THE HIDEOUS HODAG - HISTORY OF A HOAX

Fibre-glasshodag statue in front of the Rhinelander Area Chamber of Commerce (© GouramiWatcher/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Fibre-glasshodag statue in front of the Rhinelander Area Chamber of Commerce (© GouramiWatcher/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Back in the pioneering days of NorthAmerica, when European settlers were attempting to tame the vast wildernessesfull of unfamiliar creatures in what to them was the new and very strange, evensomewhat frightening continent of North America, rural workers such aslumberjacks and loggers would often spend appreciable periods of time away fromtheir families and homesteads.

Consequently, for company and to keepsafe, they would bond together by gathering around fires in their campsites atnight, deep within the dark, forbidding forests, and while away the hours bytelling tall tales to amuse and play-scare each other, seeing who could spinthe most outlandish, spine-chilling yarns, full of daring feats and terrifyingmonsters – the latter often being inspired by sightings and sounds of what tothem were still very mysterious, potentially dangerous native creatures inhabitingthis immense New World.

A1932 hodag-depicting commemorative medallion from Rhinelander (public domain)

A1932 hodag-depicting commemorative medallion from Rhinelander (public domain)

These largely made-up monstrositiesbecame known collectively as 'Fierce Critters', and took many different forms.Some were fantastical mammals, birds, reptiles, or amphibians, others werecolossal fishes, creepy-crawlies, or totally bizarre unclassifiables. Today (whichjust so happens to be ShukerNature's 15th anniversary!), I amdocumenting possibly the most famous one of all, Wisconsin's truly horrific,horrible and unequivocally hideous hodag – an allegedly ferocious terror beastthat has long fascinated folklorists and even a few cryptozoologists.

With many Fierce Critters, their originshave been lost in the mists of time, which makes the hodag's history particularlymemorable, in every sense, because this is one whose origin in its modern-dayform is known very specifically, thanks to a certain Eugene Simeon Shepard.

EugeneShepard as a young man (public domain)

EugeneShepard as a young man (public domain)

Born on 22 March 1854 in Old Fort Howard(later renamed Green Bay), Wisconsin, Shepard moved with his family shortlyafterwards to this US state's New London area, where he worked on his father'sfarm for a time after leaving school before moving further afield when hisfather died to work on other, larger farms in wilder, more remote regions. At16, he became an apprentice timber cruiser, in Wisconsin's Northwoods, where helearnt how to assess tracts of forested land for their lumber value.

And it was here, working for yearsalongside the lumberjacks and loggers who did the physical toiling required toconvert the tracts assessed by him into timber, and listening at night to theirhumorous, highly imaginative stories of Fierce Critters, that embryonic visionsof what would become the fearsome hodag in the form by which it is so wellknown today began to stir inside Shepard's singularly inventive mind – a mindthat proved more than capable of outdoing even the lumberjacks and loggers forweaving yarns. In short, Shepard had a serious talent for tall tales, andpractical jokes too, so he decided to put this talent to good, financially-sounduse.

Everthe showman, Eugene Shepard in a cart pulled by a moose (public domain)

Everthe showman, Eugene Shepard in a cart pulled by a moose (public domain)

For although timber cruising had made himrich over the years, Shepard could see that the timber and logging industry,for such a long time a highly profitable one, was now beginning, slowly yetsurely, to die, due in no small way to the wholesale denuding by unceasinglogging of great swathes of land once profusely covered in trees. So if hewanted to stay wealthy, he needed to look elsewhere to make money.

Since 1882, Shepard had lived in theNorthwoods town (now small city) of Rhinelander, within northern Wisconsin'sOneida County, where in addition to timber cruising he had made good moneybuying and selling property, including areas of tree-cleared land for use infarming. Consequently, this is what he saw as his – and Rhinelander's – future,turning the town into a renowned, famous centre for land speculation, propertydevelopment, and farming. But in order for this to succeed, Rhinelander neededto be placed fairly and squarely on the map – the media map, that is. In otherwords, it needed an attraction, one that would serve to draw in from far andwide as many prospective land buyers and farmers interested in settling here aspossible.

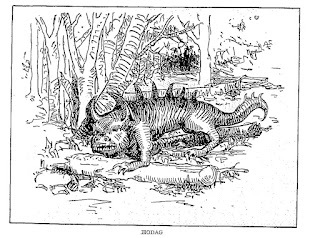

Vintagehodag illustration by Margaret R. Tryon (public domain)

Vintagehodag illustration by Margaret R. Tryon (public domain)

And this was when the enterprisingShepard remembered those folksy fireside lumberjack tales of monsters, inparticular the then only vaguely-defined hodag, and decided to put them togood, practical use – by bringing the hodag to life, literally!

Shepard recalled that the lumberjacks hadclaimed the hodag to be the demonic, vengeful spawn engendered by all the torturedsouls of dead cremated oxen that when alive had been cruelly abused as beastsof burden by these selfsame loggers. Yet apart from stating that like itsbovine progenitors it possessed a fearsome pair of long curved horns, they gavelittle consistent indications of what this malevolent monster actually lookedlike.

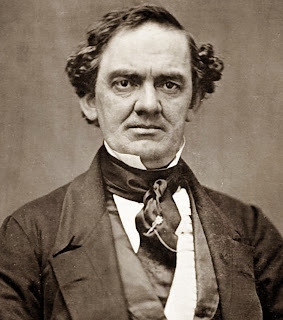

PhineasT. Barnum (public domain)

PhineasT. Barnum (public domain)

Consequently, if he wanted to employ thehodag as his media magnet, Shepard needed to provide it with a well-definedform, which is something that his inordinately creative imagination had littleproblem in conjuring forth. He then needed to transform this newly-renderedmanifestation from a bogey beast of tall tales and yarns into a bona fidephysical, tangible reality – and once again, his entrepreneurial skills soonshowed him the way to achieve this. Not for nothing has Shepard been popularlycompared to that most famous of all 19th-Century American showmenand shysters, the great Phineas T. Barnum himself!

So it was that via a sensational article writtenby himself and published in an October 1893 issue of a Rhinelander newspaperentitled the Near North, Shepardclaimed in his well-honed flair for melodramatic monologues that he and somefellow workers had lately encountered – and killed – an actual hodag inRhinelander's very own forests. He described it as "a terrible brute[that] assumes the strength of an ox, the ferocity of a bear, the cunning of afox and the sagacity of a hindoo [Hindu] snake, and is truly the most fearedanimal the lumbermen come in contact with".

Artisticrepresentation of the hodag (© Richard Svensson)

Artisticrepresentation of the hodag (© Richard Svensson)

As for its physical appearance: Shepardclaimed that the hodag sported the scaly body of a dragon (and breathed firelike one too), plus the head of a huge bull-horned frog, a terrifying elephantineface that snarled with a fanged grin-like grimace, a row of thick curved spinesrunning along its back, four short but sturdy legs with razor-sharp claws ontheir feet, and a lengthy tail that bore spear-like spines at its tip.

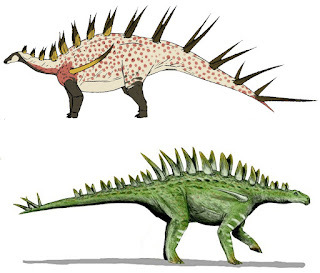

In short, this hodag sounded more than alittle reminiscent of certain non-avian dinosaurs (and was subsequently likenedto such by some chroniclers), in particular certain spine-bearing stegosaurs armedwith thrashing thagomizers, like Kentrosaurus and Huayangosaurus, for instance –overlooking of course its carnivore-consistent fangs, which were conspicuously lackedby these strictly herbivorous prehistoric reptiles!

Top:Kentrosaurus, life restoration (© ConnorAshbridge/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

); Bottom: Huayangosaurus,life restoration (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Top:Kentrosaurus, life restoration (© ConnorAshbridge/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

); Bottom: Huayangosaurus,life restoration (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Speaking of the hodag's meat-eatingproclivities: perhaps the most surprising, offbeat characteristic attributed toit by Shepard was its supposed fondness for devouring an extremely singular,highly specific item of prey – pure-white bulldogs, but only on Sundays! Duringthe remainder of the week, it satiated its hunger pangs by consuming cattle,mud turtles, water snakes, and large freshwater fishes.

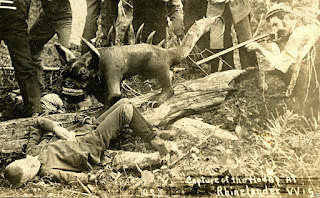

Shepard also added somewhat histrionicallythat this revolting hodag stank of "buzzard meat and skunk perfume"(a distinctive characteristic that he would return to in a subsequenthodag-themed escapade – see later), and that despite shooting it with "heavyrifles and large-bore squirt guns loaded with poisonous water", thecreature withstood all of their efforts to dispatch it. In addition, it had alreadytorn apart the hunting dogs that he and his companions had used to corner itafter having encountered this monster in the forests.

Reconstruction of the hodag based directly upon the specimen in Shepard's 1893 hodag photograph – see below for details re thislatter photo (public domain)

Reconstruction of the hodag based directly upon the specimen in Shepard's 1893 hodag photograph – see below for details re thislatter photo (public domain)

Continuing his febrile fable, Shepardasserted that finally, after hours of fruitless, futile struggle against it, indesperation he and the other men resorted to a very extreme measure – blowingup the hodag using dynamite! Not surprisingly, this certainly worked, reducingit to a mass of charred, unidentifiable remains.

Fortunately (or conveniently, dependingupon your point of view!), however, prior to annihilating their aggressor theyhad been able to photograph it alive – the resulting picture revealing thehodag in all its savage (albeit unexpectedly diminutive) splendour (and despiteits pose being decidedly wooden, in every sense!). This photo was reproducedalongside Shepard's account within his published article, and here it is now inmine:

Shepard's1893 hodag photograph (public domain)

Shepard's1893 hodag photograph (public domain)

Although this hair-raising tale certainlyachieved Shepard's aim of attracting some much-needed publicity for, andinterest in, Rhinelander, he was not content to put aside his pranksterpredilection just yet. Three years later, the hodag reappeared in Rhinelander,courtesy once again of Shepard, who went one stage better this second time roundthan he'd previously done. For instead of a mere photograph and some charredcinders, he now chose to present the genuine item – a living, breathing hodag!

The year 1896 saw the very first OneidaCounty Fair, organized to promote Rhinelander as a prospective location forfuture business and farming developments, and just a few days before it openedanother hodag-themed article by Shepard appeared in the Near North newspaper. Once again it related in stirring fashion howhe and some companions had supposedly encountered a hodag in Rhinelander'sneighbouring forests – but this time they didn't kill it. Instead, aftertrapping it inside its den with stones so that it couldn't escape, theysuccessfully chloroformed the creature, enabling them to capture it alive – andnow, at the forthcoming Oneida County Fair, it would be on display, still verymuch living and breathing, for the fair's visitors to see for themselves!

EugeneShepard's Rhinelander home, with its hodag-holding shed on the right (publicdomain)

EugeneShepard's Rhinelander home, with its hodag-holding shed on the right (publicdomain)

And sure enough, held captive within a shantyyet sturdily-built shed attached to Shepard's own house in Rhinelander, was areal-life hodag – or, to be precise, something that its nervous observers believed to be a real-life hodag.Partially concealed by shadows and a curtain, and held some distance back fromits fee-paying public (who were only permitted to glance upon it through asmall knot-hole), something seemingly resembling Shepard's famous 1893description did indeed lurk, measuring 7.5 ft long, 2.5 ft tall, pitch black incolour and bristly, armed with 12 lengthy spines along its back, moving jerkilyon its short but formidably clawed limbs, and growling. Also, of particularnote, it gave off a putrid stink, just like Shepard had described for it in hisoriginal 1893 article.

Confronted by such a menacing entity, itsvisitors did not stay long enough or approach close enough to obtain a goodview of it, which was just as well, at least as far as Shepard was concerned.For, needless to say, the hodag was a hoax – a large model sculpted from woodenlogs with fine wires attached to make it move. It had been skilfully constructedby Luke Kearney, one of Shepard's friends (who, years later, went on to writethe very informative book The Hodag andOther Tales of the Logging Camps), and was deftly manipulated by Shepard'ssons Claude and Layton, acting like puppeteers (with a hidden dog giving voiceto the supposed hodag's belligerent moans, groans, and growls when prodded by asmall boy). As for its stench, this derived from rank, discarded animal hidesobtained from the local tannery that were used to cover the hodag model'swooden framework.

Artisticreconstruction of Shepard's captive hodag of 1896, in Wide World Magazine, May 1915 (public domain)

Artisticreconstruction of Shepard's captive hodag of 1896, in Wide World Magazine, May 1915 (public domain)

Whether Shepard would have ever owned upof his own volition to committing this fraud, or whether he would havecontinued with it, will never be known, because in the event he had no optionbut to confess. For he learned that some scientists from the SmithsonianInstitution were so intrigued by media reports of this astonishing animal thatthey were planning to visit Rhinelander and observe it directly. The game wasdefinitely over, and so was the hodag marionette, which performed no more.

Nevertheless, Shepard's promotion-servingpranks had achieved all that he had hoped for, and more. Rhinelander was indeedon the map now, and the hodag duly entered local folklore on a permanent basis.Yet ironically, Shepard's success actually worked against him on a personallevel, because his hodag hoaxes turned him into an infamous, despised figurelocally, who became shunned both within and even beyond his Rhinelanderhomeland. Tragically, on 26 March 1923 aged 69, Shepard died alone, of kidneyfailure, still estranged from his family and former friends. In modern times,conversely, his reputation has been largely regained and his contributions toRhinelander's thriving success repatriated, due in no small way to the hodag'sfame and lasting legacy in Rhinelander, and Wisconsin in general, for thatmatter.

EugeneShepard in c.1915 (public domain)

EugeneShepard in c.1915 (public domain)

Indeed, like all the best local legends,down through the decades since Shepard's time the hodag's mythology hascontinued to evolve and expand. Nowadays, for example, several different typesof hodag are recognized.

These include the self-explanatoryshovel-nosed hodag, which also has longer limbs than the standard variety, andthe highly-specialised cave-dwelling hodag, distinguished by its complement ofthree eyes, enabling it to see clearly within its realm's stygian darkness.

Shovel-nosedhodag (top) and cave hodag (bottom) (© Richard Svensson)

Shovel-nosedhodag (top) and cave hodag (bottom) (© Richard Svensson)

Also, some of the more free-thinkingmembers of today's cryptozoological community actually harbor suspicions thatthe hodag may be more than a fanciful fabrication.

Such speculation posits that there could infact be a real, still-undiscovered animal species evading scientific detectionamid the more remote regions of Wisconsin that inspired Shepard's morphology musingswhen creating his hoax specimens.

TraditionalNative American pictograph of Mishibeshu at Lake Superior Provincial Park (© DGordon E Robertson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

TraditionalNative American pictograph of Mishibeshu at Lake Superior Provincial Park (© DGordon E Robertson/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

It has even been tentatively linked to asuperficially similar-looking mythical entity known as Mishipeshu ('greatlynx'), also dubbed the water panther, and traditionally claimed by a number ofdifferent indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and Great Lakes regionto inhabit Lake Superior.

Oral descriptions as well as petroglyphs ofMishipeshu that date back as far as 400 years ago portray a lengthy reptilianwater monster covered with scales but sporting a pair of large cow-like hornson its head, plus a snarling feline face with prominent fangs, four stoutclawed limbs, and a series of long spines running down its back and lengthy tail.Might Shepard have conceivably been inspired by folk-stories of this legendaryaquatic beast when fleshing out his hodag specimens?

Imageof water panther, from the National Museum of the American Indian, GeorgeGustav Heye Center library (public domain)

Imageof water panther, from the National Museum of the American Indian, GeorgeGustav Heye Center library (public domain)

Notwithstanding any such hypothetical real-lifeor legendary water-dwelling hodag precursors, what is unquestionably a fact isthat today Wisconsin's most exceptional, unexpected representative iscommemorated in all manner of different cultural ways here. Several Rhinelanderorganizations and businesses incorporate the hodag in their formal names, forinstance, plus this city's annual music festival is known officially as theHodag County Festival, its high school embraces the hodag as its officialmascot, and many shops here sell a wide range of hodag souvenirs, includingfriendly hodag cuddly toys.

In autumn 1959, the then-Senator John F.Kennedy was even presented with a miniature hodag figurine when he visitedRhinelander during a political campaign, this unusual gift impressing and delightinghim so much that he placed it on display at his home afterwards for guests totalk about. He also specifically referred to it himself in a subsequent pressinterview (Rhinelander Daily News, 16July 1960).

Fibre-glasshodag statue in front of the Rhinelander Area Chamber of Commerce (© redlegsfan21/Wikipedia–

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Fibre-glasshodag statue in front of the Rhinelander Area Chamber of Commerce (© redlegsfan21/Wikipedia–

CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

)

Most impressive of all, however, are anumber of spectacular hodag statues dotted around this city. Perhaps the mostfamous one is the larger than life-size, bright green, fibre-glass examplecreated by local artist Tracy Goberville that stands proudly in the grounds of theRhinelander Area Chamber of Commerce, with another two on display atRhinelander's Ice Arena (one of which even blows out smoke from its nostrils asits red eyes light up!).

These and other eyecatching replicahodags attract countless tourists visiting Rhinelander every year. Were he hereto see them himself, I feel certain that Eugene Shepard would have approved!

'AllEyes on the Hodag' statue by artist Linda Gilbert-Ferzatta in Rhinelander (© CoreyCoyle/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

'AllEyes on the Hodag' statue by artist Linda Gilbert-Ferzatta in Rhinelander (© CoreyCoyle/Wikipedia –

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Last, but by no means least: from whereis the name 'hodag' derived? It certainly didn't originate with Shepard,because this term existed long before his hoax specimens did. In fact, there isno common consensus as to its etymological origin.

However, the most popular explanation onoffer, and favoured by leading hodag historian Kurt Kortenhof (author of the definitive2006 book Long Live the Hodag: The Lifeand Legacy of Eugene Simeon Shepard) is that 'hodag' derives fromlumberjack slang for one of the implements that they used in their work. Thetwo likeliest possibilities are a type of heavy-duty hoe known technically as agrub hoe, or a type of flat-faced pickaxe known technically as a maddox. So nowwe know…sort of!

Top:Photograph of a re-creation of Shepard's 1893 hodag capture scene for a 1950 Rhinelanderpageant (public domain); Bottom: Vintage picture postcard presenting Shepard's 1893hodag photograph in close-up (public domain)

Top:Photograph of a re-creation of Shepard's 1893 hodag capture scene for a 1950 Rhinelanderpageant (public domain); Bottom: Vintage picture postcard presenting Shepard's 1893hodag photograph in close-up (public domain)

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers