Dirty writes

For databases that support transactions, there are different types of anomalies that can potentially occur: the higher the isolation level, the more classes of anomalies are eliminated (at a cost of reduced performance).

The anomaly that I always had the hardest time wrapping my head around was the one called a dirty write. This blog post is just to provide a specific example of a dirty write scenario and why it can be problematic. (For another example, see Adrian Coyler’s post).

Here’s how a dirty write is defined in the paper A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels:

Transaction T1 modifies a data item. Another transaction T2 then further modifies that data item before T1 performs a COMMIT or ROLLBACK.

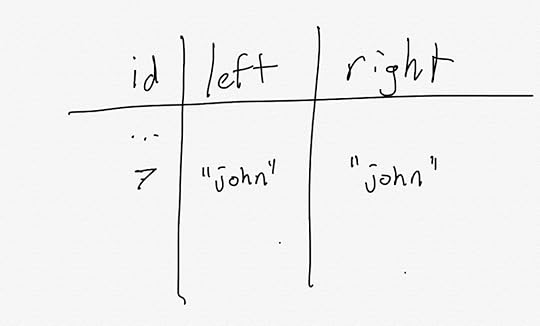

Here’s an example. Imagine a bowling alley has a database where they keep track of who has checked out a pair of bowling shoes. For historical reasons, they track the left shoe borrower and the right shoe borrower as separate columns in the database:

Once upon a time, they used to let different people check out the left and the right shoe for a given pair. However, they don’t do that anymore: now both shoes must always be checked out by the same person. This is the invariant that must always be preserved in the database.

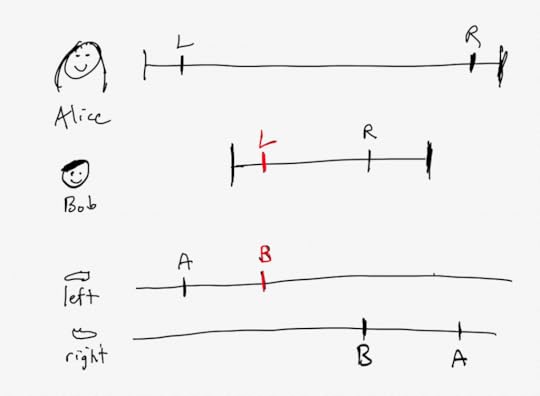

Consider the following two transactions, where both Alice and Bob are trying to borrow the pair of shoes with id=7.

-- Alice takes the id=7 pair of shoesBEGIN TRANSACTION;UPDATE shoes SET left = "alice" WHERE id=7;UPDATE shoes SET right= "alice" WHERE id=7;COMMIT TRANSACTION;-- Bob takes the id=7 pair of shoesBEGIN TRANSACTION;UPDATE shoes SET left = "bob" WHERE id=7;UPDATE shoes SET right= "bob" WHERE id=7;COMMIT TRANSACTION;Let’s assume that these two transactions run concurrently. We don’t care about whether Alice or Bob is the one who gets the shoes in the end, as long as the invariant is preserved (both left and right shoes are associated with the same person once the transactions complete).

Now imagine that the operations in these transactions happen to be scheduled so that the individual updates and commits end up running in this order:

SET left = “alice”SET left = “bob”SET right = “bob”Commit Bob’s transactionSET right = “alice”Commit Alice’s transactionsI’ve drawn that visually here, where the top part of the diagram shows the operations grouped by Alice/Bob, and the bottom part shows them grouped by left/right column writes.

If the writes actually occur in this order, then the resulting table column will be:

idleftright7“bob”“alice”Row 7 after the two transactions completeAfter these transactions complete, this row violates our invariant! The dirty write is indicated in red: Bob’s write has clobbered Alice’s write.

Note that dirty writes don’t require any reads to occur during the transactions, nor are they only problematic for rollbacks.