Towards a Welsh Anglican Theology: Exploring the heart of the Church in Wales

The following is a shortened, popular version of an article that I am hoping to publish in an academic journal in due course. I gave talks on this at St Padarn’s Institute, Cardiff and at the South Wales Festival of Prayer and numerous people asked for a copy of the manuscript at the events or on social media, so I decided to publish this truncated version as a blogpost.

While the Church in Wales is facing an increasingly secularised society and falling attendance numbers, the impact it has had on the Welsh spiritual, cultural, and political landscape cannot be disparaged. At the heart of this contribution is a distinct theology and spirituality that is rarely noted. The presence of a specific Welsh Anglican theology may seem surprising in light of the fact that the Church in Wales is, quite literally, a broad church. Its congregations encompass a wide range of different ecclesial, theological and ethical viewpoints – from high church to evangelical, traditional to charismatic, liberal to conservative. Since its establishment a century ago, though, there has been, across these traditions, a move to liberate the Church from its old, anglicised image in order to embrace a new identity as a national Church, rooted in its Celtic past. This has allowed its theologians, poets, and writers to embrace certain theological threads and concepts that continue to drive Welsh Anglicans today and inspire the culture and politics of Wales.

There are two interrelated concepts energising Welsh Anglican theology and spirituality over the past century. They echo through Welsh theology generally, with nonconformist and Roman Catholic theologians and writers also tending towards these themes. And, albeit sometimes in secularised forms, they are also reflected in Welsh society, from its Celtic past through to its devolved political present. It is, though, in Welsh Anglicanism they have found a full and dynamic form over the past century and longer. These two interconnected theological concepts are sacrament and incarnation.

Sacrament (God in the everyday)Traditionally, the western Church has claimed there are a certain number of sacraments – for example, the Roman Catholic Church teaches there are seven sacraments. These are moments when God’s grace is imparted and his hope is revealed – so, for example, in holy communion or in baptism. But some theologians have suggested that all of creation is potentially sacramental. In other words, there is a “sacramental principle” at work in the world, as John MacQuarrie puts it, where creation reveals the power and beauty of God. During the past century, Welsh poetry, prose, and theology has tended towards such a notion. Perhaps at the root of this is the deep well of Celtic spirituality that we have inherited. While we need to be careful not to project whatever we want on the so-called Celtic Church, there is definitely a connection between Celtic Christianity and the Church in Wales today and this reveals an important element at the core of our Welsh Anglican way of being.

The ancient British texts paint a vivid picture of early Celtic Welsh Christians interacting with the God of the birds, animals and trees, while they lived as hermits on remote islands, faced demons on the top of mountains, and even prayed naked in freezing rivers. The Celtic attitude to nature reflected a desire to show that creation did not flow from pagan gods, but rather from the God of the Christian faith. Early Welsh Celtic Christianity was a faith that affirmed an immanent and sacramental God, as close and present as the natural world.

Rather than reflecting a future eschatology that was prominent in the Christian world down the centuries, this is far more reminiscent of realised eschatology, which became popular in the early twentieth century. Perhaps it is not such a coincidence that the principal proponent of realized eschatology was a Welsh biblical scholar, C. H. Dodd (1884–1973). Dodd suggested that the eschatological passages in the New Testament do not refer to the future, but instead refer to Jesus’s ministry and legacy. In other words, for Jesus, the kingdom of God is situated in the present – the kingdom is ushered in now through Jesus.

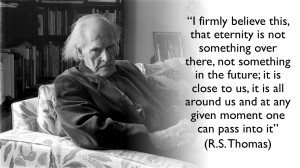

Welsh poet R.S. Thomas directly relates his faith to such a realised eschatological framework, referring to how his poetry attempts to give voice to experiences of the Kingdom of God breaking into the ordinariness of our lives. He wrote: “I firmly believe this, that eternity is not something over there, not something in the future; it is close to us, it is all around us and at any given moment one can pass into it”. We see this in his famous poem ‘The Bright Field’ (the moment of awe and wonder when you see the sun breaks through to illuminate a small field “is the eternity that awaits you”), and in his poem The Moor, when he experiences an intense communion with nature while walking on his local Welsh moorland – here he discovers a different church and an unusual eucharistic sacrament.

For the Welsh, then, the holiness of nature and of specific places may have started with the early Welsh Christians, but it has continued to today. George MacLeod, the Scottish minister who restored the monastery on Iona in 1938, coined the phrase “thin places” to describe these places where earth and heaven seem to touch and the membrane between this world and the next seems slight. In Wales we have ancient holy wells, wonderful majestic Cathedrals, pre-Christian megaliths, beautiful, isolated chapels and churches, imposing venerable trees, and awe-inspiring cliffs and mountains. God’s glory is written on every part of his creation, but in some places he writes in capital letters. Perhaps this is one reason why “place” has become central to most Welsh people today, whether they are Christian or not. I’ve heard it said that there is one fundamental difference between the English and Welsh – the first question an English person asks a stranger is “what do you do?”, whereas the first question a Welsh person asks a stranger is “where are you from?”

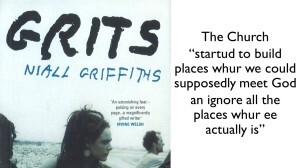

So, place is essential to the Welsh identity and certain, special places engender a sense of awe and sanctity in us. In Niall Griffiths’s novel Grits (2000), set in Aberystwyth in mid Wales, the character Liam claims that, in its early days, the church “startud to build places whur we could supposedly meet God an ignore all the places whur ee actually is”. Like an early Welsh saint, Liam, while walking on the beautiful Tan y Bwlch beach (near Aberystwyth), announces that God is to be found “in places like this, wild places, beaches an forests an mountains an lakes”.

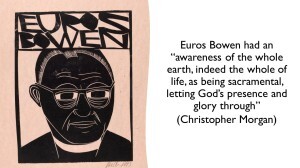

But a truly sacramental view of the world does not simply recognise the beauty and wonder of nature and place. Welsh poets Euros Bowen and RS Thomas even take the sacramental presence of God into the pains of the world. If religion is to speak to the world, then our faith should not only be concerned with breathtaking beauty, but must have something very real to say to the raw physicality of our daily lives – to the muck and the mud, to the dirt and the despair, to the suffering and the struggle:

“We must dip belief

Not in dew nor in the cool fountain

Of beech buds, but in seas

Of manure through which they squelch

To the bleakness of their assignations.” (R.S. Thomas, from ‘Not that he brought flowers’)

“I have seen summer decay

as an acorn rolls golden

into the shadow of the country’s oak,

like the smile of the departed

before burial in the earth. –

Life does not die. This is praise.” (Euros Bowen, ‘This is praise’ – translated by the poet)

And so, as Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann suggests, the whole of the world becomes “the primary sacrament”, with both its joys and misery becoming symbols for God’s glory and God’s hope. Schmemann even posited the idea of finding God in “hideous disasters”. This seems almost perverse. But here he is touching upon the importance of recognising that God is present in even our darkest moments. In a powerful article, written in response to the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, Rowan Williams points to the feelings of heartbreak during the 1966 Aberfan disaster, when 116 children and 28 adults died after the catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip. In many ways, the response of the Church to that horror typified what Williams puts forward as the only truly Christian response to suffering. There was, after all, a very practical and compassionate response in Aberfan from the churches and chapels. Having himself lost a child, Bishop Glyn Simon of Llandaff immediately cleared his diary and visited every bereaved home to drink tea and sit with the heartbroken parents.

It is the countless, small, seemingly-insignificant sacramental actions of Christians that Grahame Davies sees God’s Spirit working in today’s Wales. In his poem ‘Prayer’, he recognises that heroic acts and supernatural events don’t happen often, because these are not the moments where God most frequently chooses to reveal himself. Rather, it is in “mundane miracles”, “quiet words”, and “unnoticed acts” where God’s kingdom brought into being and his world is kept “moving slowly closer to the light”. The poem echoes the famous final words of Wales’s patron saint, St David: “Gwnewch y pethau bychain mewn bywyd” (“Do the little things in life”).

The recognition that God is present in everyday moments, awe-inspiring places, and compassionate actions continues to inspire Welsh Christians today. The Church in Wales champions a ministry of presence and action in both the joy and the pains of our twenty-first-century world. In churches across Wales, the glimmers of his light shine all around us today. By noticing those signs of wonder, hope, and compassion now, we somehow touch the not yet of the glorious future kingdom.

Incarnation (God in the other)The incarnation is at the very heart of the Christian faith. The idea that God became human in the person of Jesus Christ has profound implications on our spirituality and on our everyday lives. The incarnation mandates that we not only become Christ to others, but that we see Christ in others. Jesus stated that when we respond to the needs of others, we are responding to Christ’s own needs; and when we ignore their needs, we are ignoring him: ‘truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me’ (Matthew 25:40). Our lives must be a process of recognizing Christ in others, and especially those who are suffering.

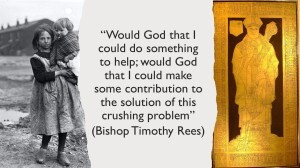

The truly incarnational faith of Welsh Anglicanism brings Christ down to the mud and the blood of this often-cruel world. In his famous hymn ‘God is love, let heaven adore him’, Bishop Timothy Rees of Llandaff, suggested that “when human hearts are breaking under sorrow’s iron rod, then we find that self-same aching deep within the heart of God”. Bishop Rees himself lived this compassionate, incarnational vision, as he faced the heartbreaking unemployment, economic depression, and social upheaval of the interwar years in Wales. His practical care included him opening Bishop’s Palace in Llandaff to parties of unemployed, while his drive for social justice led him to put pressure on politicians and industrial leaders. He even led a deputation to Whitehall in 1935 to plead for the government help for the rejuvenation of South Wales. “Would God that I could do something to help;” he said, “would God that I could make some contribution to the solution of this crushing problem”.

Other Welsh poets and theologians have reflected this incarnational outlook. It was sharply caught by Gwenallt Jones when he wrote in the poem ‘Trychineb Aber-fan’ that “the sludge of Tip Seven turned Aberfan like Bethlehem and Ramah”, while RS Thomas’s poems described the raw and uncompromising sacrificial obligations of the incarnation – “the holly will remind us how love bleeds” he wrote in the poem ‘Festival’.

Likewise, Manon Ceridwen James, in her poem ‘Advent’ reminds us that self-awareness and self-reflection are integral to a truly incarnational view of the suffering other. This poem modernises Matthew 25, with its title emphasising the incarnational foundation further (“Advent”) – we are not waiting for the Christ child anymore, because he is with us in the form of prisoners, alcoholics, the homeless, the sick, the poor, children, and the hungry. James reminds us of the current temptation to assign blame and look for excuses in reaching out to those who are marginalised in our society. There are, after all, always reasons to ignore the incarnated Jesus in our communities or to treat him with less regard than yourself:

“I was hungry

and you said, here, you can have this tin for your foodbank.

It’s out of date anyway.”

But the incarnation is not just about the oppressed and marginalised. The prologue of John’s Gospel reveals Christ transcends mere human issues. God is, after all, concerned with the entire cosmos, which he continually creates and sustains (see Colossians 1.17, Romans 8.22, and Ephesians 1.10). “Christ, through his incarnation,” wrote Teilhard de Chardin, “is internal to the world, rooted in the world, even in the very heart of the tiniest atom”. This is radical incarnationalism, where we recognize that Jesus is not just in everyone, he is in everything. This has particular relevance to us in the twenty-first century, as we face unprecedented threats to the environment. If we recognize that the incarnation reaches out beyond humanity alone and that Christ is truly present in the living world around us, then we surely should be inspired to make bolder moves towards healing our fragile world.

This Universal Christ of radical incarnationalism is found, sometimes subtly and sometimes tangibly, in Welsh Anglican thinking down the years. It relates closely, of course, both to the emphasis on nature in Welsh Celtic spirituality and to the “sacramental principle” of Welsh Anglican theology. As Mark Clavier, Canon Theologian at Brecon Cathedral, reflected on a hike on the Eryri peak Cadair Idris: “call this sacramental or incarnational, it reminds us that God and creation are not opposed, that our spirit and body should enjoy a nuptial love, and that the fact that God became man explains all”. Likewise, in one of his most famous poems, ‘The Bright Field’, R.S. Thomas describes a spiritual hiraeth, a sense of separation that leads to a profound longing. This again reflects the “now” and the “not yet” of the kingdom. The “pearl of great price” and “the treasure” of the parables that we should all be striving for is the noticing of the universal Christ all around us.

Conclusion

So, sacrament and incarnation have become the interrelated twin foundations stones of Welsh Anglican spirituality. Both have roots in ancient Celtic spirituality, but also they are reflected in contemporary Welsh secular thinking. Following the devolution referendum of 1997, politicians put together the Government of Wales Act of 1998. With its emphasis on the “duty to promote sustainable development”, Wales, rooted in its Celtic Christian past, became the first country in the western world to have a duty to environmental care explicitly stated in its founding constitution. Furthermore, seventeen years later, with the groundbreaking Well-being of Future Generations Act of 2015, Wales became the only country in the world to place sustainable practice, alongside compassion and care for the disadvantaged, at the heart of government and to embed in law the protection of future generations.

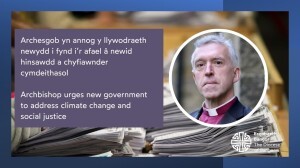

It is, of course, a matter of debate whether the work and witness of our Welsh Anglican thinkers had a great influence on these policies that, for Christians, echo sacrament and incarnation. What is certain, though, is that Church in Wales spirituality continues to drive for social and environmental change, not least through its leaders. Archbishop Barry Morgan was pivotal in the successful move towards law-making powers for the devolved Welsh Government, while Archbishop Rowan Williams, on returning to Wales from Canterbury, accepted various high-profile roles within the political and social life of Wales. It was, therefore, no surprise that, after the 2024 UK General Election, Archbishop Andrew John announced on social media that he hoped the new government would address two things – climate change (sacrament) and social justice (incarnation).

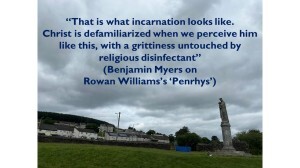

It is perhaps Rowan Williams’s poem ‘Penrhys’ that most viscerally embodies the raw incarnationalism and compassionate sacramentalism of the Welsh tradition. In the poem both the Celtic connection with place and people (sacrament) and the call to care for the marginalised and oppressed (incarnation) is shown to be still very much alive in Welsh Anglicanism. Williams contrasts the sacredness of the medieval shrine of Penrhys in the South Wales Rhondda valley with its present predicament as one of the most disadvantaged housing developments in Wales. So, it is precisely here, in the post-industrial squalid surroundings (“broken glass… turds are floating in the well… cartons and condoms”), that Williams finds the hope of the incarnation (in the “thin teenage mothers by the bus stop”). After all, it is in the destitute housing estates across Wales, just as much as in its grand cathedrals, that God’s kingdom is breaking through. The Penrhys council estate has been transformed in recent years by the faithful and constant love of a church community, with its vibrant partnerships with political, social, and charitable bodies. With this in mind, both the poem and the place reflect the continuing power, tenacity, and persistence of Welsh Anglican spirituality to stimulate and impact both urban and rural areas across the nation in inspirational and practical ways.