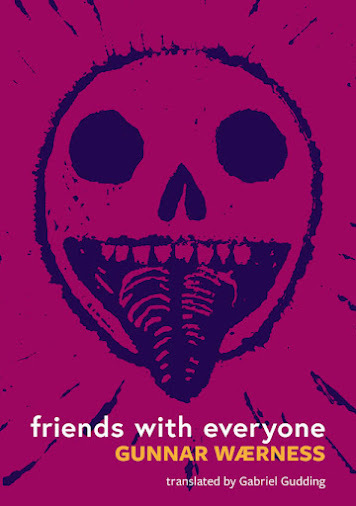

Gunnar Wærness, friends with everyone (trans. Gabriel Gudding

the shadow of thehomeland is a sea

that follows us in ourjourney it waits for us

beside the rivers that resemble blue intestines

spilling from thefolds of the map we stole

i conjure from thistangle of viscera and bowels

the carcass we called theworld we chased it with swords

first in boats then books and at last with this

one bare hand that burns here on your thigh goddess

which you brush away saying if you want to fuck

comrade you have to stop calling me momma

these are not mywords that are crawling down the edge

of the map of theworld drawn with crushed cochineal

soot and blood on vellum here where the seas and grown small

and the countries havedisappeared while the rivers havewidened (“6. (such a friend to everyone / march 23 2015”)

I’mintrigued by the punk swagger of musical, muscled language of Norwegian poet Gunnar Wærness' poetry collection

friends with everyone

(Action Books,2024), a collection that offers his poems in original Norwegian alongsideEnglish translation, as translated by American poet and translator Gabriel Gudding. The collection is constructed out of fifty-five numbered poems acrosssix sections, or “waves,” with final, seventh “wave” made up of a single,coda-like poem set at the end. Throughout, the poems accumulate across anarrative expansiveness, each building upon the prior, some of which are quitelengthy, almost unwieldly, across multiple pages. There is an element of thiscollection reminiscent of so many of those hefty Nightboat Books selecteds,offering whole new worlds and histories of writers of whom I had previously andcompletely unaware (it is always good to be regularly presented with new worldsbeyond one’s borders), and Wærness’ poetry, at least as evidenced through thiscollection, is polyvocal and explorative, providing an outreach one can neverquite see the horizons of, beyond the stark works set upon the page. “you areyour own / many-mentioned / heretic-angel,” the poem “21. (the angel of history/ june 1 2015)” begins, “all of us who believed in you / each plucked something/ from your fire as a souvenir // onyour yellowed image / the contones and rasters / are your fire’s cinders [.]”And there’s something of the date set in so many of the poem titles, jumpingaround in time and space, that provide a kind of untetheredness; it suggestsdates of composition, perhaps, but might also be a kind of red herring, or evenproviding dates from original composition, set in this particular order throughand for other means. One might wonder if the collection might provide adifferent shape if the poems were set in sequential order as suggested by eachdate instead of the poems’ numbering systems, or if the very notion of Wærness’expansiveness would render such reordering entirely moot. As Gudding writes toopen his post-script, “And the Carcass Says Look”:

I’mintrigued by the punk swagger of musical, muscled language of Norwegian poet Gunnar Wærness' poetry collection

friends with everyone

(Action Books,2024), a collection that offers his poems in original Norwegian alongsideEnglish translation, as translated by American poet and translator Gabriel Gudding. The collection is constructed out of fifty-five numbered poems acrosssix sections, or “waves,” with final, seventh “wave” made up of a single,coda-like poem set at the end. Throughout, the poems accumulate across anarrative expansiveness, each building upon the prior, some of which are quitelengthy, almost unwieldly, across multiple pages. There is an element of thiscollection reminiscent of so many of those hefty Nightboat Books selecteds,offering whole new worlds and histories of writers of whom I had previously andcompletely unaware (it is always good to be regularly presented with new worldsbeyond one’s borders), and Wærness’ poetry, at least as evidenced through thiscollection, is polyvocal and explorative, providing an outreach one can neverquite see the horizons of, beyond the stark works set upon the page. “you areyour own / many-mentioned / heretic-angel,” the poem “21. (the angel of history/ june 1 2015)” begins, “all of us who believed in you / each plucked something/ from your fire as a souvenir // onyour yellowed image / the contones and rasters / are your fire’s cinders [.]”And there’s something of the date set in so many of the poem titles, jumpingaround in time and space, that provide a kind of untetheredness; it suggestsdates of composition, perhaps, but might also be a kind of red herring, or evenproviding dates from original composition, set in this particular order throughand for other means. One might wonder if the collection might provide adifferent shape if the poems were set in sequential order as suggested by eachdate instead of the poems’ numbering systems, or if the very notion of Wærness’expansiveness would render such reordering entirely moot. As Gudding writes toopen his post-script, “And the Carcass Says Look”:In August 2022 abouttwenty Scandinavian poets and critics gathered for a symposium in Sundsvall,Sweden, to discuss the work of Gunnar Wærness (pron. Varniss)—in front of,with, and despite the misgivings of Wærness himself: I was fortunate enough toattend. The symposium principally focused on only one of Wærness’s severalbooks, Venn med alle. The Danish poet Glaz Serup asked Wærness about themany voices being sounded from the “I” in the book: from which or what realityor realm are these voices speaking? It’s an understandable question: everythingspeaks in Friends with Everyone. Or maybe: it’s more that speech isdistributed across a range of entities, a crowd of voices, sometimesdemocratic, sometimes geologic, sometimes botanical. Nonhuman animals speak asthey blink into extinction, the sea speaks, a mite speaks, rocks and treesspeak, the collective hiveghost of colonizing white people speaks, a prisoner,a cup, a goddess, a bowl, an eye, a tongue, a flower, a fetus. Lenin speaksfrom cupboards and drawers. We hear from unborn children and the dead speakfrom unknown realms. Even words speak in order to ask to be spoken. And somehowbehind these voices are other voices: the mite seems to ventriloquizeimmigrants, while poets are trying to ventriloquize whole nations. The wholebook seems suffused with monstrous speech, a gothic panpsychism. The issue thenin Friends with Everyone is reliably present: who or what speaks andwhy? To whom are they talking? And who is the friend?