On writing and money (part one).

“It was so hard to be poor, not to have money and position, and to be able to do in life exactly as you wished.” – Theodore Dresier, An American Tragedy

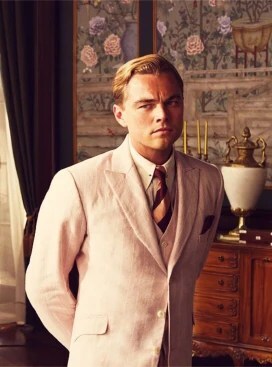

In my high school English classroom, the last novel we studied was the American classic (and my favorite novel of all time) The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. It is a timeless, powerful study of contemporary America and the ultimate denial of the American Dream for those working to achieve it. With that in mind, and based on the recommendation of actor Andrew McCarthy, I decided to read An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser: a sizable novel that was released at the same time as Fitzgerald’s novel and explores similar themes. What do these American classics communicate about the American Dream?

Jay Gatsby and Clyde Griffiths

Comparing the Characters

Comparing the CharactersJay Gatsby of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece The Great Gatsby and Clyde Griffiths, the protagonist of Dreiser’s novel An American Tragedy, are both considered to be victims “…of the contemporary American Dream” (Spindler 63). That is, the belief that in America, a person can be successful as long as they work hard. That belief “…is grounded in the production phase of American capitalism; moral value is placed upon a disciplined and abstemious life; and the existence of the class hierarchy is legitimated by a belief in predestination, adapted in such a way that economic success is taken as the confirmation of virtue, and failure, conversely, as the stigma of moral fault” (Spindler 68). In short, good people were successful and wealthy as evidence of their good moral character, since those less fortunate were slighted by whatever was lacking in their moral characters. Wealth and happiness go hand in hand: the richer someone is, the happier that person is. However, both characters are victims of a misplaced certainty in that American dream. Both characters personify the reality that money isn’t everything.

Jay Gatsby: Transcendentalist?Another American ideology that plays into that definition of the American Dream is Transcendentalism. It was the first major American philosophy, and it had four main tenants, but the most applicable to this discourse is that people are inherently good, the spiritual center of the universe. Fitzgerald seems to be more of a Transcendentalist, emphasizing that Gatsby’s greatest gift was his extraordinary gift for hope. Gatsby’s smile is also noted for how it makes the person seeing the smile feel rather than having anything to do with Gatsby himself. Gatsby gave to others in hopes that generosity would be returned, specifically in the affections of Daisy Buchanan. In essence, he really did do it all for love. In addition, in a touching scene before Gatsby’s funeral, Gatsby’s father shows Nick Gatsby’s schedule from when Gatsby was a young boy to show that he was indeed disciplined and not self-indulgent. To this end, Gatsby does not partake in the same vices his innumerable party guests did; he doesn’t drink or flirt or even dance. The only compliment narrator Nick Carraway ever pays Gatsby is that he’s “worth the whole damn bunch put together,” meaning that Gatsby stands out because he has an “incorruptible dream” and is not careless in the way the characters Tom and Daisy Buchanan are. Also, Gatsby is self-reliant and earns his wealth rather than inherits it. While this keeps him for being ingratiated into the “old money” social class, it does speak to the disciplined, abstemious nature that signals a worthiness of success. Unfortunately, his nature and good intentions are not enough to save him from a lonely, tragic fate: Gatsby is murdered and dies alone.

There is Something Darkly Romantic about Clyde GriffithsComparatively, Dreiser seems to be more influenced by the Dark Romanticism movement, which countered the optimism of Transcendentalism. Most prevalent in the works Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and focusing on darker spiritual truths, Dark Romanticism explored the human potential for evil. It also explored the psychological effects of sin and guilt. Clyde Griffiths is a perfect character study in that he lacks Gatsby’s moral fortitude. He is selfish and he suffers from a juvenile self-centeredness, a “fundamental flaw in Clyde’s character … Clyde had a soul that was not destined to grow up” (Spindler 67). He measures other characters only by what they can do for him and by what need they can fill for him. Clyde’s “…increasing reliance on a male version of the Cinderella myth, in which Sondra Finchley is cast as a Princess Charming who will spirit him into the ranks of the rich by marriage” (Spindler 69) is also evidence of his weak moral character. He is not necessarily willing to put in the work needed to earn wealth. He thumbs his nose at various jobs in the beginning of the novel, deciding to work as a bellboy at a luxury hotel for the optics of such a position, to be surrounded by wealth and luxury as if he can acquire it by osmosis. “Because Clyde lacks self-reliance and a willingness to put himself forward, he relies on ‘chance’ and ‘luck'” (Micklus 11). Clyde and Gatsby differ in their personalities in their levels of ambition, but the greater difference comes from their moral foundations.

Hit and Runs, Murder, and MoneyInterestingly, both novels feature a hit-and-run incident. Gatsby does not stop, but intends to take the blame for the death of Myrtle Wilson to protect Daisy Buchanan, the love of his life. His accumulation of wealth is really all for Daisy, to win her back and reclaim a better part of himself he attributes to loving her. In Clyde’s case, he is involved in a hit-and-run accident that kills a little girl. He is with a group of young people that “borrows” a car and is speeding to get it back. In their reckless speed, they run the girl down and do their best to evade the police. This results in them wrecking the car, and Clyde escapes on foot. He does not take accountability for his actions, nor does he is concerned with the wellbeing of his friends. This not only further illustrates Clyde’s moral shortcomings, but also foreshadows his violent attack on Roberta.

Roberta is from the same lower social class as Clyde and because he is somewhat spurned by his rich relatives upon arriving in Lycurgus, he is lonely. He ignores his uncle’s rule that supervisors can not enter into romantic relationships with the workers under their supervision, and he seduces Roberta. Because Clyde lacks “…any substantial core of self and the improbability of real growth” (Spindler 67), he does not take accountability for getting Roberta pregnant. When Roberta demands that he marry her and acknowledge the relationship, he murders Roberta and their unborn child. He wants to be with Sondra and live a life of luxury. Clyde is ultimately found out, tried in a court of law, convicted of the crime, and executed for his transgression.

Gatsby and Clyde both come to disastrous ends via different trajectories, but their origin stories are similar. Both long for the good life. “Clyde, born in the slums, of weak parents, romanticizes the idea of wealth, associates it with beautiful women, and longs for the life of riches and pleasure–which will always be beyond his grasp” (Lehan 187). Similarly, Gatsby runs away from his poor, shiftless parents to reinvent himself. Both come close to realizing their dreams but fall short because of their status of “outsider.” This is emphasized in both works, by the difference between “…the eastern Griffithses and the Finchleys with their power and affluence derived from the ownership of capital” and “…the western Griffithses and Aldens, owners of practically nothing, with their impotence and penury” (Spindler 64), just like the difference between the more fashionable, old monied East Egg and gaudy, distasteful West Egg. The wealthy are morally and physically separated from the impoverished. Undaunted by this way of the world, Clyde shares Gatsby’s desire to move between the locations and the social classes they represent. “Born of the one class, Clyde longs to be of the other, and An American Tragedy is essentially the story of his attempt and failure to cross the great divide” (Spindler 64). And that desire becomes incarnate in romantic inclinations. Like Gatsby, Clyde “…observes that it requires an expensive style of dress and hence a certain amount of money to win girls….” (Spindler 64). Much like Gatsby who learned what he could from his mentor Dan Cody to masquerade in desirable social circles, “Imitation is [Clyde’s] key mode of development” (Spindler 66). Both characters know how to play the part of a wealthy bachelor, but both characters lack the money to validate the image.

Both characters also fail to recognize the emptiness of the luxury they so ardently yearn for. “Clyde lives in a world he does not understand…. …in reality is ostentatious and gaudy wealth” (Lehan 187-8). Gatsby and Clyde are misguided because they conflate love and happiness with wealth and material goods. Both Clyde and Gatsby become victims of the American Dream turned American Nightmare. “Therein lies the tragedy: even when given a second chance, men–perhaps because they are men–will only repeat their failure” (Micklus 14). Gatsby admits that he could still be a great man if he could only forget he ever loved Daisy Buchanan. He tries to repeat the past and even when he has Daisy in his arms in his colossal mansion, it is not enough — he is not satisfied. Though Clyde does not want to repeat any part of his past and is constantly running from it, he does not learn from it. He continues to be selfish and cruel.

ConclusionMoney does not save either of character from a tragic end. America has certainly changed in the last century, but the idea that money can not buy true happiness persists. America is still a capitalist society where money is king, but it is openly acknowledged that chasing wealth is not the way to live.

So what does that mean for me, a struggling writer? I’ll put it all together in next week’s post.

The post On writing and money (part one). appeared first on mandi bean: writer.