thread releases a lock, the next thread in line gets notified that the lock is free.

Modeling in TLA+The sets of threadsI modeled the threads using three constant sets:

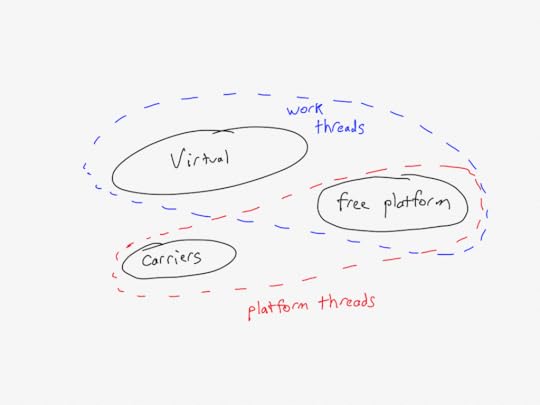

CONSTANTS VirtualThreads, CarrierThreads, FreePlatformThreadsVirtualThreads is the set of virtual threads that execute the application logic. CarrierThreads is the set of platform threads that will act as carriers for the virtual threads. To model the failure mode that was originally observed in the blog post, I also needed to have platform threads that will execute the application logic. I called these FreePlatformThreads, because these platform threads are never bound to virtual threads.

I called the threads that directly execute the application logic, whether virtual or (free) platform, “work threads”:

PlatformThreads == CarrierThreads \union FreePlatformThreadsWorkThreads == VirtualThreads \union FreePlatformThreadsHere’s a Venn diagram:

The state variables

The state variablesMy model has five variables:

VARIABLES pc, schedule, inSyncBlock, pinned, lockQueue TypeOk == /\ pc \in [WorkThreads -> {"ready", "to-enter-sync", "requested", "locked", "in-critical-section", "to-exit-sync", "done"}] /\ schedule \in [WorkThreads -> PlatformThreads \union {NULL}] /\ inSyncBlock \subseteq VirtualThreads /\ pinned \subseteq CarrierThreads /\ lockQueue \in Seq(WorkThreads)pc – program counter for each work thread schedule – function that describe how work threads are mounted to platform threadsinSyncBlock – the set of virtual threads that are currently inside a synchronized blockpinned – the set of carrier threads that are currently pinned to a virtual threadlockQueue – a queue of work threads that are currently waiting for the lockMy model only models a single lock, which I believe is this lock in the original scenario. Note that I don’t model the locks associated with the synchronization blocks, because there was no contention associated with those locks in the scenario I’m modeling: I’m only modeling synchronization for the pinning behavior.

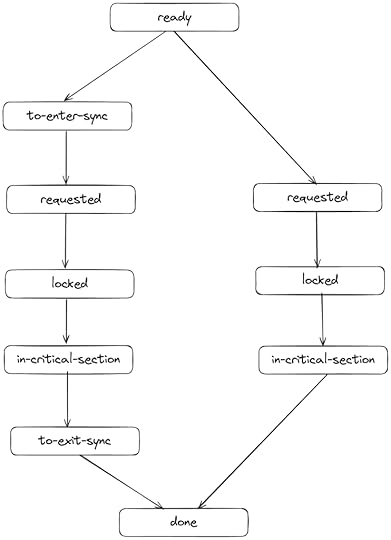

Program countersEach worker thread can take one of two execution paths through the code. Here’s a simplified view of the two different code possible paths: the left code path is when a thread enters a synchronized block before it tries to acquire the lock, and the right code path is when a thread does not enter a synchronized block before it tries to acquire the lock.

This is conceptually how my model works, but I modeled the left-hand path a little differently than this diagram. The program counters in my model actually transition back from “to-enter-sync” to “ready”, and they use a separate state variable (inSyncBlock) to determine whether to transition to the to-exit-sync state at the end. The other difference is that the program counters in my model also will jump directly from “ready” to “locked” if the lock is currently free. But showing those state transitions directly would make the above diagram harder to read.

The lockThe FIFO lock is modeled as a TLA+ sequence of work threads. Note that I don’t need to actually model whether the lock is held or not. My model just checks that the thread that wants to enter the critical section is at the head of the queue, and when it leaves the critical section, it gets removed from the head. The relevant actions look like this:

AcquireLock(thread) == /\ pc[thread] = "requested" /\ Head(lockQueue) = thread ...ReleaseLock(thread) == /\ pc[thread] = "in-critical-section" /\ lockQueue' = Tail(lockQueue) ...To check if a thread has the lock, I just check if it’s in a state that requires the lock:

\* A thread has the lock if it's in one of the pc that requires the lockHasTheLock(thread) == pc[thread] \in {"locked", "in-critical-section"}I also defined this invariant that I checked with TLC to ensure that only the thread at the head of the lock queue can be in any of these states.

HeadHasTheLock == \A t \in WorkThreads : HasTheLock(t) => t = Head(lockQueue)Pinning in synchronized blocksWhen a virtual thread enters a synchronized block, the corresponding carrier thread gets marked as pinned. When it leaves a synchronized block, it gets unmarked as pinned.

\* We only care about virtual threads entering synchronized blocksEnterSynchronizedBlock(virtual) == /\ pc[virtual] = "to-enter-sync" /\ pinned' = pinned \union {schedule[virtual]} ...ExitSynchronizedBlock(virtual) == /\ pc[virtual] = "to-exit-sync" /\ pinned' = pinned \ {schedule[virtual]}The schedulerMy model has an action named Mount that mounts a virtual thread to a carrier thread. In my model, this action can fire at any time, whereas in the actual implementation of virtual threads, I believe that thread scheduling only happens at blocking calls. Here’s what it looks like:

\* Mount a virtual thread to a carrier thread, bumping the other thread\* We can only do this when the carrier is not pinned, and when the virtual threads is not already pinned\* We need to unschedule the previous threadMount(virtual, carrier) == LET carrierInUse == \E t \in VirtualThreads : schedule[t] = carrier prev == CHOOSE t \in VirtualThreads : schedule[t] = carrier IN /\ carrier \notin pinned /\ \/ schedule[virtual] = NULL \/ schedule[virtual] \notin pinned \* If a virtual thread has the lock already, then don't pre-empt it. /\ carrierInUse => ~HasTheLock(prev) /\ schedule' = IF carrierInUse THEN [schedule EXCEPT ![virtual]=carrier, ![prev]=NULL] ELSE [schedule EXCEPT ![virtual]=carrier] /\ UNCHANGED <>My scheduler also won’t pre-empt a thread that is holding the lock. That’s because, in the original blog post, nobody was holding the lock during deadlock, and I wanted to reproduce that specific scenario. So, if a thread gets a lock, the scheduler won’t stop it from releasing the lock. And, yet, we can still get a deadlock!

Only executing while scheduledEvery action is only allowed to fire if the thread is scheduled. I implemented it like this:

IsScheduled(thread) == schedule[thread] # NULL\* Every action has this pattern:Action(thread) == /\ IsScheduled(thread) ....Finding the deadlockHere’s the config file I used to run a simulation. I had defined three virtual threads, two carrier threads, and one free platform threads.

INIT InitNEXT NextCONSTANTS NULL = NULL VirtualThreads = {V1, V2, V3} CarrierThreads = {C1, C2} FreePlatformThreads = {T1}CHECK_DEADLOCK TRUEINVARIANTS TypeOk MutualExclusion PlatformThreadsAreSelfScheduled VirtualThreadsCantShareCarriers HeadHasTheLockAnd, indeed, the model checker finds a deadlock! Here’s what the trace looks like in the Visual Studio Code plugin.

Note how virtual thread V2 is in the “requested” state according to its program counter, and V2 is at the head of the lockQueue, which means that it is able to take the lock, but the schedule shows “V2 :> NULL”, which means that the thread is not scheduled to run on any carrier threads.

And we can see in the “pinned” set that all of the carrier threads {C1,C2} are pinned. We also see that the threads V1 and V3 are behind V2 in the lock queue. They’re blocked waiting for the lock, and they’re holding on to the carrier threads, so V2 will never get a chance to execute.

There’s our deadlock!

You can find my complete model on GitHub at: https://github.com/lorin/virtual-threads-tla/