Books that Did It For Me

Everyone has books that changed them. They’re books that made ah-ha moments, books that shifted their writing, offered them something, or gave them something to think about. I have several.

In no particular order, here they are.

The Prince of Tides, Pat ConroyI was eleven when I found The Prince of Tides in the back of my parents’ GMC Jimmy. We were driving back from the mountains, and I was bored, so I flipped it open and started reading. I found these words:

My wound is geography. It is also my anchorage, my port of call.

To understand their effect, you have to realize that I didn’t grow up in a house with William Shakespeare; I had never read Thomas Wolfe or F. Scott Fitzgerald. My childhood was full of plain books, and no poets dwelt under my parents’ roof—or maybe, reading those words, that’s when one was born. I honestly didn’t know that anyone could write like that:

When I was ten I killed a bald eagle for pleasure, for the singularity of the act, despite the divine, exhilarating beauty of its solitary flight over schools of whiting. It was the only thing I ever killed that I had never seen before. After my father beat me for breaking the law and killing the last eagle in Colleton County, he made me build a fire, dress the bird, and eat its flesh as tears rolled down my cheeks . . . He believed in the expiation of sin.

Let me reiterate that I was eleven years old. Mind. Blown.

My mother found the book and took it. Irony: she let me read everything Stephen King ever published, including It, but took The Prince of Tides because of the graphic rape scene (apparently, Apt Pupil was okay?!). I never forgot it, because it remained the only time my parents ever censored my reading. Conroy’s words lingered; I wrote snippets of his prose in a notebook—from memory; I scratched them in Catholic school cursive after she confiscated the book.

Years later, I found The Prince of Tides again and finished it. I stole Beach Music, too. I was applying to college at the time, and the kids in the novel go to the University of South Carolina. If it’s good enough for Pat Conroy, I thought, it’s good enough for me. My parents were after me to apply to a state school—I’d confined myself to Ivies and privates—and when USC’s Honors College dean personally called and offered me a giant scholarship, I accepted.

World War Z, Max BrooksI read this novel when it first came out, and it sticks with me for several reasons. It’s a perfection of a post-apocalyptic tale; Brooks hits on national character in a way that few other authors have ever managed. Because of South Africa’s history of apartheid, they have the Redecker Plan ready to go; because of their history of apartheid, Israel implements it perfectly (to their credit, they don’t discriminate between Palestinians and Jews, either, only humans and zombies). Americans have the Zombie Reality TV, but we’re also the first to fight them back—along with a guy who someone’s “pretty damn sure was Michael Stipe.”

This found-footage novel really shows the possibilities of voice. I was enraptured at the idea of using a multiplicity of characters to tell a story; Brooks is masterful at it. This novel deserves a lot more attention, from a craft standpoint, than it’s currently receiving.

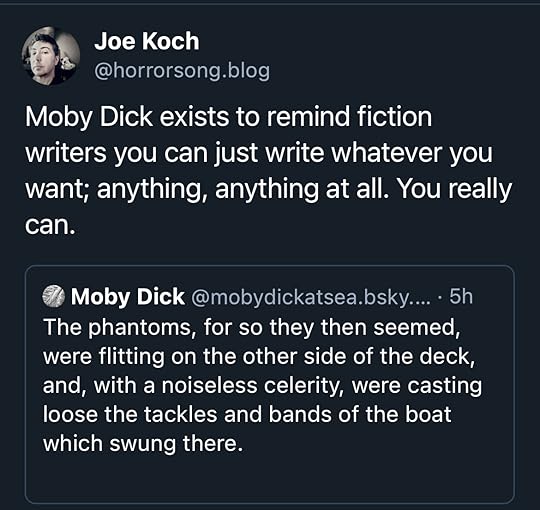

Moby Dick, Herman MelvilleThis is the greatest horror novel ever written. This is, in fact, the greatest novel ever written. It’s beautiful, startling, terrifying, hilarious, and shocking in turns. Even boring, and that on purpose.

My friend Jonathan and I believe, I’d argue rightly, that pretty much everything can be related to Moby Dick. It’s a tome that can be used a sort of Bible, a touchstone, maybe a divination text. There’s an inherent mysticism to it. What is it but a battle between man and the unknowable, uncaring other, and what could be more horrifying? I don’t think it’s an accident that Chris Carter compares Mulder’s search for the truth to Ahab’s pursuit of the whale.

We can learn a lot, lyrically, from Melville.

Basically All of FaulknerAbsalom, Absalom! is my favorite, but I love it all. The Sound and the Fury is widely regarded as Faulkner’s best, probably rightly, since the voices are so stunning throughout (as are the voices in A Light in August), but my heart will always belong to that Gothic spiral of a novel. I love the image of Rosa Coldfield creeping to Sutpin’s Hundred with an ax in her hand, and also this, which I literally cannot read without crying, because it’s so fucking good:

Then in the long unamaze Quentin seemed to watch them overrun suddenly the hundred square miles of tranquil and astonished earth and drag house and formal gardens violently out of the soundless Nothing and clap them down like cards upon a table beneath the up-palm immobile and pontific, creating the Sutpen's Hundred, the Be Sutpen's Hundred like the oldentime Be Light. Then hearing would reconcile and he would seem to listen to two separate Quentins now-the Quentin Compson preparing for Harvard in the South, the deep South dead since 1865 and peopled with garrulous outraged baffled ghosts, listening, having to listen, to one of the ghosts which had refused to lie still even longer than most had, telling him about old ghost-times; and the Quentin Compson who was still too young to deserve yet to be a ghost but nevertheless having to be one for all that, since he was born and bred in the deep South the same as she was-the two separate Quentins now talking to one another in the long silence of notpeople in notlanguage, like this:

The plot of Absalom, Absalom! can be summed up in one, perhaps two sentences. It’s a miracle of structure; the plot is revealed as the novel spirals tighter and tighter, until it comes to a shattering, horrific conclusion. The prose is stunning. The setting is unforgettable. I listened to it as I drove to South Carolina recently, finished it, cried at the last line, then started it again. It’s everything a Gothic novel should be.

The Collected Stories of Flannery O’ConnorShe’s not mean, not really. Flannery O’Connor loves people, but she sees their inherent fallenness. She’s an astute observer of the inherent absurdity of man. Her stories are worth reading for their lovely shimmer of lunacy; O’Connor sees the raw red heart of the South and serves it up on a platter. Bible salesmen who steal legs, Temples of the Holy Ghost, raging bulls, monkeys at barbecue barns—O’Connor loves them all.

No shock that she’s from Savannah, the most Southern of all Southern cities, where the South reaches its illogical apotheosis of madness.

All of F. Scott FitzgeraldI have a story about Fitzgerald.

Much like Conroy’s The Prince of Tides, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby blew my tender little psyche: In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. The green lights, the beautiful little fool, the shirts . . . ! I knew I’d found a masterpiece. I was fifteen, and I fell in love.

A year later, I was admiring a painting in my friend Ceci’s house. “Zelda did that,” she said.

I planted my hands on my hips. “I only know one Zelda,” I said, “and you don’t have her paintings in your house.”

She gave me a strange look. “Uh, Zelda Fitzgerald is my great-grandmother,” she told me.

Ceci and I liked to mess with each other—we’d once convinced a friend that the term for Danish people was “Denmarkian”—so I threw her a look of sheer disdain. “No, she’s not.”

“Yes, she is,” Ceci said.

“No, she’s not,” I replied.

Ceci dragged me into the kitchen. “Mom, tell her who your grandmother is,” she demanded.

Her mother gave me an are-you-serious look. “Zelda Fitzergald,” Cecilia told me—the daughter of Scottie Fitzgerald, Cecilia Lanahan, whose son, my crush, was named Scott. One of my best friends, whom I’d known for years, was the great-granddaughter of freaking F. Scott Fitzgerald. Apparently everyone had known this but me, because I was (and am) chronically oblivious.

I went on to adore all Fitzgerald’s short stories and novels, leading to a very embarrassing moment, after college began, when the Rosses asked who my favorite writer was. I was forced to admit it was Fitzgerald.

It was only one of the many embarrassing moments surrounding Fitzgerald during college; when I picked USC, I didn’t know that it was home to the most illustrious Fitzgerald scholar in America, Matthew J. Bruccoli. I also didn’t know that he was involved in a lawsuit with the Lanahan family over the publication over early drafts of The Great Gatsby, titled Trimalchio in West Egg. Bruccoli was very interested to discover that I had grown up with Ceci and grilled me about the Rosses (I told him nothing); the Rosses were interested to know I took classes with Bruccoli (I told them everything). He was, in the main, a wonderfully disgruntled man, prone to shouting at Judy, his secretary, to get Sotheby’s on the phone. Ask how he was doing and he’d bark, “Still vertical!” When he passed, a tragedy for American letters, I ended up being among the people who cleaned out his office furniture. We discovered a racy romance stashed at the top of a bookshelf, and I kept it.

Later, I ate what I thought were grapes at the dilapidated hotel in Tryon, North Carolina where Fitzgerald wrote Tender is the Night. They were poisonous, and I threw them up before they killed me. I generally read all of Fitzgerald’s stories at least once a year. His descriptions of character are the standard to which I hold my own.

I could keep rambling, but those are the highlights. Of course, I read too much Stephen King too young. I was obsessed with David Eddings (later, I’d be devastated to realize how colonial and racist his novels are), Christopher Pike, and R. L. Stine. Latin American magical realism, especially Marquez and Cortazar, are huge influences of mine. When it comes to poets, I love Simic and Stevens.

And of course, I love House of Leaves, Twin Peaks, and all things Mike Flanagan.