Digital Attention Spans: AI as a Source of Infinite Patience

I recently came across a Substack post by Venkatesh Rao called Oozy Intelligence in Slow Time that was one of the most insightful I’ve ever read for understanding the nature of Artificial Intelligence.

We tend to think of Artificial Intelligence as being in an arms race with Human Intelligence. Which one is smarter? When will AI surpass us?

But there is a hidden assumption buried in that comparison: that intelligence is best measured by its peak moments – the flash of brilliance, the sudden epiphany, the intellectual breakthrough.

Rao suggests that we look instead at a completely different aspect of intelligence: how much it costs.

Human intelligence is tremendously costly. Most of our time is spent simply maintaining this high-performance machine we call our body. Eating, drinking, sleeping, grooming, socializing, resting, etc. can all be seen as “overhead costs” needed to merely keep us alive.

Because it costs so much just to function each day, every minute of focused attention we spend requires a certain return-on-investment to be justified. We are constantly making choices to maximize that “return” on our attention: Do I spend the next 30 minutes working out, or cleaning the kitchen? Do I spend today working on this project, or that project?

Activities that don’t meet our threshold for “required return” don’t get our attention, plain and simple. This can be understood as a kind of “minimum wage” that our brain must earn, otherwise it refuses to work.

We make this calculation fairly seamlessly any time we consider engaging in an activity:

We might be willing to spend 10 minutes reading an interesting article, but not if it takes 30 minutes (“too long, didn’t read”).We might be willing to drive 20 minutes to eat at an exciting new restaurant, but not if it takes an hour.If you buy an appliance for your home that costs $20, but you spent 2 hours reading reviews and evaluating the options, the return on that purchase is lower than if you had instead received and acted on a trusted recommendation from a friendThis is part of what makes learning anything new so challenging: you have to spend lots and lots of time, with little return on that investment, in order to gain some future reward that isn’t even guaranteed. It’s akin to investing a lot of money into something without knowing if it will ever pay you back.

Another way of defining the “minimum wage threshold” for our brains is patience.

Rao asks: “How often are you in the mood to do boring, tedious, bureaucratic tasks (such as filling out forms, doing your taxes, or opening postal mail)?”

His answer, and mine, is: not often. It’s not that I don’t have the time for such tasks. It’s not that I’m not smart enough or don’t know how to complete them. The problem is that they require too much patience (i.e. they fail to meet my brain’s minimum wage threshold). I thus “can’t afford” to spend my attention on them, and instead tend to put them off for as long as humanly possible, usually until some catastrophic consequence becomes threatening enough that I have no choice.

If you think about it, there are many such tasks that would produce immense benefits for us, if we just had the patience to do them:

Spending hundreds of hours learning a new language or how to codeReviewing every note you’ve taken over the last few years for buried ideas or insightsOrganizing all your personal contacts in a searchable Notion databaseThese kinds of tasks involving collecting, organizing, summarizing, formatting, and reviewing information would be tremendously valuable if we did them, but often fall into the “requires too much patience” category for most people.

This is where AI becomes so powerful. AI effectively lowers the patience threshold to almost nothing. There is no task that is too boring, too mundane, too repetitive, or “beneath its dignity.” Unlike us, grinding away on such tasks doesn’t annoy it, ruin its motivation, give it a bad attitude, or make it angry at us. It is a dutiful employee requiring a minimum wage of virtually zero.

This is a very different way of understanding AI’s value. It’s not AI’s superintelligence or blazing speed that make it valuable to us: it’s AI’s patience in completing an endless series of tedious tasks that are too far below our patience threshold for us to justify doing at all.

Our attention is expensive, and thus can only be spent on activities with a clear outcome that can be achieved in a predictable amount of time. Whereas AI has an almost infinite amount of attention that is so cheap it can be spent lavishly, even wastefully, on activities that would never be worth our time. We can afford to spend this newly abundant form of intelligence on tasks that are below the minimum wage our brains are willing to work for.

If we stopped here, this would mean that the main use for AI is completing our boring to-do lists for us. But there’s a level deeper to consider, because patience has two components that can be separated: time and detail.

As you toil away filing your taxes, for example, there are two factors that determine how much patience it takes: the level of detail that you’re required to process and the time it takes to do so. It is the combination of many complex details you have to process over a long span of time that makes taxes so excruciating.

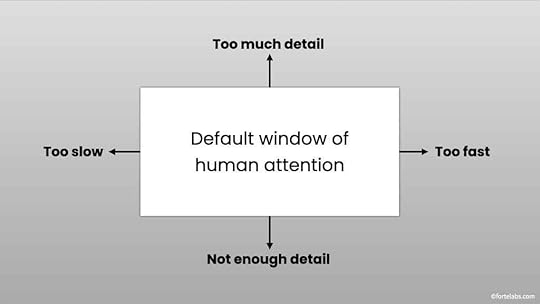

The crucial thing to understand is that we have a minimum AND maximum threshold for BOTH the time we’re willing to spend and the number of details we’re willing to process:

If it takes too much time, we get impatient and opt out (think of a movie where not enough is happening to hold your attention)If it doesn’t take enough time, we get overwhelmed and opt out (think of a short-form video that is so fast it’s aggravating to watch)If it presents too much detail, we get frustrated and opt out (think of a book going way too deep into a technical topic you don’t understand)If it presents not enough detail, we get bored and opt out (think of a children’s book with not enough complexity to be interesting to us)In other words, as humans, we have a clearly defined “window of attention” that limits what we’re able to pay attention to for long periods. Our attention span is an actual span with clear limits. Anything outside of that – that either moves too slowly or too quickly, that demands too much of our brains or too little – is tremendously expensive for us to attend to.

When you say “I don’t have patience for that,” you’re not saying you don’t have enough time. You’re really saying “That is below the level of detail I can sustainably process at the required rate.”

Thomas Carlyle once said, “Genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.” The word “pain” is informative in this sense – it is actually painful for us to stay outside our window of attention for long. The brain has a “focal length” it is comfortable with, like our eyes, and that attention span evolved for chasing and hunting down an animal about our own size, or picking fruit from trees; anything outside of that feels unnatural and painful for us.

This might seem like a discouraging and even fatalistic view of human potential: there are just some things we can pay attention to, and some we can’t.

But there’s another detail that Rao highlights here: that time and detail interact and influence each other. They are not independent variables: changing one actually changes the other.

Consider that looking at a raindrop with your naked eye might be boring, but if you zoom in with a microscope, you’ll see millions of microorganisms blooming and buzzing in stunning diversity. The classic example of “watching paint dry” would be terribly exciting if you could zoom in to the molecular level and watch the symphony of chemical reactions playing out.

In other words, the more you zoom in, the faster things are happening. The rate at which time passes for you depends partially on how much information you can take in. It’s not that time is actually speeding up or slowing down – your perception of time is speeding up or slowing down, and that perception is strongly influenced by how much detail and complexity you can take in and process.

Considering this idea, perhaps it is not people’s intelligence that limits what they can pay attention to and learn: it is their patience. And what limits their patience is not some stoic quality of their character, but their ability to zoom in and take in enough detail that reality feels interesting.

This also changes our view of what exceptionally patient people are doing. It’s not that they have some inner reserve of steely endurance – it’s that they’re better at operating at a level of detail where things happen faster.

The gardener absorbed in the intricacies of trimming a bonsai tree, or the basketball player shooting hundreds of free throws in one practice session, or the chess grandmaster playing through dozens of alternatives of a match – maybe these people aren’t abnormally patient; they’re just better at zooming in to a level of detail in their craft that the full bandwidth of their attention can be occupied.

We tend to think of patience as primarily a moral virtue, alongside work ethic, honesty, integrity, and empathy. What if instead we removed the moral framing, and thought of it instead as a side effect of the way we consume information?

AI could be used to tweak and tune information with the goal of fitting it into our preferred window of attention. Instead of treating the content we consume as one-size-fits-all, we could use AI to modify that content so that it’s at the right speed and the right level of detail such that it feels captivating and enlivening for us to pay attention to.

If a piece of content is too detailed, we can ask AI to summarize and distill it for us in ways that a novice can understand. If a piece of content is not detailed enough, we can ask AI to elaborate and add more sources and examples.

If a piece of content is coming at you too fast, you can ask AI to slow it down, break it into chunks, and give it to you one piece at a time. If it’s coming too slowly, you can ask it to move faster and progress to more advanced topics sooner.

I can foresee a future in which we rarely consume a given piece of content without changing it to suit our preferred window of attention. A future in which we run all our content through an AI curator who refines and modifies it to fit how our brains work. Not doing so will feel like buying a pair of shoes without trying them on for size.

In that future, patience won’t be considered a moral virtue – it will be considered a failure to properly utilize the tools at our disposal to customize our experience according to our needs.

If you’d like to read the Substack post by Venkatesh Rao called Oozy Intelligence in Slow Time yourself, click here.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Digital Attention Spans: AI as a Source of Infinite Patience appeared first on Forte Labs.