The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Works Both Ways

Note: This is an op-ed with no cited research!

We recently saw a spectacular production of Purpose, an epic family drama by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, at Steppenwolf theater in Chicago. The parents in this family both project their expectations onto their two sons and label them unfairly, leading both sons to live up to those labels.

The play was a provocative exploration of family relationships that led to an hour-long discussion on the way home. To my surprise, that dialogue brought me to my frustration with the high school where I taught in Connecticut. That school offered five sections of freshman English, and they were labeled Honors, High Average, Average, Low Average, and X. Impotent as a brand-new teacher there, already planning a move to Illinois, I was powerless to convince the administration that such labels are harmful. Being called “average” may not encourage students to reach for greater success, but its impact pales in comparison to the damage done by a label like “low average,” not to mention “X.” I taught five sections that included two “average,” two “low average,” and one “X.” It must not come as a surprise that my classes lived up to [down to?] their labels, that my low average class made limited effort, and that my X class behaved terribly and did little work. I like to think that I made some progress in dispelling those labels, and I did eke some achievement out of all my students. But this experience offered the most blatant example of how important the way we label and describe people can be.

When I landed at Glenbard West, we had three levels of English for the first three years: Honors, Regular, and Basic. While those labels seem less hurtful, getting my “Basic” students to see themselves as achievers remained an uphill battle. I loved the smaller class size and less rigid curriculum that I could tailor to each class, but too many of my students accepted the premise that they were remedial students and could not expect to be successful.

I struggled to change their minds. I addressed these students formally, Ms. Smith and Mr. Jones, to show my respect. I seized on their best moments for genuine praise, like when one of my girls prompted a great discussion about why Curley’s wife doesn’t have a name like all the male characters. Together they were able to guess that Steinbeck wanted readers to see her merely as Curley’s property. When another student, responding to events in another book, said aloud, “When you choose not to choose, you have chosen,” I turned it into a poster for the class to see daily. And when one of those classes complained about being bored, I responded [as I always did] that “boredom is in the eye of the beholder.” They remained unconvinced, so I urged them to write about it. They produced this collaborative poem:

Boredom,

you walk around with nothing to do

you are the dull grey of an old movie

without the crispness of black

or the freshness of white

you stalk schoolrooms,

invading English and Biology classes –

even social studies and driver’s ed

are not immune to your attack.

You are invisible and sneak up on us,

Shutting down our brains

while our yawns gape, making teachers angry.

By English II-B

February, 1991

I was so pleased with their sensory details, impassioned emotions, and thoughtful word choice that I convinced them to submit their poem to the jury process for Page to Stage, our annual performance of student writing. When it was chosen, they insisted they would not read it aloud on stage, that I should ask theater and speech students to read it for them. Knowing a bit about reverse psychology, I assured them I would do that if they weren’t up to the task. After some rehearsal during class time, they chose to participate, and watching them stand taller and taller during their choral recitation to an enthused audience is one of my favorite teaching memories. In my early years at West, I saw some of my “Basic” students go on to college, including one who went to a four-year school, something none of them would have predicted.

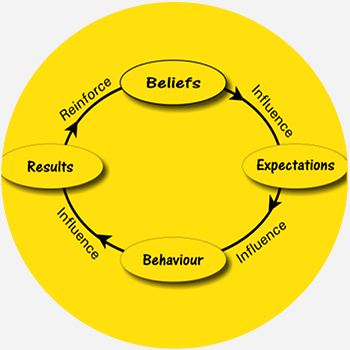

During the years of folded computer printer paper, when you’d just tear between pages as needed, I printed a multi-page version of a favorite quote that decorated my classroom wall: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, else what’s a heaven for?” My belief that my students could achieve seemed to help them do just that. But when we label learners, we give them the wrong message. When we call students “Basic” or – heaven forbid! – “X,” we tell them we don’t think they can succeed. Too often they will live up to those negative expectations. We know better. We should do better by our students. We should avoid labels where we can and choose encouraging labels when we must use them. All of us fall prey to self-fulfilling prophecies, and we must stop setting students up for low expectations and failure. They deserve better.