Free Will: A Conceptual Framework

by John Danaher

Free will, if it exists, is a property of agency. It is something that agents, in virtue of their constitution, can exhibit that non-agents cannot. Furthermore, free will may be the most morally, spiritually, and existentially important property of human agency.

It has occurred to me that I might like to look at some recent papers on the topic of free will on this blog. Those papers tend to assume that the reader is familiar with the ins and outs of the contemporary debate on this issue. I don’t like to make those kinds of assumptions, partly because you never know who might be reading a blog, and partly because reacquainting oneself with the basics of an issue is always worthwhile.

This post offers a conceptual framework for analysing the contemporary debate on free will. The framework comes in three sections. The first section examines the nature of free will as a property of agency; the second section considers the intellectual significance of the debate; and the third section outlines some of the positions one can take up in this debate.

1. The Nature of Free Will

No one would deny that the term “free will” is ambiguous. A lot of conceptual baggage has been attached to those two simple words over the years. This is one reason why the debate over free will (even in the philosophical literature) can be so frustrating: different authors apply different meanings to the term and often end up talking past on another.

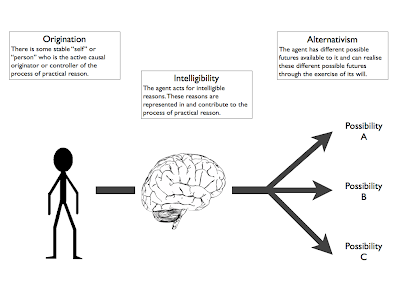

In an effort to cut through some of that confusion, I like to appeal to a model of free will that I first came across in Henrik Walter’s book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will[image error]. Walter’s contention is that when we talk about the property of free will, we are talking about a decision-making capacity with three components:

(i) Alternativism: this is the capacity to (meaningfully) choose between different possible futures. In other words, if X must choose whether to eat an apple or an orange, and if X chooses the orange, it must still be possible for X to choose the apple.(ii) Intelligibility: this is the capacity to act from intelligible reasons. In other words, X does not simply choose among possibilities at random, X chooses in accordance with reasons, intentions, desires and beliefs.(iii) Origination: this is the capacity to be the originator of actions. In other words, X is not simply a passive receptacle through which external causal forces exert themselves but is, in some sense, the active originator of causal forces.

There are two main advantages to thinking about free will in this way. First, by focusing on three elements, this model helps to avoid the pitfalls associated with thinking about only one of the elements. For example, most discussions of free will are preoccupied with the concept of alternativism. But a popular objection to this preoccupation is that an agent with alternativism and nothing else might amount to little more than a random choice-generator. This would not be the kind of morally salient choice with which we are concerned. The extra ingredients of intelligibility and originations are needed for that.

Second, this model is flexible enough to encompass the diversity of positions that exist on the nature of free will. The flexibility stems from the fact that each of the three components can be subjected to strong, moderate or weak interpretations.

For example, a strong version of alternativism might contend that the agent must have been able to realise different possible futures in the exact same circumstances as obtained at the moment of their original decision. A weaker version might argue that sensitivity to changes in circumstances is all that is required. In future entries we will consider the respective merits of such interpretations.

Because one can have different interpretations of the three components, one can think of this model as describing three dimensions along which different theories of free will can vary. It might be the case that weak interpretations do not deserve the label “free will”, but this is something that can be worked out after the different positions have been described.

2. Intellectual Significance

Why do people bother writing and debating the concept of free will? What’s at stake in this debate? I suggest that there are three separate issues to worry about (I think I’m taking this from something Patricia Churchland said, but I can’t be too sure):

Discussions of free will tend to blend these issues in different ways. This is understandable since how you resolve one of them will affect how you resolve the others. Nonetheless, it is worth keeping them distinct at the outset.

3. Different Positions on Free Will

After over two thousand years of sustained philosophical debate, one can imagine that numerous stances and positions have been identified on both the nature of free will and the moral and existential issues associated with it. It would be difficult to do justice to all of these positions, but thankfully most of the conversation tends to gravitate towards the following:

So there you have it, a conceptual framework for discussing free will. I will refer back to this post in future entries on this issue.

________________________________________________________________________

* “Positive” is meant here in the sense of “believes it to be true” and not “believes it to be a good or desirable thing”.

Note. This is just an introduction to the issue. Danaher explores the issue in depth here.)

This work by John Danaher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.