Elizabeth Clark Wessel, None of It Belongs to Me

Pioneer Women

My great-greatgrandmother Theresa

homesteaded her own acres

after her husband died ofa headache.

She sent her childrenaway until

they were old enough todrive a plow.

She was a Christian womanand canny—

the other pioneer womensent for her

when their times werenear.

Pioneer women had manybabies,

and many babies died.They had hearts

to break. Once I stood ona hill

surrounded by the gravesof pioneer women

and their children,throwing handfuls

of my grandmother’s ashinto a wind

that is always present;on every side

and below me ran straightlines of crops

in need of more waterthan the sky can give.

The crops are wrong forthe land,

which prefers the ancientgrasses.

In the lean years—or sothe story goes—

pioneer women ground upgrasshoppers

to make their bread.

They had meanness todrive them on.

They could give up almostanything

so they did. They wereoffered land

if they could keep it,and when they got it,

they put up fences. Theymust have known

their presence was afence. While all around them

the dirty work of killingto keep the land went on.

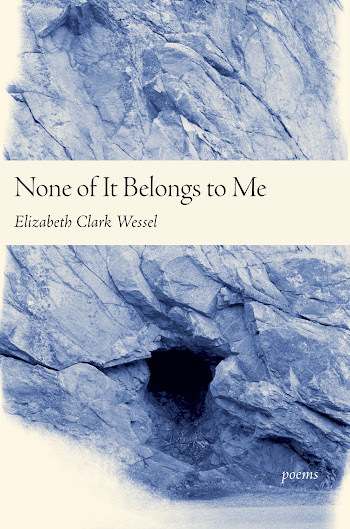

Itwas through a chapbook produced in 2018 by Daniel Handler’s Per Diem Press [see my review of such here] that I first had the opportunity to explore the work ofAmerican-in-Sweden writer, editor, translator and publisher Elizabeth Clark Wessel, so I am very pleased for this further opportunity, through the publicationof her full-length debut,

None of It Belongs to Me

(Boston MA: Game OverBooks, 2024). She even has a birthday roundabout now, if the ending of her poem“Mary Wollstonecraft” is to be taken at face value (which could be consideredspeculative on my part, admittedly): “Today is my birthday / It’s cold and notyet spring / The minutes tick by relentlessly / We can never know where / we’reon our way to / and I will never be content / with this box of words / But I wouldlike to leave it now / teetering at the edge / without tipping over [.]”

Itwas through a chapbook produced in 2018 by Daniel Handler’s Per Diem Press [see my review of such here] that I first had the opportunity to explore the work ofAmerican-in-Sweden writer, editor, translator and publisher Elizabeth Clark Wessel, so I am very pleased for this further opportunity, through the publicationof her full-length debut,

None of It Belongs to Me

(Boston MA: Game OverBooks, 2024). She even has a birthday roundabout now, if the ending of her poem“Mary Wollstonecraft” is to be taken at face value (which could be consideredspeculative on my part, admittedly): “Today is my birthday / It’s cold and notyet spring / The minutes tick by relentlessly / We can never know where / we’reon our way to / and I will never be content / with this box of words / But I wouldlike to leave it now / teetering at the edge / without tipping over [.]”Iappreciate the clarity of her lines, a lyric that plays with the accumulationof straight phrases and its variations, such as the poem “The Ersatz Viking Ship,”that begins: “I wake up. / I drink coffee. / I take the words of one language./ I put them into another language. / My goal is to keep the meaning. / What I thinkthe meaning is.” There is a practicality to the narrative voice she presents, apragmatism to these lyric threads: aware of what terrible things might occurbut refusing to be overcome by them, simply allowing for what can’t be changed,and sidestepping what can easily be avoided. “my advice to you is / always thesame,” she writes, as part of “My Advice,” “check the lock by picking it /leave the scabs on as long as you can stand / avoid whatever you feel / likeavoiding for as / long as that’s a workable strategy [.]” There is an optimismthat comes through as sheer perseverance and persistence, able to continuethrough, because of and no matter what. “After giving birth it starts to hurt.”she writes, to open the poem “Love Poem at Thirty-Seven,” “And then there’s nodrive left. / Like a spent animal who has outrun / her predator. No energy to /seek it out. The flesh, the breath, / the deflated balloon of skin, the marks.”Wessel offers directions through her accumulation that appear, at first,straightforward enough, instead providing a sequence of turns, sweeps, bendsand even twists across the lumps and bumps of her narratives. I would love tohear these poems read aloud, honestly. And the straightforwardness of her linesoffer a mutability that can play with expectation, always providing a safe handto hold through even the darkest places. As the poem “Sticks” ends: “It crashedonto us, crushing what wouldn’t be penetrated. / What I mean to say is theworld kept ending, and we kept on / loving each other anyway. Isn’t that dumb. Isn’tthat just / the dumbest thing you ever heard.”