We Need to Talk About Your Rivers

The “rule of cool” is a common piece of advice for artists. Let your imagination run wild. And that applies to fantasy as well. By its very nature, rules are meant to be broken. It’s part of the mystique. It’s why the genre can be so compelling. But to really break the rules effectively, it helps to have a solid comprehension of the underlying contexts. The rule of cool can backfire when we push boundaries without some rudimentary knowledge of the foundations on which boundaries are based. Instead of feeling vibrant and innovative, the work can come across as lacking depth and intention, losing its logical consistency, and coming across as hackneyed, as if we’re not putting in the effort required to create something meaningful.

Mouth of the Platte River, 900 Miles above St. Louis, by George Catlin, 1832

Mouth of the Platte River, 900 Miles above St. Louis, by George Catlin, 1832That brings me to today’s topic: rivers.

When it comes to rivers, I’ve noticed that quite a few fantasy writers don’t understand the basics. While their intent is noble, I’ve seen plenty of examples of authors struggling with the underlying science of rivers and river systems. I sympathize. These are mistakes I have made myself. Early on, in one of my first projects, I made a mess with the waterways in my fantasy world. Mistakes like these—I like to jokingly call them “river sins”—might go unnoticed at first, but when they are noticed, they can draw a reader out of the story or setting. It wasn’t until I later learned more about the behavior of these ecosystems that I was able to hone in on my worldbuilding, and the end result was something much more interesting and complex. The cool got cooler.

Rivers and waterways have played an influential part in humanity’s history, so it makes sense they also have a meaningful place within our fantasy work. Civilizations have been built around their tendrils of life. Battles have been fought over their control. They have served as highways, borders, walls, temples, power plants, and the source of fresh water and food. It’s no wonder they play a part in our stories. I’ve worked with fantasy maps for a while now, and my experience has given me a unique insight. Information I wish I had early on when I started my first forays into worldbuilding. I’ve found by following a few simple tips, you can use river systems more effectively within your fantasy stories and use them to enhance your work and further draw a reader into your creation.

What are those tips? Let’s talk about them.

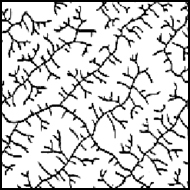

Rivers are FractalOne of the biggest mistakes I see comes from a misunderstanding of how rivers behave. Water seeks a path of least resistance; they are fractal for all intents and purposes. Smaller streams feed into more significant streams. They flow from a higher elevation toward a lower one. These are called Stream Orders, with the smallest being tiny 1st-Order headwater streams and the largest being enormous 12th-Order rivers. Depending on the geology, watersheds can flow in various patterns—the tree-like dendritic systems, the angular rectangular systems, the narrow parallel systems, the unpredictable contorted/deranged systems, and more. Still, the end result is the same, smaller waterways flowing into more prominent channels and then into even bigger ones before they empty into a basin of some sort. (We’ll get to those later.)

Dendritic

Parallel

Trellis

Rectangular

Radial

Annular

Multi-Basinal

Contorted

Examples of drainage basins by A. P. Howard, AAPG, 1967

Rivers are AliveUnless your fantasy world has a corp of engineers, odds are your river will be alive and unpredictable. It’ll move and change channels; sediment will build up, causing a shift down a different path. An earthquake will happen, causing a landslide, and suddenly, a new lake is formed, and the water will find a new exit. A log jam upstream might send a river in a completely different direction, leaving a former river town high and dry. Depending on a river’s stage, these can happen quickly, or these shifts can take years. But unless it’s forced by humans (or beavers), your rivers will move. This movement is called a meander, and it can create some fascinating landscapes. Dry rincons, cutoff oxbow lakes, and point and scroll bars are all formations built by a river’s meander. While these meanders don’t necessarily have to play a part in your plot, knowing that rivers move is essential when laying them down in your fantasy world.

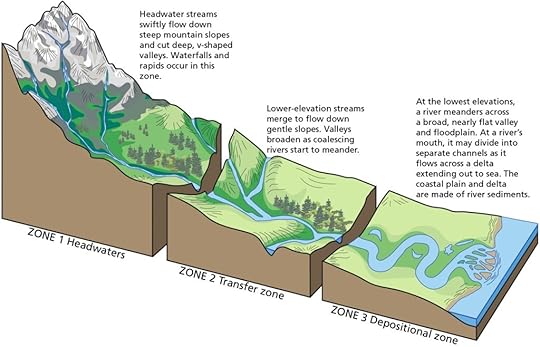

Rivers Have Three StagesThese are classified as youthful, mature, and old. This isn’t a reflection of a river’s actual age, but its behavior, and a single river might have multiple stages along its course.

YouthfulThese waterways have a steep gradient, few tributaries, and a fast flow. Its channels erode deeper rather than wider. (Zone 1 in the illustration below.) The Skoga River in Iceland is a youthful river.Mature

These rivers have a gradient that is less steep than those of youthful rivers and, as a result, flow more slowly. Many tributaries feed a mature river, and they have more discharge than a youthful river. Its channels erode wider rather than deeper. (Zone 2.) The Ohio River in the US is a mature river.Old

Like a curvy river? Then you’ll appreciate the old rivers. A river with a low gradient and low erosive energy. Meanders, oxbow lakes, and broad floodplains characterize old rivers. (Zone 3.) The Indus River flowing from the Himalayas would be considered an old river.

Source: Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, Colorado State University.If Your River Crosses a Continent, It’s Not a River

Source: Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, Colorado State University.If Your River Crosses a Continent, It’s Not a RiverThis is a mistake I see way too often. Rivers that start at one ocean cross a continent or landmass and end in another. Rivers don’t do this. (Sorry, East River, you’re a fraud.) They can’t. This is not a river. This would be a strait. If your oceans are salty, then that straight would be salty. Rivers can flow into your strait. But the strait must be at sea level to behave this way. You won’t find a river flowing from one side of a continent to the other without human interference—these are most commonly called canals—and even then, you’ll be connecting different systems, often flowing in separate directions. Remember: water always flows downhill. We divide our oceans, but the reality is they’re all connected—they’re technically one vast basin. Oceans don’t drain into themselves. The sea level is the base.

Rivers Only Permanently Split at Deltas*Bifurcation is the term used to describe when a river splits. It’s how river islands are born. Most of the time, the secondary distributary channel will reconnect with the primary channel, forming those islands. Sometimes, those separations are large; more often, they’re small. It’s very unusual for a river to split otherwise. That said, this changes when in a river’s delta.

A delta is a flat expanse of land where the river meets the sea. Deltas come in all shapes and sizes. They can be enormous mega deltas or relatively minor. It’s not uncommon for them to incorporate an estuary. Estuaries often turn into deltas as sediment builds. Bifurcation in these areas can be extreme as the land is now at or near sea level, and the river moves and braids based on the distribution of sediment and the power of its discharge. While not always the case, you’ll often find a primary channel through a delta with many bifurcated smaller channels breaking away before finally terminating into the drainage basin.

Examples of various river deltas. (Nichols, 2009)Okay, Let’s Talk About That Pesky Asterisk

Examples of various river deltas. (Nichols, 2009)Okay, Let’s Talk About That Pesky AsteriskThere are some sporadic but notable examples of natural bifurcation, leading to unusual drainage systems. These tend to be on smaller waterways and are extremely rare (I can’t stress that enough), but occasionally, you’ll find some instances on larger river systems or through bifurcation lakes. We’ll talk more about the former since it’s the fantasy river sin I see the most, but it’s also worth looking into the latter.

The 200-mile Casiquiare Canal is one of the few large natural canals connecting two separate river drainage systems. But this sort of bifurcation isn’t permanent; with time, sediment, and no human interference, it’s likely the Casiquiare will be entirely diverted into the Amazon basin. Without interference, other instances of this sort of distributary system will also face similar shifts over time.

Often, if a distributary is long enough, it will be labeled as a new river. But you won’t find instances where Yangtze-sized rivers naturally split into two rivers permanently without an outside influence. Eventually, stream capture would occur, and one channel would die away to become a wind gap while the other would become the river’s main channel.

It’s worth looking into these systems if you’re looking for a unique landscape for your characters to explore, more so if you want to give them a navigational challenge, but understanding the complications and being able to write to them will only enhance your work.

On Inland Deltas & Inland Seas & EstuariesInland Deltas form when a river flows into an enormous valley or basin with no point for discharge, and often, they are surrounded by desert—the Okavango Delta in Botswana is the largest on the planet. Usually, the delta forms a vast wetland, and as the water moves further into the valley, it eventually evaporates around the edges. These deltas are broad, marshy, interconnected, and relatively shallow. The discharge of the river feeding these deltas would determine their size.

Inland Seas are a little different and are really divided into two categories. If they’re connected to the ocean, they are essentially enormous brackish bays. Something changes if they sit within an Endorheic basin and have no drainage. The water here forms enormous saltwater lakes with a higher salinity than freshwater. They get their excess minerals from evaporation. Size and location affect their salinity. The Caspian Sea has a salinity of about a third of the oceans. The Great Salt Lake, on the other hand, is smaller and can be as much as seven times saltier than the ocean.

Estuaries are partially closed bodies of brackish water. They can be a part of deltas or found on their own. For the most part, they are affected by tides or waves and also experience the sediment and freshwater of fluvial influences. There’s a wide variety of estuaries, and their unique mix of sea and freshwater creates fascinating examples of transitional zones.

There are some neat ecological systems around inland seas, deltas, and estuaries, and they’d make interesting settings, but knowing how they work is key to creating a vibrant ecosystem for your characters to explore or endure.

Mules pulling boat up canal, 1904 – Via

Library of Congress

You Can’t Sail Up Rivers

Mules pulling boat up canal, 1904 – Via

Library of Congress

You Can’t Sail Up RiversI wrote a whole article about this when I saw it happen on Amazon’s Lord of the Rings show The Rings of Power. It’s worth checking out if you want more than a bullet-point explanation. The reality is it is very difficult and complicated to sail upriver. The bigger the boat or ship, the harder it will be. It wasn’t until the development of machinery that humans found a rapid way to move heavy vessels (and holds full of heavier cargo) upriver. Before then, you needed to row, pole, or pull your craft upriver, and the bigger it was, the harder the work. Currents and winds are not our friends here, and they wouldn’t be in any pre-industrial fantasy either. That said, we always have the magic of… er, magic.

In ConclusionThat covers some of the basic tips surrounding waterways and drainage systems. I tried to keep the information relevant and not delve too far into the weeds—each of these tips could be expanded into books of information. Hopefully, as you set about creating your fantasy world for your book or game, you’ve found this guide helpful, and you can avoid those early mistakes I made.

As I’ve worked with fantasy maps over the years, I’ve seen all sorts of river sins. Some of those sins have embarrassingly made their way to print. You’d be surprised how many popular novels screw up. (And after reading this, I bet you’ll notice them yourself. Sorry!) The good news is that working in fantasy allows us to break all of these rules. We can follow the rule of cool! You don’t even have to waste a lot of time explaining your choices. A magic-powered boat can sail upriver! A god-like monster can split a river in two or pull seawater inland! River serpents can plow through marshland to create natural canals! The largest body of water in your world could be a vast inland sea! There are endless ways to construct the setting you want, but to do it well requires intention, and knowing how rivers naturally work can help make your intentions more unique and fantastic. It only enhances the rule of cool. That is the key to building a more lush, vibrant, and fantastical world, a world where readers can get lost for a while. And if we’re not doing that, what are we doing?

Castle by a River, Oil on Wood,

Jan van Goyen

, 1647, Via

The Met

Castle by a River, Oil on Wood,

Jan van Goyen

, 1647, Via

The Met

Want to stay in touch with me? Sign up for Dead Drop, my rare and elusive newsletter. Subscribers get news, previews, and notices on my books before anyone else delivered directly to their inbox. I work hard to ensure it’s not spammy and contains interesting and relevant information. Sign Up Today →