Modeling B-trees in TLA+

I’ve been reading Alex Petrov’s Database Internals to learn more about how databases are implemented. One of the topics covered in the book is a data structure known as the B-tree. Relational databases like Postgres, MySQL, and sqlite use B-trees as the data structure for storing the data on disk.

I was reading along with the book as Petrov explained how B-trees work, and nodding my head. But there’s a difference between feeling like you understand something (what the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen calls clarity) and actually understanding it. So I decided to model B-trees using TLA+ as an exercise in understanding it better.

TLA+ is traditionally used for modeling concurrent systems: Leslie Lamport originally developed it to help him reason about the correctness of concurrent algorithms. However, TLA+ works just fine for sequential algorithms as well, and I’m going to use it here to model sequential operations on B-trees.

What should it do? Modeling a key-value storeBefore I model the B-tree itself, I wanted to create a description of its input/output behavior. Here I’m going to use B-trees to implement a key-value store, where the key must be unique, and the key type must be sortable.

The key-value store will have four operations:

Get a value by key (key must be present)Insert a new key-value pair (key must not be present)Update the value of an existing pair (key must be present)Delete a key-value pair by key. (It is safe to delete a key that already exists).In traditional programming languages, you can define interfaces with signatures where you specify the types of the input and the types of the output for each signature. For example, here’s how we can specify an interface for the key-value store in Java.

interface KVStore,V> { V get(K key) throws MissingKeyException; void insert(K key, V val) throws DuplicateKeyException; void update(K key, V val) throws MissingKeyException; void delete(K key);}However, Java interfaces are structural, not behavioral: they constrain the shape of the inputs and outputs. What we want is to fully specify what the outputs are based on the history of all previous calls to the interface. Let’s do that in TLA+.

Note that TLA+ has no built-in concept of a function call. If you want to model a function call, you have to decide on your own how you want to model it, using the TLA+ building blocks of variables.

I’m going to model function calls using three variables: op, args, and ret:

op – the name of the operation (function) to execute (e.g., get, insert, update, delete)args – a sequence (list) of arguments to pass to the functionret – the return value of the functionWe’ll model a function call by setting the op and args variables. We’ll also set the ret variable to a null-like value (I like to call this NIL).

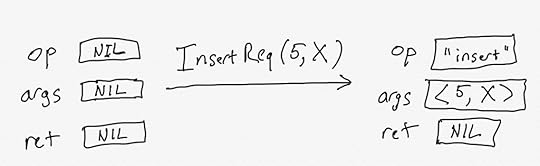

Modeling an insertion requestFor example, here’s how we’ll model making an “insert” call (I’m using ellipsis … to indicate that this isn’t the full definition), using a definition called InsertReq (the “Req” is short for request).

InsertReq(key, val) == /\ op' = "insert" /\ args' = <> /\ ret' = NIL /\ ...Here’s a graphical depiction of InsertReq, when passed the argument 5 for the key and X for the value. (assume X is a constant defined somewhere else).

The diagram above shows two different states. In the first state, op, args, and ret are all set to NIL. In the second state, the values of op and args have changed. In TLA+, a definition like InsertReq is called an action.

Modeling a response: tracking stores keys and valuesWe’re going to define an action that completes the insert operation, which I’ll call InsertResp. Before we do that, we need to cover some additional variables that we need to track. The op, args, ret model the inputs and outputs, but there are some additional internal state we need to track.

The insert function only succeeds when the key isn’t already present. This means we need to track which keys have been stored. We’re also going to need to track which values have been stored, since the get operation will need to retrieve those values.

I’m going to use a TLA+ function to model which keys have been inserted into the store, and their corresponding values. I’m going to call that function dict, for dictionary, since that’s effectively what it is.

I’m going to model this so that the function is defined for all possible keys, and if the key is not in the store, then I’ll use a special constant called MISSING.

We need to define the set of all possible keys and values as constants, as well as our special constant MISSING, and our other special constant, NIL.

This is also a good time to talk about how we need to initialize all of our variables. We use a definition called Init to define the initial values of all of the variables. We initialize op, args, and ret to NIL, and we initialize dict so that all of the keys map to the special value MISSING.

CONSTANTS Keys, Vals, MISSING, NILASSUME MISSING \notin ValsInit == /\ op = NIL /\ args = NIL /\ ret = NIL /\ dict = [k \in Keys |-> MISSING] /\ ...We can now define the InsertResp action, which updates the dict variable and the return variable.

I’ve also defined a couple of helpers called Present and Absent to check whether a key is present/absent in the store.

Present(key) == dict[key] \in ValsAbsent(key) == dict[key] = MISSINGInsertResp == LET key == args[1] val == args[2] IN /\ op = "insert" /\ dict' = IF Absent(key) THEN [dict EXCEPT ![key] = val] ELSE dict /\ ret' = IF Absent(key) THEN "ok" ELSE "error" /\ ...The TLA+ syntax around functions is a bit odd:

[dict EXCEPT ![key] = val]The above means “a function that is identical to dict, except that dict[key]=val“.

Here’s a diagram of a complete entire insert operation. I represented a function in my diagram as a set of ordered pairs, where I only explicitly show the one that changes in the diagram.

What action can come next?

What action can come next?As shown in the previous section, the TLA+ model I’ve written requires two state transitions to implement a function call. In addition, My model is sequential, which means that I’m not allowing a new function call to start until the previous one is completed. This means I need to track whether or not a function call is currently in progress.

I use a variable called state, which I set to “ready” when there are no function calls currently in progress. This means that we need to restriction actions that initiate a call, like InsertReq, to when the state is ready:

InsertReq(key, val) == /\ state = "ready" /\ op' = "insert" /\ args' = <> /\ ret' = NIL /\ state' = "working" /\ ...Similarly, we don’t want a response action like InsertResp to fire unless the corresponding request has fired first, so we need to ensure both the op and the state match what we expect:

Present(key) == dict[key] \in ValsAbsent(key) == dict[key] = MISSINGInsertResp == LET key == args[1] val == args[2] IN /\ op = "insert" /\ state = "working" /\ dict' = IF Absent(key) THEN [dict EXCEPT ![key] = val] ELSE dict /\ ret' = IF Absent(key) THEN "ok" ELSE "error" /\ state' = "ready"You can find the complete behavioral spec for my key-value store, kvstore.tla, on github.

Modeling a B-treeA B-tree is similar to a binary search tree, except that each non-leaf (inner) node has many children, not just two. In addition, the values of are only stored in the leaves, not in the inner nodes. (This is technically a B+ tree, but everyone just calls it a B-tree).

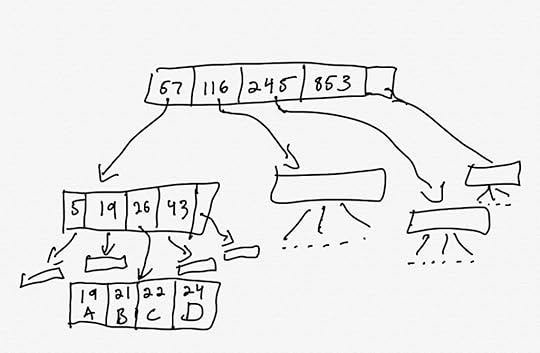

Here’s a diagram that shows part of a B-tree

There are two types of nodes, inner nodes and leaf nodes. The inner nodes hold keys and pointers to other nodes. The leaf nodes hold keys and values.

For an inner node, each key, k points to a tree that contains keys that are strictly less than k. In the example above, the node 57 at the root points to a tree that contains keys less than 57, the node 116 points to keys between 57 (inclusive) and 116 exclusive, and so on.

Each inner node also has an extra pointer, which points to a tree that contains keys larger than the largest key. In the example above, the root’s extra pointer points to a tree that contains keys greater than or equal to 853.

The leaf nodes contain key-value pairs. One leaf node is shown in the example above, where key 19 corresponds to value A, key 21 corresponds to value B, etc.

Modeling the nodes and relationsIf I was implementing a B-tree in a traditional programming language, I’d represent the nodes as structs. Now, while TLA+ does have structs, I didn’t use them for modeling a B tree. Instead, following Hillel Wayne’s decompose functions of structs tip, I used TLA+ functions instead.

(I actually started with trying to model it with structs, then I switched to functions, and then later found Hillel Wayne’s advice.)

I also chose to model the nodes and keys as natural numbers, so I could easily control the size of the model by specifying maximum values for keys and nodes. I didn’t really care about changing the size of the set of values as much, so I just modeled them as a set of model values.

In TLA+. that looks like this:

CONSTANTS Vals, MaxKey,MaxNode, ...Keys == 1..MaxKeyNodes == 1..MaxNodeHere are the functions I defined:

isLeaf[node] – true if a node is a leafkeysOf[node] – the set of keys associated with a node (works for both inner and leaf nodes)childOf[node, key] – given a node and a key, return the child node it points to (or NIL if it doesn’t point to one)lastOf[Node] – the extra pointer that an inner node points tovalOf[node, key] – the value associated with a key inside a leaf nodeI also had a separate variable for tracking the root, unimaginatively called root.

When modeling in TLA+, it’s helpful to define a type invariant. Here’s the relevant part of the type invariant for these functions.

TypeOk == /\ root \in Nodes /\ isLeaf \in [Nodes -> BOOLEAN] /\ keysOf \in [Nodes -> SUBSET Keys] /\ childOf \in [Nodes \X Keys -> Nodes \union {NIL}] /\ lastOf \in [Nodes -> Nodes \union {NIL}] /\ valOf \in [Nodes \X Keys -> Vals \union {NIL}] /\ ...Modeling insertsWhen inserting an element into a B-tree, you need to find which leaf it should go into. However, nodes are allocated a fixed amount of space, and as you add more data to a node, the amount of occupied space, known as occupancy, increases. Once the occupancy reaches a limit (max occupancy), then the node has to be split into two nodes, with half of the data copied into the second node.

When a node splits, its parent node needs a new entry to point to the new node. This increases the occupancy of the parent node. If the parent is at max occupancy, it needs to split as well. Splitting can potentially propagate all of the way up to the root. If the root splits, then a new root node needs to be created on top of it.

This means there are a lot of different cases we need to handle on insert:

Is the target leaf at maximum occupancy?If so, is its parent at maximum occupancy? (And on, and on)Is its parent pointer associated with a key, or is its parent pointer that extra (last) pointer?After the node splits, should the key/value pair be inserted into the original node, or the new one?In our kvstore model, the execution of an insertion was modeled in a single step. For modeling the insertion behavior, I used multiple steps. To accomplish this, I defined a state variable, that can take on the following values during insertion:

FIND_LEAF_TO_ADD – identify which leaf the key/value pair should be inserted inWHICH_TO_SPLIT – identify which nodes require splittingSPLIT_LEAF – split a leaf nodeSPLIT_INNER – split an inner nodeSPLIT_ROOT_LEAF – split the root (when it is a leaf node)SPLIT_ROOT_INNER – split the root (when it is an inner node)I also defined two new variables:

focus – stores the target leaf to add the data totoSplit – a sequence (list) of the nodes in the chain from the leaf upwards that are at max occupancy and so require splitting.I’ll show two of the actions, the one associated with FIND_LEAF_TO_ADD and WHICH_TO_SPLIT states.

FindLeafToAdd == LET key == args[1] leaf == FindLeafNode(root, key) IN /\ state = FIND_LEAF_TO_ADD /\ focus' = leaf /\ toSplit' = IF AtMaxOccupancy(leaf) THEN <> ELSE <<>> /\ state' = IF AtMaxOccupancy(leaf) THEN WHICH_TO_SPLIT ELSE ADD_TO_LEAF /\ UNCHANGED <>WhichToSplit == LET node == Head(toSplit) parent == ParentOf(node) splitParent == AtMaxOccupancy(parent) noMoreSplits == ~splitParent \* if the parent doesn't need splitting, we don't need to consider more nodes for splitting IN /\ state = WHICH_TO_SPLIT /\ toSplit' = CASE node = root -> toSplit [] splitParent -> <> \o toSplit [] OTHER -> toSplit /\ state' = CASE node # root /\ noMoreSplits /\ isLeaf[node] -> SPLIT_LEAF [] node # root /\ noMoreSplits /\ ~isLeaf[node] -> SPLIT_INNER [] node = root /\ isLeaf[node] -> SPLIT_ROOT_LEAF [] node = root /\ ~isLeaf[node] -> SPLIT_ROOT_INNER [] OTHER -> WHICH_TO_SPLIT /\ UNCHANGED <>You can see that the WhichToSplit action starts to get a bit hairy because of the different cases.

Allocating new nodesWhen implementing a B-tree, we need to dynamically allocate a new node when an existing node gets split, and when the root splits and we need a new root.

The way I modeled this was to through the concept of a free node. I modeled the set of Nodes as a constant, and I treated some nodes as part of the existing tree, and other nodes as free nodes. When I needed a new node, I used one of the free ones.

I could have defined an isFree function, but instead I considered a node to be free if it was a leaf (which all nodes are set at initialized to in Init) without any keys (since all leaves that are part of the tree.

\* We model a "free" (not yet part of the tree) node as one as a leaf with no keysIsFree(node) == isLeaf[node] /\ keysOf[node] = {}Sanity checking with invariantsI defined a few invariants to check that the btree specification was behaving as expected. These caught some errors in my model as I went along. I also had an invariant that checks if there are any free nodes left. If not, it meant I needed to increase the number of nodes in the model relative to the number of keys.

\*\* Invariants\*Inners == {n \in Nodes: ~isLeaf[n]}InnersMustHaveLast == \A n \in Inners : lastOf[n] # NILKeyOrderPreserved == \A n \in Inners : (\A k \in keysOf[n] : (\A kc \in keysOf[childOf[n, k]]: kc < k))LeavesCantHaveLast == \A n \in Leaves : lastOf[n] = NILKeysInLeavesAreUnique == \A n1, n2 \in Leaves : ((keysOf[n1] \intersect keysOf[n2]) # {}) => n1=n2FreeNodesRemain == \E n \in Nodes : IsFree(n)Partially complete model (no deletions)You can find the full model in the btree.tla file in the GitHub repo. Note that I didn’t get around to modeling deletions. I was happy with just get/insert/update, and I figured that it would be about as much work as modeling inserts, which was quite a bit.

Does our model match the behavioral spec?Recall that we stored by defining a behavioral specification for a key-value store. We can check that the B-Tree implements this behavioral specification by defining a refinement mapping.

My btree model uses many of the same variables as the kvstore model, but there are two exceptions:

the kvstore model has a dict variable (a function that maps keys to values) which the btree model doesn’t.Both models have a variable named state, but in the kvstore model this variable only take the values “ready” and “working”, whereas in the btree model it take on other values, because the btree model has finer-grained states.This means we need to define mappings from the variables in the btree model to the variables in the kvstore model. Here’s how I did it:

Mapping == INSTANCE kvstore WITH dict IF \E leaf \in Leaves : key \in keysOf[leaf] THEN LET leaf == CHOOSE leaf \in Leaves : key \in keysOf[leaf] IN valOf[leaf, key] ELSE MISSING], stateFor the other variables (op, args, ret), the default mapping works just fine.

We can then use the model checker (TLC) to check the Refinement property. I’m using the , which drives the model checker using config files. I added this to my btree.cfg to tell it to check the “Refinement” temporal property defined above.

PROPERTYRefinementBy doing this, the model checker will verify that:

every valid initial state for the btree model is also a valid initial state for the kvstore modelevery valid state transition for the btree model is also a valid state transition for the kvstore model.And, indeed, the model checker succeeds!

Hey, why did the model checker succeed when you didn’t implement delete?You’ll note that the original kvstore model handles a delete operation, but my btree model doesn’t. The reason that checking the refinement property didn’t pick up in this is that it’s valid behavior under the definition of the kvstore model for it to never actually call delete.

In the formal methods jargon, the btree spec does not violate any of the safety properties of the kvstore spec (i.e., the btree spec never makes a state transition that would be disallowed by the kvstore spec). But to check that btree implements the delete function, we need what’s called a liveness property.

We can define a liveness property by altering the kvstore model to require that delete operations be performed, by specifying fairness in our kvstore model.

Here’s the general form of a TLA+ specification, where you define an initial state predicate (Init) and a next-state predict (Next). It looks like this.

Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_varsFor the kvstore model, I added an additional fairness clause.

Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_vars /\ WF_op(\E k \in Keys: DeleteReq(k))Informally, that extra clause says, “if the model ever reaches a state where it can run a delete operation, it should eventually perform the operation”. (More formally, it says that: If the predicate \E k \in Keys: DeleteReq(k) becomes forever enabled, then there must be a step (state transition) where the op variable changes state.)

Effectively, it’s now part of the kvstore specification that it perform delete operations. When I then run the model checker, I get the error: “Temporal properties were violated.“

Choosing the grain of abstractionOne of the nice things about TLA+ is that you can choose how granular you want your model to be. For example, in my model, I assumed that both inner and leaf nodes had occupancy determined by the number of elements. In a real B-tree, that isn’t true. The data stored in the inner nodes is a list of (key, pointer) pairs, which are fixed size. But the actual values, the data stored, is variable size (for example, consider variable-sized database records like varchars and blobs).

Managing the storage is more complex within the leaves than in the inner nodes, and Petrov goes into quite a bit of detail on the structure of a B-tree leaf in his book. I chose not to model these details in my btree spec: The behavior of adding and deleting the data within a leaf node is complex enough that, if I were to model the internal behavior of leaves, I’d use a separate model that was specific to leaf behavior.

Formal modeling as a tool of thoughtI found this a useful exercise for understanding how B-trees work. It was also helpful to practice my TLA+ skills. TLA+ allows you to abstract away all of the details that you consider irrelevant. However, for whatever remains, you need to specify things exhaustively: precisely how every variable changes, in every possible transition. This can be tedious, but it also forces you to think through each case.

You can find the TLA+ files at github.com/lorin/btree-tla.