The problem with a root cause is that it explains too much

The recent performance of the stock market brings to mind the comment of a noted economist who was once asked whether the market is a good leading indicator of general economic activity. Wonderful, he replied sarcastically, it has predicted nine of the last four recessions. – Alfred L. Malabre Jr., 1968 March 4, The Wall Street Journal

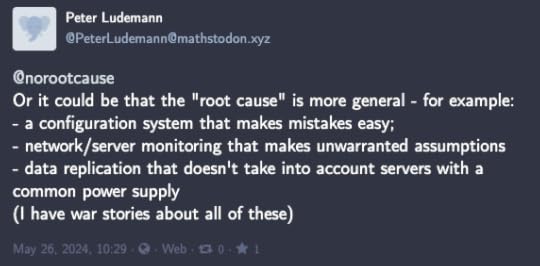

In response to my previous post, Peter Ludemann made the following observation on Mastodon:

This post makes the case for why I would still call these contributors rather than root causes, even though they certainly sound root-cause-y. (They’re also fantastic examples of risks that are very common in the types of systems we work in, but that’s not the topic of this particular post).

Let’s take the first one, “a configuration system that makes mistakes easy.” I’d ask the question, “does an incident occur every single time somebody uses the configuration system?” I don’t know the details of the particular incident(s) that Peter is alluding to, but I’m willing to bet that this isn’t true. Rather, I assume what he is saying is that the configuration system is fundamentally unsafe in some way (e.g., it’s too easy to unintentionally take a dangerous action), and every once in a while a dangerous mistake would happen and an incident would occur.

What this means is that the unsafe configuration system by itself isn’t sufficient for the incident to occur! The config system enables incidents to occur, but it doesn’t, by itself, create the incident. Rather, it’s a combination of the configuration system, and some other factors, that trigger incidents. Maybe incidents only manifests when there is a particular action a user is trying to take, or maybe some people know how to work around the sharp edges and others don’t, or other things.

This may sound like sophistry. After all, the configuration system is an unsafe operator interface. The lesson from an incident is that we should fix it! However, here’s the problem with that line of thinking. The truth is that there are many types of these sorts of problems in a system. I like to call these problems vulnerabilities, even though people usually reserve that term in a security context. Peter gives three examples, but our systems are really shot through with these sorts of vulnerabilities. There are all sorts of unsafe operator interfaces, assumptions that have become invalidated with change, dangerous potential interactions between components, and so on. These vulnerabilities are the sorts of issues that the safety researcher James Reason referred to as latent pathogens. Reason is the one who proposed the Swiss cheese model, with the latent pathogens being the holes in the cheese.

My problem with labeling these vulnerabilities as root causes is that this obscures how our systems actually spend most of their time up, even though these vulnerabilities are always present. Let’s say you were able to identify every vulnerability you had in a system. If you each one as a root cause of an outage, then your system should be down all of the time, because these vulnerabilities are all present in your system!

But your system isn’t down all of the time: in fact, it’s up more often than it’s down, even though these vulnerabilities are omnipresent. And the reason your system is up more than it’s down is that these vulnerabilities are not, by themselves, sufficient to take down a system. If you label these vulnerabilities as root causes, you make it impossible to understand to how your system actually succeeds. And if you don’t know how it succeeds, you can’t understand how it fails. You’re like the economist predicting recessions that don’t happen.

Now, whether we label these vulnerabilities as root causes or not, they clearly represent a risk to your system. But we have an additional problem: we live in the adaptive universe. That means we don’t actually have the resources (in particular, the time) to identify and patch all of these vulnerabilities. And, even if we could stop the world, find them all, and fix them all, and start the world again, our system keeps changing over time, and new vulnerabilities would set in. And that doesn’t even take into account how patching these vulnerabilities can create new ones. The adaptive universe also teaches us that our work will inevitably introduce new vulnerabilities because we only have a finite amount of time to actually do that work. Mistaking problems with individual components with the general problem of finite resources is the component substitution fallacy.

In short, labeling vulnerabilities as root causes is dangerous because it blinds us to the nature of how complex systems manage to stay up and running most of the time, even though vulnerabilities within the system are always with us. Now, these vulnerabilities are still risks! However, they may or may not manifest as incidents. In addition, we can’t predict which ones will bite us, and we don’t have the resources to root all of them out. We use “this just bit us so we should address it because otherwise it will bite us again” a heuristic, but it’s an implicit one. What we should be asking is “given that we have limited resources, is spending the time addressing this particular vulnerability worth the opportunity cost of delaying other work?”