Not just words

This past autumn, archaeologists working in Turkey in the ruins of the ancient Hittite capital Hattussa around 100 miles east of modern Turkey’s capital, Ankara, discovered a previously unknown ancient Middle Eastern language that had been lost for up to 3,000 years.

The Hittites were one of the dominant powers of the Near East between the 15th and 13th centuries BC, even conquering Egypt for a time. Their empire stretched from the Aegean Sea in the west to northern Iraq in the east, and from the Black Sea in the north to Lebanon in the south. Their civilization changed human history with technological innovations like the use of iron, their famous war chariots and the creation of a substantial civil service.

Massive empires are run by information, and this ancient domain was no different – the civil service scribes kept voluminous records, all in a Hittite version of a pre-existing Mesopotamian script called cuneiform, which consisted of wedge-shaped lines arranged in groups representing syllables.

During excavations over recent decades, around 30,000 clay tablet documents have been unearthed. Most were written in the empire’s main language, Hittite, but around 5 percent were in the languages of the empire’s minority ethnic groups from various parts of Anatolia, Mesopotamia and Syria.

The area where modern Turkey now lies was, in ancient times, rich in languages. Currently only five minority languages have been known from the time of the Hittites, but there would once have been many more, making this recent discovery very exciting. The newly-discovered language is being called Kalasmaic, apparently spoken by a conquered group of people in an area called Kalasma on the empire’s northwestern fringe. Its discovery opens up a bigger window into one of the largest administrative regions in history.

What is language? We speak it every day, having learned it as a child, and having expanded our vocabulary over time. You’re reading this in English, obviously, which I’ve studied over the years to find fluidity and eloquence as a writer. I was also a member of Toastmasters for several years to learn how to express myself better orally (and not freeze up in meetings at work, which were the bane of my existence for years beforehand).

In high school I studied French (Canada’s second language) and Latin (because I thought it was interesting). But before I began elementary school I was fluent in German, which we spoke at home. I’m rusty on the German and French now because I don’t have many opportunities to use them, but in my travels I’ve used them both, as well as picking up some Spanish.

According to the internet, there are over 7,000 languages in the world – far more than most of us would think or be able to name. But according to The Bible, depending on how much you might believe as a historical document:

Genesis 11:1-9 (NIV)

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech.

This sentence in The Bible begins the story of the Tower of Babel, and it’s a very curious tale.

As a species, we arose in Africa. Language – using sounds, then groups of sounds, then words and sentences – is believed to have developed as early humans needed to convey information, about food, danger, etc. No one will ever know for sure of the exact timeline, but over the millions of years in which we evolved physically, it wasn’t until we became homo sapiens that we had the right vocal equipment to produce speech. It’s believed that we began ‘speaking’ to each other about 20,000 years ago.

It’s extraordinary that humanity existed for 7 million years without being able to talk amongst themselves. What a quiet place the planet must have been, just the sounds of nature and the few sounds early humans could have made (grunts, yells?). Sounds rather pleasant, doesn’t it?

Around 2 million years ago, early humans began dispersing beyond Africa. The first cave painting, the earliest form of communication that our species has, dates back to over 64,000 years ago (using uranium-thorium dating) and was made by a Neanderthal.

Once humans began moving to different places in the world, and then developed speech, it’s a bit of a stretch to believe that the entire world had only a single language, as stated in Genesis. Yet there’s that chronicle, which goes on to say:

As people moved eastward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there.

They said to each other, “Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.” They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

But the Lord came down to see the city and the tower the people were building. The Lord said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

So the Lord scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. That is why it was called Babel—because there the Lord confused the language of the whole world. From there the Lord scattered them over the face of the whole earth.

The words of the story leave a lot out. Why were the people so determined to build the tower, for example? (Scholars have speculated that this was a post-Flood attempt to catastrophe-proof themselves.) What’s meant by the tower ‘reaching the heavens’? (The sky? God’s domain?) Why was God so worried about anything us piddly humans could do anyway? It’s unclear, but God actually reached down and made the people no longer able to understand each other, which was as good a way of messing things up as any.

The effect of confusing our language was profound. The people gave up their construction entirely, even though surely they still remembered how to build, and left the region to go and live somewhere else.

Scholars believe this was a tale not to be taken literally, but to explain the existence of multiple languages and cultures in the world.

Being able to understand and speak another language opens up travel in amazing ways. My hubby and I always try to learn a few words in the language of the country we’re visiting, as a courtesy to the people who live there. We picked up a little Arabic for our trip to Egypt, a little Indonesian for visiting Java and Bali, brushed off our high school French for a jaunt to Paris…

When we were in Peru, where Spanish, Quechua (the language of the Inca people), and Aymara are the official languages, and English is spoken to some degree, I was able to communicate fairly well in my travel Spanish. Spanish is one of the “Romance” languages, derived from Latin (the high school stuff has come in handy), and with the aid of that base reference and a vocabulary book, I made out pretty well. But when we visited two islands in Lake Titicaca, including an overnight ‘home stay’, it was a challenge to manage more than a couple of words in Aymara, which is unlike any other language we’ve come across. It’s certainly not related to Latin, and possibly not Quechua either. Thankfully for travellers, people on the islands and in neighbouring Bolivia also speak Spanish, and if I wanted to purchase a handicraft or ask a question, I was able to get by, and I felt very empowered to be able to manage even that small level of communication.

As a lot of us growing up in the 20th century had drilled into us, Words are Important. So is writing them down in a form that others can read.

The Bible isn’t the earliest piece of compiled and written oral traditions in history – writing goes back to ancient Sumer, dating to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC (or BCE). Writing, even in its most basic forms, opened up a whole new world of preserving information. But not all writing is necessarily in a form we’d recognize

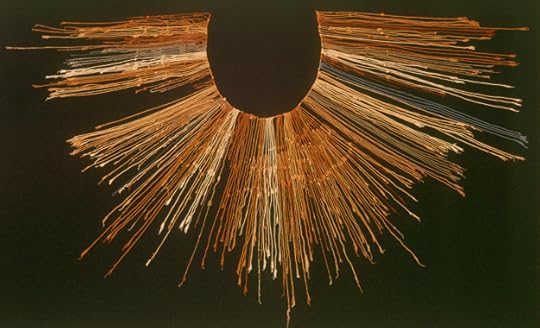

For example, for a long time historians have believed that the Inca, builders of the largest empire in South America, had no form of writing; all the information about one of the greatest cultures in history has come from the Spanish invaders, and from surmises made from artwork and other cultural artifacts. The Inca had a complex counting system using coloured strings with knots in them, knows as “quipu”, but there are very few surviving quipu to study.

An Inca quipu, from the Larco Museum in Lima

An Inca quipu, from the Larco Museum in LimaBy Claus Ableiter nur hochgeladen aus enWiki – enWiki, hochgeladen von User Lyndsaruell; siehe http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Inca_Quipu.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2986739

What’s been known about quipu, or khipu, is that the Inca people used them for keeping calendrical and numerical records of various things like taxes, census records, military organization. The knots recorded data using a base-ten numerical system, with the absence of a knot in specific positions to represent ‘zero’.

Seems straightforward enough, but a single quipu could have only a few cords, or up to thousands of them. And in recent years, some researchers have begun to speculate whether those cords also contained a form of writing/language that we aren’t familiar with. Recently, American anthropologist Sabine Hyland believes she’s begun to make headway in understanding the language, identifying 95 combinations of colour, ply and type of fibre; that would be enough to comprise a writing system.

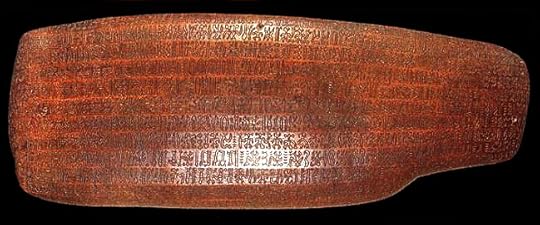

There are still a variety of writing systems we’ve never deciphered, because they’re so different we don’t even know where to start. Rongorongo, the writing found on Easter Island, is one of them.

Verso of rongorongo Tablet B, Aruku Kurenga.

Verso of rongorongo Tablet B, Aruku Kurenga.By Rongorongo_B-v_Aruku-Kurenga_(color).jpg: unknown *derivative work: Mfield (talk) – Rongorongo_B-v_Aruku-Kurenga_(color).jpg, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34608081

Archeologists aren’t even certain that the markings, on some two dozen surviving artifacts, are writing/language, but their precise positions in long strings on layers of lines look like they’d be strings of information. However, if you look at the sample above, there’s no punctuation or spacing to help delineate words and sentences, at least none that we recognize.

Linear A, used by the ancient Minoan civilization in palaces and for religious writings, is another famous undeciphered language, although it is recognized as script,. It was succeeded by Linear B, which has been deciphered, but Linear A remains a mystery.

We take languages for granted, but there are still so many that we can’t read, that are rare and disappearing, and that have even gone extinct when the last known speaker passed away.

For centuries people had no idea what all those beautifully-scribed hieroglyphs in Egypt were saying, as the knowledge of carving them disappeared around the 3rd century A.D. It wasn’t until Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 discovered the Rosetta Stone. This piece of black basalt, by a great stroke of luck, contained the same message in hieroglyphs, Demotic (another script that was used for documents as a kind of early ‘short-hand’), as well as – and this was the key to everything – in ancient Greek.

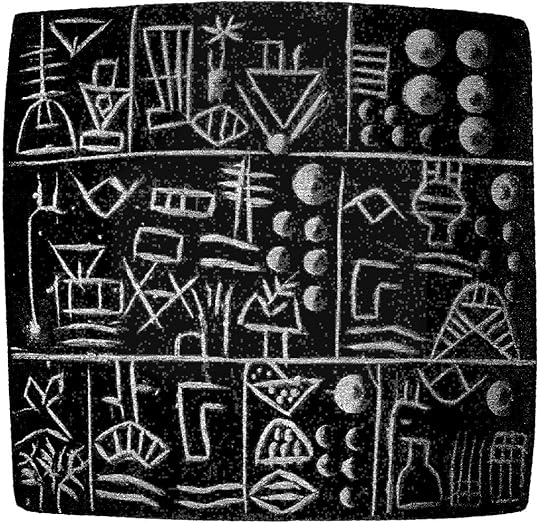

Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system, developed in ancient Sumer, which, as you might guess, is the earliest known civilization (a complex society that developed a governing body, social stratification, community living in a city/multiple cities, and a writing system). Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia (what’s now south-central Iraq) in the early Bronze Age. In the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers were able to grow an abundance of grain and other crops, which enabled them to stop being nomadic and form urban settlements.

Because the messenger’s mouth was heavy and he couldn’t repeat [the message], the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

Those words are from a Sumerian epic poem, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. c. 1800 BC, explaining the story of writing. Scribes used specially-cut reeds to produce a stylus that created the distinctive wedge-shaped characters that were then pressed into pieces of soft clay.

The cuneiform script was developed from an early form of what’s called “proto-writing” that was pictographic. The problem with recording in stylized pictures is that it’s cumbersome and time-consuming, and it was inevitable that, as the Sumerian civilization grew, they’d develop something that could be stamped in the clay a little faster.

Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC.

Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC.By Barton, George A. (12 November 1859 – 28 June 1942) – Origin and Development of Babylonian WritingPublished 1913, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77733268

Tomb of Darius I DNa inscription part II

Tomb of Darius I DNa inscription part IIBy Diego Delso – This file has been extracted from another file, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75161226

Over the course of its history, cuneiform was adapted to write a number of languages in addition to Sumerian.

A vast amount of cuneiform tablets have been recovered from archeological digs – between 500,000 and two million cuneiform tablets are estimated, of which only approximately 30,000–100,000 have been read or published so far. The British Museum holds the largest collection (approx. 130,000 tablets). Decipherment of cuneiform began in the late 1700s and translation of historical records continues to this day.

The unearthing of tablets with a newly-recognized language emphasize how much of the past is still waiting to be discovered, in ideas and even statistics, passed on across the centuries through words and phrases recorded where some day they could once again be read.

The post Not just words first appeared on Erica Jurus, author.