THE HORN SNAKE AND THE HOOP SNAKE - FIERCE CRITTERS OF THE SERPENTINE KIND

Hoop snake in hot pursuit! (© Richard Svensson)

Hoop snake in hot pursuit! (© Richard Svensson)

Following on from my previous ShukerNatureblog article chronicling what may well be North America's most familiar folkloricFierce Critter of any kind, the truly monstrous hodag (click hereto access my article), I am now documenting the most (in)famous Fierce Crittersof the serpentine kind – namely, the horn snake and the hoop snake.

I must not forget, in these random sketches, myold friend and neighbour, Uncle Davy Lane...Nothing could move him out of aslow, horse-mill gait but snakes, of which "creeturs he was monstrous'fraid." The reader shall soon have abundant evidence of the truth of thisadmission in his numerous and rapid flights from "sarpunts."...Hebecame quite a proverb in the line of big story-telling. True, he had manyobstinate competitors, but he distanced them all farther than he did thenumerous snakes that "run arter him."...

"But at last I ventured to go into the faceuv the Round Peak one day a-huntin.' I were skinnin' my eyes fur old bucks,with my head up, not thinkin' about sarpunts, when, by Zucks! I cum right plumupon one uv the cuiousest snakes I uver seen in all my borned days.

"Fur a spell I were spellbound in three footuv it. There it lay on the side uv a steep presserpis, head big as a sasser,right toards me, eyes red as forked lightnin,' lickin' out his forked tongue,and I could no more move than the Ball Rock on Fisher's Peak. But when I seenthe stinger in his tail, six inches long and sharp as a needle, stickin' outlike a cock's spur, I thought I'd a drapped in my tracks. I'd ruther a harduvry coachwhip [snake] on Round Hill arter me en full chase than to a bin inthat drefful siteation.

"TharI stood, petterfied with relarm — couldn't budge a peg - couldn't even take oldBucksmasher off uv my shoulder to shoot the infarnul thing. Nyther uv us movednor bolted 'ur eyes fur fifteen minits.

"Atlast, as good luck would have it, a rabbit run close by, and the snake turnedits eyes to look what it were, and that broke the charm, and I jumped fortyfoot down the mounting, and dashed behind a big white oak five foot indiamatur. The snake he cotched the eend uv his tail in his mouth, he did, andcome rollin' down the mounting arter me just like a hoop, and jist as I landedbehind the tree he struck t'other side with his stinger, and stuv it up, cleanto his tail, smack in the tree. He were fast.

"Ofall the hissin' and blowin' that uver you hearn sense you seen daylight, ittuck the lead. Ef there'd a bin forty-nine forges all a-blowin' at once, itcouldn't a beat it. He rared and charged, lapped round the tree, spread hismouf and grinned at me orful, puked and spit quarts an' quarts of green pisenat me, an' made the ar stink with his nasty breath.

"Iseen thar were no time to lose; I cotched up old Bucksmasher from whar I'ddashed him down, and tried to shoot the tarnil thing; but he kep' sich a movin'about and sich a splutteration that I couldn't git a bead at his head, for Iknow'd it warn't wuth while to shoot him any whar else. So I kep' my distuncetell he wore hisself out, then I put a ball right between his eyes, and he ginup the ghost.

"Soonas he were dead I happened to look up inter the tree, and what do you think?Why, sir, it were dead as a herrin'; all the leaves was wilted like a fire hadgone through its branches.

"Ileft the old feller with his stinger in the tree, thinkin' it were the bestplace fur him, and moseyed home, 'tarmined not to go out again soon..."

H.E. TaliaFerro ('Skitt') – 'Uncle DavyLane'

Over the years, the annals of zoology havereceived and dutifully logged various reports of some truly remarkablepseudo-serpents, i.e. false snakes once deemed to be genuine species butsubsequently exposed as imaginative folktales, deceiving hoaxes, or monstrousmisidentifications. One of the most intriguing examples is the North Americanhorn snake – not least because it is actually two pseudo-serpents in one!Moreover, as noted above, both of them are derived from the rich FierceCritters folklore of this New World continent's early lumberjacks and otherrural pioneers.

The earliest notable account of the hornsnake appeared in American explorer John Lawson's important work A New Voyage to Carolina (1709; retitledThe History of Carolina in later editions), whose description succinctlyincludes all of the principal characteristics of this singular, highlycontroversial reptile:

Of the Horn Snake, I never saw but two that Iremember. They are like the Rattlesnake in Colour, but rather lighter. Theyhiss exactly like a Goose when anything approaches them. They strike at theirEnemy with their Tail, and kill whatsoever they wound with it, which is armedat the End with a Horny Substance like a Cock's Spur. This is their Weapon. Ihave heard it credibly reported by those who said they were Eye-Witnesses, thata small Locust Tree, about the Thickness of a Man's Arm, being struck by one ofthese Snakes at Ten o'clock in the Morning, then verdant and flourishing, atFour in the Afternoon was dead, and the Leaves dead and withered. Doubtless, beit how it will, they are very venomous. I think the Indians do not pretend tocure their wound.

Front cover of John Lawson's 1709 book A New Voyage to Carolina (public domain)

Front cover of John Lawson's 1709 book A New Voyage to Carolina (public domain)

In the 1722 self-revised edition of his1705 tome History and Present State of Virginia, Virginia historian andgovernment official Colonel Robert Beverley emphasised the nature of the hornsnake's stinging tail as a formidable weapon:

There is likewise a Horn Snake, so called from aSharp Horn it carries in its Tail, with which it assaults anything that offendsit, with that Force that, as it is said, it will strike its Tail into the ButtEnd of a Musket, from whence it is not able to disengage itself.

The first naturalist to document the hornsnake in detail was Mark Catesby, in the first volume of his major work TheNatural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1731), summarisingthe descriptions provided previously by Lawson and Beverley, but discountingits tail's deadly nature as outrageous fiction and identifying its species as a'water viper', to which he gave the formal name Vipera aquatica.According to Catesby, the horn snake's tail-sting or spine was merely a blunt,horny, and completely innocuous structure about half an inch long.

Water moccasin, threat display (public domain)

Water moccasin, threat display (public domain)

Curiously, however, the species that hedubbed Vipera aquatica and labelled as the horn snake is traditionallybelieved to have been the water moccasin Agkistrodon piscivorus - theworld's only species of semi-aquatic viper. Yet although it does possess ashort, thick, blunt-ended tail, the latter does not bear a spine at its tip.Consequently, some modern-day herpetologists dispute that Catesby's so-called'water viper' (and thence his horn snake) was indeed the water moccasin.

Notwithstanding Catesby's scepticismregarding the venomous nature of the horn snake's tail spine, this feature wassteadfastly reiterated in subsequent accounts elsewhere (so too was the claimthat this species was reddish or at least partly reddish in colour). And tocomplicate matters still further, a second, even more fantastic, zoologically-implausiblecharacteristic was soon attributed to this already much-muddled mystery snake –the supposed ability to turn itself into a vertical hoop by grasping its tailin its jaws just like the mythical ouroboros, thereby enabling it to roll alongthe ground at great speed like a living tyre. When carrying out this bizarremode of locomotion, the horn snake thus became known as the hoop snake.

Ouroboros drawing from a late medieval Byzantine Greekalchemical manuscript (public domain)

Ouroboros drawing from a late medieval Byzantine Greekalchemical manuscript (public domain)

An early hoop snake account was penned byAmerican traveller J.F.D. Smyth in 1784, following a stay in western NorthCarolina, and was published in Volume 1 of his multi-tome travelogue Tour inthe United States of America. After describing the by now familiarmorphological characteristics of the horn snake, Smyth added the following veryremarkable behavioural information:

As other serpents crawl upon their bellies, so canthis; but he has another method of moving peculiar to his own species, which healways adopts when he is in eager pursuit of his prey; he throws himself into acircle, running rapidly around, advancing like a hoop, with his tail arisingand pointed forward in the circle, by which he is always in the ready positionof striking.

It is observed that they only make use of thismethod in attacking; for when they fly from their enemy they go upon theirbellies, like other serpents.

From the above circumstance, peculiar tothemselves, they have also derived the appellation of hoop snakes.

The next couple of centuries saw manypublished reports of hoop-rolling horn snakes – hailing from a widegeographical spread, including the Minnesota-Wisconsin border, North Carolina,and British Columbia in Canada - despite their self-evident improbability. Atypical example, which concisely contains all of the intrinsic horn/hoop snakemotifs, is the following account, published on 8 November 1884 by an Australiannewspaper entitled the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiserbut documenting an alleged incident that took place in Virginia, USA:

One day last week a littlegirl, whose name slipped the correspondent's usually retentive memory, waschased by a monster hoop snake nearly a mile. Just as it seemed that it wasabout to strike her, she dodged behind a large apple tree. The rapidly whirlingsnake turned to follow and struck the tree with such force as to drive thehorn-spike into the hard wood over two inches. The child was so frightened thatshe sank down, her heart thumping as though it would burst out of her body.

One of her brothers, who hadseen her flying down the hill, went to see what was the matter. When he reachedthe tree it was quaking like an aspen and its leaves and fruit falling to theground in a perfect shower, the prostrate girl being almost buried beneaththem. As soon as he got her restored to consciousness he took a fence rail andkilled the venomous reptile, which was eleven feet two and a half inches inlength and eight inches in circumference. The horn point on the tail was sixand a half inches long, and so deeply imbedded in the hard wood that it couldnot extricate itself. This all happened near South Mountain, Va [Virginia].

With the girl's name convenientlyforgotten, the correspondent responsible for the account not named, and theeminently unlikely nature of the entire incident, the most reasonableassumption is that this incident, like so many others of its kind involvingextraordinary, unbelievable beasts, was a journalistic invention. Yet even today, supposedly serious reportsof hoop-rolling horn snakes are still being documented, thus sittinguncomfortably alongside unequivocally tongue-in-cheek, light-hearted versions,cartoons, and other jokey representations of this classic pseudo-serpent.

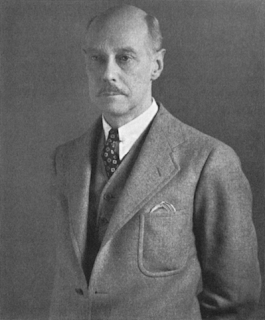

Raymond Ditmars (public domain)

Raymond Ditmars (public domain)

Moreover, it is nothing if not telling thatalthough celebrated American snake expert Raymond Ditmars (1876-1942) placed10,000 dollars in trust at a New York bank to be awarded to the first personwho provided him with conclusive evidence for the reality of the hoop snake,this very substantial prize was never claimed.

But are reports of horn and hoop snakesabsolutely fictional, or could there be at least a kernel of truth at the heartof such ostensibly unfeasible tales? Quite apart from the fact that there aremany fully-attested sightings of snakes grasping their tails in their mouths(albeit while lying on the ground, and therefore yielding horizontal circlesrather than the hoop snake's vertical ones), there are certain fully-recognisedspecies of North American snake that do bear a spiny structure at the tip oftheir tail. So it may be that some of these latter species have helped inspireand shape the legend of the horn snake.

Mud snake (© John Sullivan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Mud snake (© John Sullivan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

One of the leading candidates for this roleis the mud snake Farancia abacura, a semi-aquatic, non-venomous speciesof colubrid native to the southeastern USA. Up to 6 ft long, black dorsally,black and orange ventrally (with the orange sections extending upwardslaterally, thereby corresponding with certain horn snake accounts referring toreddish-orange sides), this distinctive snake has only a short tail, but itbears a noticeable spine at its tip, which in reality is a greatly-enlargedterminal scale of hard, horny constituency and quite sharp at its tip. Ofcourse, the spine is not venomous, but this species shares a sufficient numberof other characteristics with the legendary horn snake – both the tail spineand the shortness of the tail itself, a tendency to prod prey with its tailspine, plus orange flanks, and a water-frequenting preference – for there to belittle doubt that it has actively influenced traditional, non-scientific beliefin sting-tailed horn snakes.

Certainly, eminent American herpetologistDr Karl P. Schmidt (1890-1957) favoured this identity for the latterpseudo-serpent when documenting the horn/hoop snake saga in an articlepublished in the January/February 1925 issue of the American periodical NaturalHistory. This theory has also been championed much more recently, byanother American herpetologist, Dr J.D. Wilson, in a mud snake articlepublished by the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory in 2006, and not only forthe horn snake specifically but also for its locomotory hoop snake alter ego. Aclosely-related species, the rainbow snake F. erytrogramma, which againis semi-aquatic, non-venomous, native to the southeastern USA, and very similarto the mud snake by virtue of its body colouration, short tail, andreadily-visible tail spine, is actually referred to colloquially as the hoopsnake across much of its geographical range.

Coachwhip snake (public domain)

Coachwhip snake (public domain)

Yet another North American non-venomouscolubrid that has been implicated with the hoop snake legend is the coachwhipsnake Masticophis flagellum, endemic to the southern USA and alsonorthern Mexico. Up to 6.5 ft long, this species is sometimes reddish-pink incolour, recalling once again descriptions of the horn snake.

Moreover, although it does not possess atail spine, it is a fast-moving, very agile species, and Schmidt, among others,has suggested that the hoop snake component of the horn snake myth may haveoriginated from sightings of species like this one (as well as fellownon-venomous North American colubrid the common black snake Coluberconstrictor – and in particular its most distinctive subspecies, the blueracer C. c . foxii) gliding along at great speed and in an undulatingmanner over the tops of bushes without descending to the ground, thus recallingthe hoop snake's supposed rolling mode of progression.

Common black snake (public domain)

Common black snake (public domain)

Interestingly, horn and hoop snaketraditions are not exclusive to North America. Comparable tales have beenrecorded from Australia too. This island continent is home to the highlyvenomous death adders – a genus (Acanthophis) of viper-impersonatingelapids whose several species are all famed for their very conspicuous tailspine.

Central and West Africa are also sources ofsting-tailed horn/hoop snake reports, which in this case appear to have beeninspired by harmless blind burrowing snakes of the genus Typhlops, whichpossess very prominent tail spines. Moreover, Schmidt suggested that slavesbrought to North America from these regions of Africa may have contributed to theNew World horn snake folklore by recalling stories of African burrowing snakesthat subsequently became transferred to America's own equivalent species(though not of the genus Typhlops, as this is confined to Central andSouth America in the New World).

An Australian death adder (public domain)

An Australian death adder (public domain)

Yet regardless of the varied scientificexplanations documented and discussed that discount the horn and hoop snake asbeing wholly fictitious, belief in the reality and lethal nature of thesepseudo-serpents is still deeply ingrained among great swathes of the generalpublic across North America and elsewhere. So much so, in fact, that it seemslikely that their origins will forever remain controversial, and with any investigationsof scientifically-untrained eyewitness reports destined merely to go round andround in circles – just like the hoop snake itself!

Having said that, however, no article onhoop snakes could possibly close without mentioning a truly remarkablesomersaulting snake from the Philippines. Courtesy of a fascinating videoproduced by a longstanding cryptozoological friend, Tony Gerard, there is conclusiveproof of at least one species of snake's extraordinary ability to make dramaticsomersaulting leaps through the air when fleeing a perceived threat.

Northern triangle-spotted snake (© R. Brown et al., 2013/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0

licence

)

Northern triangle-spotted snake (© R. Brown et al., 2013/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0

licence

)The species in question is the northerntriangle-spotted snake Cyclocoruslineatus, a small, non-venomous member of the very diverse, elapid-relatedtaxonomic family Lamprophiidae and endemic to the Philippines. The video(posted here on YouTube by Americanherpetologist/cryptozoologist Chad Arment as StrangeArk on 19 May 2019) showsTony with one of these snakes held briefly under a bowl. When Tony lifts up thebowl and gently prods the snake, it rapidly flees via a series of very dramaticsomersaulting leaps through the air and across the ground, so that it bearsmore than a passing resemblance to the fabled hoop snake.

Indeed, the only reason why I am includingit here, rather than in an article dealing with jumping snakes, is that whereasthe hoop snake was said to turn itself into a hoop by gripping its tail in itsmouth and then rolling along like a vertical hoop or wheel, this Philippinessnake engenders its superficially hoop-like appearance by way of repeatedsomersaulting leaps, without ever grasping its tail in its mouth.

Vintage sketch of a hoop snake by Margaret R. Tryon (public domain)

Vintage sketch of a hoop snake by Margaret R. Tryon (public domain)

Nevertheless, the overall visual effect issimilar enough to make me wonder if other snakes can also accomplish suchsomersaults and, in turn, whether the hoop snake tales originated fromsightings of snakes performing this acrobatic ability, with the tail-in-mouthdetail being subsequently added in elaborated retellings. From such are myths,legends, and folktales born.

ThisShukerNature article is excerpted and adapted from my book SecretSnakes and Serpent Surprises, published by CoachwhipPublications.

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers