“I Don’t Know if God is the Devil or the Devil is God.”

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The lectionary this Sunday excises from 2 Samuel 6 the story of the Lord striking Uzzah dead merely for touching the ark of the covenant.

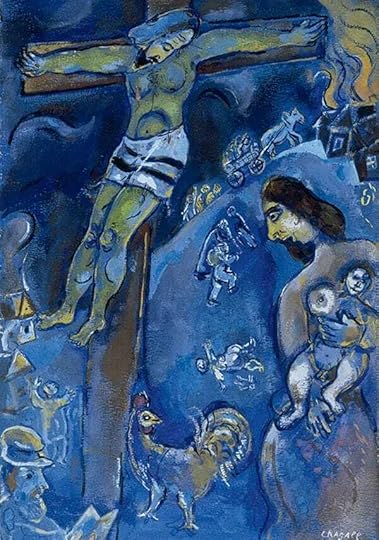

Rather than protect the church from the God of this passage, the church should instead point to the God who clothes himself in Christ. That is, the story of Uzzah’s unfortunate demise gets to the heart of Luther’s distinction between the Unpreached God and the Preached God.

My friend Ken Jones has a relevant passage on Luther’s distinction from his wonderful book.

The problem with philosophical proofs for God is that once you get yourself a provable God, it leaves way bigger questions standing there: If this God exists, how do you know who that God is? Is this God actually good? In the end, what will God’s judgment on you be?

All the questions and proofs force a difficult realization on you: using your senses and your rational mind, you can’t truly know anything about God’s existence, actions, or attitudes toward you.

And you wind up with my Twin Bed Theological Terrors.

If you try to suss it out by looking at the world around you, you might say you have found evidence in nature. The breathtaking beauty of a sunset, a rainbow, the variety of snowflakes and human faces, and the way harmony works in music—all these things show us both God’s existence and his goodness. You can add plenty more to the list from your own experience, from the taste of ripe strawberries, to rumbling thunder, to the twinkling of a field of stars on a summer’s night or that of your beloved’s eyes. Yet it is not hard to find other scientific explanations for all these things that say nothing at all about God.

What’s more, if you want to use beautiful and amazing things as proof of God’s existence or goodness, you also have to take with them all the bad things you see and experience in nature: natural disasters, cancer, the perils of toilet training, adolescent angst, and all those things insurance companies call “acts of God.”

Even if you could argue for God’s existence, when you add these things to the mix, it becomes hard to say whether God is even good. Luther said this was the greatest temptation.

Like Luther, you can get to the point where you say you “don’t know if God is the devil or the devil is God.”And in our game of divine Sardines, God remains tucked away in some inaccessible eternal nook. That is the exact confusion that crops up in the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 3. The temptation the serpent sets before the woman is not whether she and the man should eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Instead, the serpent asks whether they can trust God’s motives in commanding them to keep away from the tree and God’s judgment of death. The serpent says, “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:4b–5).

Instead of trusting God to give them all that they needed for their creaturely existence, they turned to the serpent for its wisdom and to themselves as agents for concocting their future. They came to think that God was holding back something especially good. At best, they regarded God as their lackey and, at worst, their enemy. Thus our first parents and every generation after them have taken matters into their own hands. That’s what happens when God remains hidden behind the veil, when you can’t grasp what God is up to, and when the threats and temptations of this world move you to seek certainty. You scramble to cobble together something sure.

Luther knew something of such things when he wrote his explanation of the first article of the Apostles’ Creed in the Small Catechism in 1529:

I believe that God has created me together with all that exists. God has given me and still preserves my body and soul: eyes, ears, and all limbs and senses; reason and all mental faculties. In addition, God daily and abundantly provides shoes and clothing, food and drink, house and farm, spouse and children, fields, livestock, and all property—along with all the necessities and nourishment for this body and life. God protects me against all danger and shields and preserves me from all evil. And all this is done out of pure, fatherly, and divine goodness and mercy, without any merit or worthiness of mine at all!

This is nothing like the vast, terrifying power of a God who remains hidden. Luther came to know a God who is gracious, patient, and lavish in bestowing gifts. In fact, he argued that you could come to see God in creation, even in the hard facts of life and the terror of nature’s perils.

You could come to regard all these things as simple masks covering the face of God.In the Old Testament, seeing God without a mask is a dangerous thing.When Moses and God’s people were enslaved in Egypt and Pharaoh finally released them from bondage, they stood trapped at the sea with the Egyptian armies, with all their horses and charioteers, coming up behind them. God appeared behind the masks of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. But when God gave the enemy armies a glimpse of divine might and glory, they were thrown into a panic. Their chariots were stuck, and people fled hither and yon—all from a wee glimpse behind the veil.

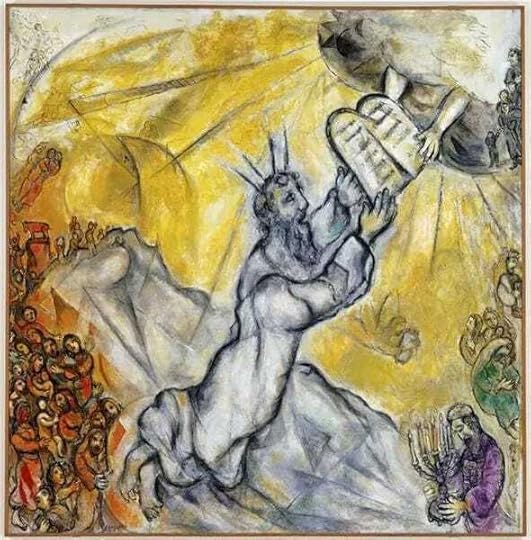

Later, when Moses was given the commandments on Mount Sinai, the mountain was clouded over, and the people below were protected from God’s nearness. When Moses said to God, “Show me your glory,” God said to Moses, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live” (Exodus 33:18–20). Moses was instructed to hide in a crack in the face of the rock, and Moses had to wait until God said “when.” The most Moses was allowed to see was God’s back, but still, when he came down from the mountain, Moses had been physically changed: “The skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God” (Exodus 34:29).

Looking at the guy who had looked at God so spooked the Israelites that from that time forward, Moses took the clouded Mount Sinai as his model: he wore a veil over his head and only took it off when he went back to the summit to chat with the Lord.

The commandment-inscribed tablets that God gave Moses were placed in a golden ark, which was carried with the Israelites in their wilderness wanderings and in their conquest of the land God had promised them. The ark that contained these tablets that God’s own hand had touched was so holy and so dangerous that when the Israelites moved their encampment, only the priests could come close, and the rest of the people were instructed to stay 1,000 yards away from it (Joshua 3:4). Years later, when the ark was being moved on an oxcart, the holy crate began to slip. A man named Uzzah reached out to steady it, and—Zap! Learn your lesson, Uzzah!—he was struck dead on the spot. King David heard of these things and was afraid to have the ark anywhere near him (1 Chronicles 13:9–14). When the temple was finally built in Jerusalem, the ark was installed in a space with floor-to- ceiling curtains surrounding it. The space was called the Holy of Holies, another way of saying it was the holiest of spaces. Ever. No one was allowed to enter except the high priest, and he could only do it on the Day of Atonement.

In the 1981 Steven Spielberg blockbuster, Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazi villains and the hero, Indiana Jones, are on a race to capture the Ark of the Covenant. The Nazis hope to harness its powers and use God as a weapon for Hitler and the Third Reich. At the climax of the movie, Indy and his companion Marion are themselves captured and bound while the Nazis intone the ancient words of the Israelite priests. As the villains lift the lid of the ark, Indy says, “Shut your eyes, Marion. Don’t look at it, no matter what happens.” The villains come to their end when the power and glory of God rise out of the ark and cause wholesale destruction: lightning-fried soldiers, melting faces, and exploding Nazi heads. But the protagonists are saved because they didn’t look or come near.

Of course, Raiders is a fiction, but in at least one way, it tells the truth.

Be careful about wanting to see an unhidden God.Even encountering God secondhand is dangerous stuff, and God will brook no attempts to get behind the veil. You won’t get to crawl into God’s hiding space and have other seekers cram in with you. The game of divine Sardines can’t end. You’re left to wander, grumpy and frustrated, and wonder what kind of God this is. You’ll say, “Hidden God? No thanks. I’ll stick with something I can see and trust.” And that’s where Article I of the Augsburg Confession is in your corner. By including the language of the Holy Trinity (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), Philip Melanchthon points to the places God wants to be encountered and where faith can actually see God. And it gets even more specific. The article speaks of who Jesus is: both completely divine and wholly human.

That means that in this person, Jesus of Nazareth, you have access to a God who is overflowing with loving kindness for broken and sinful human creatures.It means that God has determined to call everyone in from hiding, “Olly olly oxen free.” Or as Paul said in Galatians, “For freedom Christ has set us free”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers