How to write compelling action: advice from an award winning author

Epic fantasy battle made with MidJourney

Epic fantasy battle made with MidJourneyI recently finished “The Faithful and the Fallen” by John Gwynne — a four-book epic fantasy series that is regarded by many to be one of the best ever written.

Gwynne is a Viking history buff. He and his sons partake in Viking reenactments and his two major series are very inspired by Norse history and mythology. One of the reasons his two series are held in such high regard is his accuracy in depicting battle scenes and great action.

The final battle in “The Faithful and the Fallen” was engrossing, and I’m a reader who often gets bored with drawn-out battles and action sequences. So why did this one hold my attention?

I had to stop and think about it. One thing for certain was that it was filled with personal grudges, redeeming acts, selfish motives, and more. Mostly, the battle was secondary to what the characters were growing through (sort of… they were also trying to save the world)

This led me to think of other series with action sequences that held my attention. The one that really popped to mind was “The Sword of Kaigen,” which if you’ve read my other posts, you know I adore.

How did the author, M.L. Wang, write fight scenes and battles that were so engaging and avoid the trap of throwing too much noise at the reader?

Well, rather than guessing and fretting over it, I just asked her.

M.L. Wang’s AdviceI emailed M.L. Wang and told her how much I loved “The Sword of Kaigen” (authors appreciate hearing how much fans like their work!) and I asked her how she went about balancing character-driven narratives with intense action.

I also asked her permission to use her response in this blog post — don’t quote people without their consent!

I’m going to break down what she said.

“Thank you so much for picking up The Sword of Kaigen, and I’m glad to hear you enjoyed it!

Re: your question about balancing action and character development scenes, I think the trap is conceptualizing these as two separate types of writing… I think that action is a language as much as English. Consequently, my favorite fight scenes read like conversations between characters and my favorite action sequences function as character development moments.”

I’ll admit that this shifted how I conceptualized these types of writing. As someone drafting a fantasy story with some action, I fell into the trap of telling myself “Action scenes are not good character development scenes.”

But M.L. Wang is absolutely right, especially when you are crafting a story where someone is skilled/competent in a particular way. And this isn’t just true in epic fantasy novels (as I’ll break down in a minute) — the same can be said for any type of competition.

M.L. Wang wrote a guest blog post on Where Words Bloom prior to the release of “The Sword of Kaigen” where she discussed some of this in more detail.

“The strategy I landed on, after months of trial and error, was to treat the action scenes of The Sword of Kaigen not just as ‘character scenes’ but as conversation. While your average street brawl might not carry more meaning than ‘I don’t like your face,’ a fight between skilled martial artists is an exchange with as much nuance and energy as the snappiest dialogue. This wasn’t something I understood until I was actually proficient at martial arts myself (not to say that you have to be a martial artist to grasp it; I’m just a slow and tactile learner). For years, sparring was an anxiety-inducing, no-fun nightmare for me, but it abruptly became engaging — and ironically, one of my favorite things — the day I realized that I had gotten good enough to converse with an opponent. Fighting, I learned, is like language; it’s more fun when you’re fluent.”

Thinking of action scenes as conversations is enlightening and the more I thought of other examples, the more I realized how accurate it is. We often recognize great dialogue as a hallmark of good writing, and when you broaden your definition of “dialogue” to include intent expressed through action, you’ll see why some authors can nail action scenes better than others.

“Most editors will tell you that if a line of dialogue doesn’t justify its place on the page — if it doesn’t provide new information, reveal or reinforce a personality trait, shift the balance of power between characters, force a decision or introspection, diffuse or escalate tension, or just make the reader feel something — it gets cut. By holding every strike, step, and stumble to that standard, I hoped to create fight scenes full of character.”

Fonda Lee, the author of the Green Bone Saga, also discussed this in her article “Martial Arts & Fantasy — More Please, But Better.” When you have characters are extremely competent in a particular skill, that skill becomes their way of communicating.

“In martial arts stories, the action scenes are character scenes”

Side note: I also received great writing advice from Fonda Lee about writing time skips.

Other types of competition

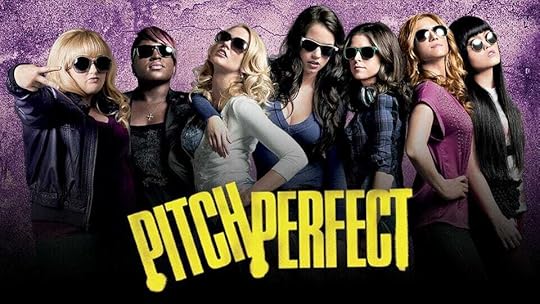

This advice can be applied to much more than just “fight scenes” or “big battles.” Take, for example, the movie “Pitch Perfect”. In the last sequence, where The Bellas are performing their closing act to clinch a victory at the Finals (sorry for the spoilers… but this movie came out 12 years ago and it is literally perfect, so if you haven’t watched it, that’s on you).

I won’t go into too much context here, but our main character Beca, played by Anna Kendrick (who, coincidentally, grew up a few miles up the road from me) has not only swallowed her pride to help her friends, but she is attempting to repair the damaged relationship with her love interest, Jesse (played by Skylar Astin).

She includes “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” in their closing mashup, one of Jesse’s favorite movies — a moment that earns her a fist pump. As an introverted and stubborn character, she took the opportunity to express her apology and appreciation through the action scene.

That last sequence is as much a conversation as a scene of straight dialogue.

Sports stories

Sports stories are especially great at this type of “action as a conversation” sequence.

The final episode in the first season of Ted Lasso is a great example. Jamie Tartt, who served as a pseudo-antagonist through the first season clinches a victory for his team over Ted Lasso’s Greyhounds not by being dominant, but by finally heeding Ted’s advice and passing the ball to share the glory. It’s a great moment not because it’s devastating for the protagonist, but because it’s a huge character moment without any words.

I can point to a dozen examples in sports films, but the best ones are always stories where the competition frames the character development.

ConclusionAs M.L. Wang says, treat action as a conversation. Whether it’s:

1. fight scene (The Sword of Kaigen)

2. musical performance (Pitch Perfect)

3. soccer game (Ted Lasso)

4. chess match (The Queen’s Gambit)

5. defending a barricade (Les Miserables)

This is doubly true for action scenes related to experts. A chess match between Grand Champions is as much a clash of personalities and ideologies as it is a game.

[image error]