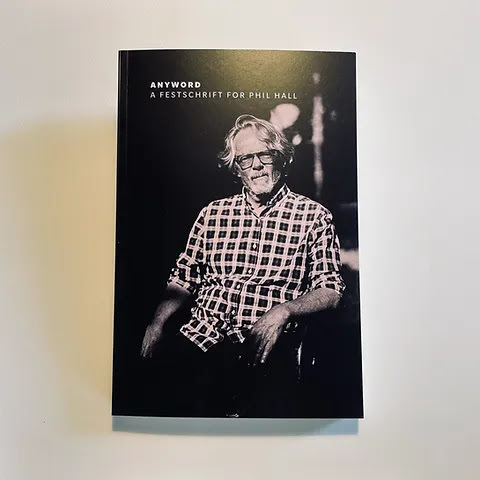

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik

It must be noted thatHall is one of the most widely and deeply read people I know. Years after hewon the Governor General’s Award, he told me that, “It’s very, very difficultto recognize a good work.” Moreover, Hall has a Master’s degree which hecompleted at the University of Windsor in the 1970s. No small feat, consideringHall was the first person in his family to finish high school. When I askedHall why he didn’t pursue a PhD (which he’d considered) he said, “Because I didn’twant it to dry me out.”

The idea for thisFestschrift was inspired in 2021 by the publishing efforts of the inimitablepolymath Nick Drumbolis and his remarkable imprint LETTERS. And though thisFestschrift is a gathering of writings for Hall as he turns 70, it is not abirthday party. It is an opportunity to give thanks for the years of steadyfriendship, mentorship, and work that he has provided. (Mark Goldstein, “Preface”)

I’mnot usually in the habit of reviewing a collection I have work in, but recentlya Canadian contemporary said they didn’t know what a “festschrift” was, sothought that prompt enough to discuss the recent

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL

, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik (Toronto ON: BeautifulOutlaw Press, 2024). Unlike the more formal essay series produced by, say, Guernica Editions (another essential grouping of responses), the literary festschriftallows for more of a range of responses-as-celebration, from the critical tothe creative and all between, from essays and interviews to small memoirpieces, poems and photographs.

I’mnot usually in the habit of reviewing a collection I have work in, but recentlya Canadian contemporary said they didn’t know what a “festschrift” was, sothought that prompt enough to discuss the recent

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL

, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik (Toronto ON: BeautifulOutlaw Press, 2024). Unlike the more formal essay series produced by, say, Guernica Editions (another essential grouping of responses), the literary festschriftallows for more of a range of responses-as-celebration, from the critical tothe creative and all between, from essays and interviews to small memoirpieces, poems and photographs.Festschriftsproduced by a trade publisher do occasionally (very occasionally) emerge, butover the past few decades in Canadian writing, at least, it had been thejournals doing the bulk of this kind of work, with a variety of special issuesthrough The Capilano Review focusing on works by Robin Blaser, GeorgeStanley [see my review of such here], Sharon Thesen [see my review of such here] and George Bowering, among others, or Open Letter: A Canadian Journalof Writing and Theory (1965-2013), a journal that included specialfestschrift issues on bpNichol, Steve McCaffery [see my review of such here],Barbara Godard [see my review of such here] and Ray Ellenwood, not to mention avariety of other journals over the years that have less frequently featuredspecial issues on particular writers, whether Arc Poetry Magazine onErín Moure, Prairie Fire on Dennis Cooley or The Chicago Reviewon Lisa Robertson [see my review of such here], etcetera. Given how far the festschriftseems to have fallen by the wayside (mainly through a slow decrease ofproper publisher funding and that 1990s drop-off in library funding, whichreduced their purchasing power), I began producing a series of similarchapbook-sized festschrift publications during the Covid-era throughabove/ground press (I thought the Covid period could use some increased positive)—the “Report from the Society” series—with more than a dozen published volumesto-date, which also includes one on the work of Phil Hall (a reworked versionof Susan Gillis’ piece from mine appears in this current collection).

Theremight be those who recall

A Trip Around McFadden

(Toronto ON: The FrontPress/Proper Tales Press, 2010), the festschrift produced by Stuart Ross and JimSmith to celebrate David W. McFadden’s 70th birthday, or thecombined four hundredth issue of 1cent/thirteenth issue of news notes thatjwcurry produced on the work of Judith Copithorne (“for Judith with love”) [see my review of such here], but how many might recall

Raging Like a Fire: A Celebration of Irving Layton

(Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1993), thefestschrift edited by Henry Beissel and Joy Bennett? There are probably others,naturally, that I’m either unaware of, or simply can’t recall at the moment,but either way, there simply aren’t as many out there as should be. Volumessuch as these are important parts of literary conversation and acknowledgement(as are volumes of selected poems, something that occurs far less since the GovernorGeneral’s Award declared them ineligible for consideration back in the late1990s), none of which is occurring nearly enough, so a volume on award-winning Perth, Ontario poet, critic, editor, mentor and teacher Phil Hall, especially one sobrilliantly and thoroughly done, becomes an essential commodity.

Theremight be those who recall

A Trip Around McFadden

(Toronto ON: The FrontPress/Proper Tales Press, 2010), the festschrift produced by Stuart Ross and JimSmith to celebrate David W. McFadden’s 70th birthday, or thecombined four hundredth issue of 1cent/thirteenth issue of news notes thatjwcurry produced on the work of Judith Copithorne (“for Judith with love”) [see my review of such here], but how many might recall

Raging Like a Fire: A Celebration of Irving Layton

(Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1993), thefestschrift edited by Henry Beissel and Joy Bennett? There are probably others,naturally, that I’m either unaware of, or simply can’t recall at the moment,but either way, there simply aren’t as many out there as should be. Volumessuch as these are important parts of literary conversation and acknowledgement(as are volumes of selected poems, something that occurs far less since the GovernorGeneral’s Award declared them ineligible for consideration back in the late1990s), none of which is occurring nearly enough, so a volume on award-winning Perth, Ontario poet, critic, editor, mentor and teacher Phil Hall, especially one sobrilliantly and thoroughly done, becomes an essential commodity. Inmany ways, one can’t get much better than the short essay “Landscapes,” by Br.Lawrence Morey, a contributor who lives as a Trappist monk at the monastery ofGethsemani in Kentucky, that opens: “I first became aware of Phil Hall’sexistence when I was in grade 9 and he was in grade 10. I had taken out thebook Cariboo Horses by Al Purdy from the school library, which I loved. Thosewere the days in which you would write your name in the back of the book on asmall, pasted-in form, along with the due date, which corresponded to a card inthe librarian’s files. In front of my name on the form, I saw the name PhilHall. I knew Phil to see him, but didn’t dare approach him, since I was a mere9th grader and he lived at the exalted level of the 10thgrade.” This particular perspective on Hall’s ongoing work is wonderful (andMorey’s biographical detail, itself, provides a curious insight into Hall’s Gethsemani sequence), as Morey writes, later on:

Though poetry is Phil’s main medium, he also loves tomake quirky sculptures out of found objects, bottle caps, paperclips, and otherthings. Like the work of Kurt Schwitters, his sculptures grow like livingcreatures. His journals are a mixture of writing, drawing, and pasted words andimages. I think this reflects his working methods beautifully. In everything hedoes, he takes disparate pieces of things, letters, words, phrases, sequences,and molds them into something new, something surprising and revelatory.

Overthe past decade, Toronto poet, editor, critic, publisher and book designer MarkGoldstein has evolved into one of Hall’s most thoroughly-considered supportersand critics, having now produced three full-length collections by Hall throughhis Beautiful Outlaw Press—Toward a Blacker Ardour (2021), The AshBell (2022) and Vallejo’s Marrow (2024)—as well as a chapbook (Essayon Legend, 2014) and postcard (Rampant, 2022) in small editions. Producedand co-edited by Goldstein, ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL may be wonderfullyexpansive and even exhaustive, but it should be noted that his own contributionsinclude the essay “A Maker’s Dozen: from Eighteen Poems to Killdeer,”a whopping sixty-six page essay that examines, as he writes at the offset, “PhilHall’s published body of work from 1973 to 2011. With a focus on form (as wellas syntax and subject), I will investigate Hall’s line through thirteen tradeeditions and how it changed over the nearly forty-year span since he first sawhis work published.” Living writers, especially those still active and engaged,are rarely provided such thorough, thoughtful examination, and Goldstein shouldbe commended for not only this piece, but his ongoing critical work, whichitself is provided not nearly as much attention as it deserves [see my reviewof his 2021 Part Thief, Part Carpenter: SELECTED POETRY, ESSAYS, AND INTERVIEWS ON APPROPRIATION AND TRANSLATION, produced through Beautiful Outlaw as well, here]. As Goldstein writes as part of his lengthy essay:

To be clear, by employing the term poetic form, I ampointing to the structural and organizational patterns of a poem, including its(subtle or more obvious) rhyme scheme, meter, stanza structure, lineation,sentence structure, and other elements that shape its overall configuration anddesign on the page. In light of free verse, poetic form has played asignificant role in the development of contemporary poetry, as poets like Hallhave experimented with new forms and pushed the boundaries of traditionalstructures to create highly readable yet neoteric and innovative styles of writing.

As I’ll show in this essay, Hall’s sense of form wasfirst influenced by both traditional and modern forms of poetry found withinthe canon, and later it was increasingly written in concert and conversationwith contemporary and postmodern poetry itself. Hall is a careful reader of alltypes of poetry (and literature) and has thought deeply about form. He has consideredhis own use of free verse and, rather than adhering to accepted rules or anti-rulesof meter and rhyme – whether outmoded or contemporary – he has, over time,experimented with myriad structures and patterns in his poetic line. This haslikely afforded Hall a greater flexibility in expressing his ideas and emotionsin poetry. This has also pushed him to develop new poetic forms of his owndesign, as well adapt or redeploy older ones – such as the prose poem and the haibun– to his own unique use. Moreover, Hall has slowly gravitated toward anexpansive use of his own idiosyncratic forms and sub-forms which are drawn fromthe dictates and necessities of his own poetry’s deployment.

Against a more prescribed approach to form, Hall hassaid, “What are we making? Sausage?”

Atmore than three hundred pages and twenty-six contributors, ANYWORD: AFESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL includes poems, essays, reminiscences andinterviews by George Bowering, Erín Moure, Don McKay, Sandra Ridley, GeorgeStanley, Steven Ross Smith, Tom Dilworth, Cameron Anstee, Br. Lawrence Morey,Mark Goldstein, Susan Gillis, myself, luke hathaway, Nicole Markotić, Fred Wah,Louis Cabri, Karl Jirgens, Arthur Craven, Chris Turnbull, Ali Blythe, JohnSteffler, Pearl Pirie, Donald Winkler, Ronna Bloom, Andrew Vaisius and AngelaCarr, as well as an array of photographs of Hall over the years—including anearly 1980s photo at Michael McNamara’s apartment on page 272 where he looksthe spitting image of a late 2000’s former Ottawa poet Jesse Patrick Ferguson—anda healthy bibliography of Hall’s published work. The responses run the gamut fromthe personal to the intimate to the critical and the celebratory (with most incorporatingmost if not all of those features), many of which I’m still working my slow waythrough reading [the video of the zoom-launch for the collection, which included readings by Hall, Moure, Blythe, Ridley and myself, is now online]. AsAngela Carr writes to introduce the first of two interviews she conducted withHall: “Phil Hall is to poetry in Canada what style is to reason.” The essay byPearl Pirie is easily the strongest critical work I’ve seen by her to date, andboth Moure and Blythe offer pieces that delight in their scale and intimatescope. The collected pieces offer such appreciation and delight, attempting toshare or discern the shapes of how Hall reacts, presents and writes, and boththe generosity and curiosity of a writer decades-deep into an appreciation ofhow the poem moves, or might move, or could move. It becomes hard to highlightmuch in this collection without wanting to reproduce whole pages, which I won’tdo here, but I shall leave the last words to Hall himself, out of one of thoseinterviews conducted by Angela Carr, where he speaks of the late Stan Draglandin such a way that it could be applied to Hall and his work, as well:

It is a style (one thingreminds me of another) that can easily go wrong. If a writer seems to bepadding, if a writer seems to be flailing or name-dropping, if the examplesseem too carefully or metaphorically fetched. But Stan makes in his essays eachstep of his argument seem inevitable, so that we say, “Of course!” Then, at theend of an essay by him there’s that feeling of having participated in a dance –& having gotten somewhere unexpected, wider.

It has a lot to do withtexture. And character. And with a widening of community. During the time I knewStan, from 1984 until this year, he moved toward an on-rush of critical herding& gathering that can be breathtaking to read. Breathtaking in its humility& faith. He had a deep faith in us. He believed that we, his friends, wereworth it – worth every quirky added bit – and worth every word.