Still Eager to Hear About Sacco and Vanzetti, at Whitman Public Library

The program room at Whitman, Mass. Public Library filled steadily, until more chairs had to be separated from a file a pile in the far corner of the room and placed on the floor to accommodate the audience for what librarian Barbara Bryant called "the best-attended author talk we have ever had!"

The talk about Sacco and Vanzetti was her idea, her invitation. I hadn't given a talk about the two Italian immigrants falsely accused of murder and robbery back in 1920, and ultimately executed by the state of Massachusetts seven years later despite worldwide protests -- for half a dozen years. I gave a bunch of them, mostly in libraries, after the publication of my novel based on the case, "Suosso's Lane."

The audience that filled the Whitman library program room was almost uniformly of an age to know that we're all part of history now.

This talk was about the facts of the case, not directly about my book. The book is fact-based, but goes beyond the historical record to invent a contemporary (wholly fictional) investigation to turn up some new evidence about the old case. Those talks were fun, but a little fraught -- I was hoping back then to sell books.

To prepare for this talk, I had to go back to my notes and printouts for those talks from seven years ago and reacquaint myself with what I used to know well enough to share by memory with an audience, Facts, dates, places, names were particularly important, indeed essential, because this was a talk about the case, its history, rather than about the book.

Here's what I told them, the good people of Whitman, about the Sacco-Vanzetti case, the international affair that exposed America's prejudice against immigrants, particularly those from Italy.

By Robert Knox

These are difficult days in American politics – perhaps difficultdays in America, period. But times were tough a hundred years ago as well,especially for immigrants and for civil liberties – i.e. constitutionalprotection of free speech and other basic rights.

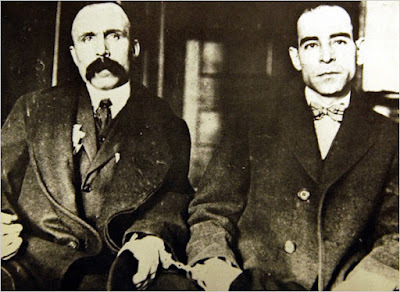

A little more than a hundred years ago, on April 15, 1920, thecrime took place that began the notorious Sacco and Vanzetti case – an Americanscandal of injustice that became an international cause – in which two Italianimmigrants who professed anarchist beliefs were accused without a shred of realevidence of committing a heinous crime, tried in a prejudiced courtroom,convicted by a nativist jury – that is to say, all male American citizens in a timewhen only men could vote – and eventually executed 7 years later, by which timetheir case had become an international cause de celebre. (They were famousnames worldwide, everybody knew about the case; everybody worldwide knew theywere victims of injustice.)

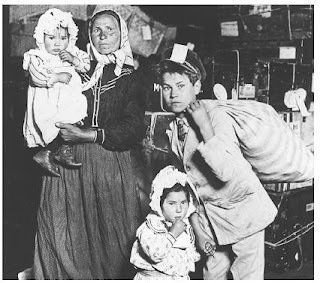

Immigration, always an essential part of the American story, lookeda lot different in the early 20th century. Immigrants came fromEurope – not from Mexico, Central America, Asia, the Caribbean, Africa or theMiddle East, as they do today. They came at first from England, Scotland, Ireland,Germany, Scandinavia, mostly northern European countries. But from around 1880 andinto the 1920’s, in greater numbers than had ever been seen, they came fromsouthern and eastern Europe. From Poland, Russia, the Balkans, Portugal,Turkey, and – the single greatest number – from Italy. For those who came from Italy,the cause was almost always purely economic. Disasters weakened the economicbase of Southern Italy: drought, crop disease, the collapse of traditionalfisheries and the lumber industry. At the same time advances in maritimetransportation made it easier, and less expensive, to cross the ocean. Many Italianmen crossed the ocean to work in seasonal industries and then return home withtheir earnings year after year. But many others, including women and children–whole families – chose to come and stay.

During those peak decades, 1880-1920, national prejudices grew asnumbers of immigrants did. Some towns or companies made it clear when they werehiring more workers that they did not intend to hire Italians.

Two immigrants: Bartolomeo Vanzetti arrived in America in1908 as a young man of 20 to “put an ocean between my mother’s death” and therest of his life, he said…. Unlike most, he did not come for economic reasons.His father was a wealthy farmer in northern Piemonte Italy (in Villafilletto) whowanted Bartolomeo to learn to run his businesses. He sent him to the city tolearn to be a pastry chef and help the family business that way. Bartolomeofound pastry-making to be factory work, piece-work, a miserable business inconditions that nearly killed him. He became seriously ill with a breathingdifficulty, was sent home, where his mother devoted herself to nursing him backto health. Then she developed cancer and died after months of suffering. Herdevoted son thought that her efforts to save him weakened her. Wishing toseparate his future from a painful past – he had a deep relationship with hismother, but a poor one with his father, he decided to go to America, which hethought of as “the land of the free.” No big divides between social classes; nooppressive national church.

Vanzetti was not an anarchist when he arrived. His life in the USled him to that philosophy. He later told reporter about the early years, “Iwas a Dago to be worked to death [a pejorative]…. We lived in a shanty, wherethe Italians work and live like a beast…” Like other day laborers, he is forcedto follow the availability of work, a trade he called “pick and shovel.” Afterfive years mostly in New York, rumors of work brought him to Mass., andeventually to Plymouth, where he boarded with the Brini family who came fromhis region in Italy, and who lived in North Plymouth, the immigrant section oftown. [this is how I got interested in the story...working for communitynewspaper publisher based in Plymouth] He became close to the family’schildren. He called Beltrando Brini his “spiritual son.” Recorded interviewscollected and published later show V. to be kind, courteous to women, gentleand loving to children; V was a talker, a thinker, a dreamer, a reader. Among thebooks he owned was “the life of Jesus Christ” by Ernest Renan. Anarchism becamehis religion; its ideals gave meaning to his life… Among his jobs was workingon repairs to Plymouth harbor.

Nicola Sacco was born in the town of Toremaggiore (SE of Italy) andemigrated to US in 1908 at age 17. He loved machinery. He emigrated with hisbrother Sabino, and when his brother returned to Italy in 1909 and he was leftalone in the United States, he began to take lessons on shoe-trimming andbecame an excellent shoe trimmer. He was a skilled worker; made a good living. Hemarried his wife Rosa, when he was 21, she 17, and first child was born in1913.

He found settled work in a shoe factory in Stoughton, Massachusetts;he developed a strong relationship with the owner, the son of an Irishimmigrant. He made a good living because he was so good at what he did. A shoetrimmer is piece work. He could make a day’s pay in a few hours. He was alsoattracted to the cause of labor, and participated in strikes. …Sacco helpedwith the defense of Arturo Giovannitti, an Italian labor organizer -- one ofthe principal organizers of the famous 1912 Lawrence textile strike -- anItalian immigrant who had been arrested on a dubious murder charge. Itwas one of his first radical activities.

A definition: The word “anarchy” means ‘no authority.’ [From theGreek: ‘a’ means not; archon is a ruler] It doesn’t mean chaos. It means livingwith no governing state, no political or “established” religious institutions.No rich; no poor… V. called anarchy “the beautiful idea.” People, he believed,would live happily and survive materially by forming voluntary cooperatives. Sharingresources. Recognizing the needs of others as important as one’s own.

For anarchists like V and S and for many other social critics, thefundamental issue in this stage of western civilization was “rich versus poor”.…today we call that “the distribution of wealth.”

Believing that workers were oppressed by the capitalist system, by theowning of property, anarchists like Sacco and Vanzetti – both became disciplesof the anarchist theorist Luigi Galleani (V. called him my ‘master’) –supported and took part in strikes. Though he did not work there, Vanzetti tookpart in the 1916 strike against the Plymouth Cordage Company, a largeropemaking business. WWI created a great demand for American resources such as cordage,but war-driven inflation ate up workers’ earnings.

When America joined the war in 1917 (3 yrs after it began), the actforced political radicals to choose: participate or not? Anarchists opposed allwar; they opposed the draft; they opposed governments.

Sacco, who supported strikes by his physicalpresence – strikes were often street battles – also became a disciple of Galleani. He began attending weekly meetings of an anarchist group in 1913 and subscribedto Cronaca Sovversiva (“Subversive Chronicles”), as didVanzetti, an anarchist newspaper published by Galleani in Italian. He becamea devotee of Galleani and in the next several years wrote for the paper, donatedand solicited funds for anarchist activities, as well as support his family.

So the two men have much in common, aworld view, an allegiance to the views of a powerful theorist, or ideologue inGalleani. A strong commitment to social change. They’re the kind of people thebusiness and political establishment hate and fear. They want change. Asanarchists see it (or ‘radicals’ generally), the ‘establishment’ hates change;it wants to preserve the status quo. The owners and the politicians are rich;they don’t care if you’re poor.

The two meet at activities held in opposition tothe war. Then, in 1917, both join a group of men leaving home to travel toMexico and live under pseudonyms in order to avoid the draft.

The Mexico experiment lasts a few months. No jobs;no money. Then both men go ‘home.’ Sacco returns to his young family, in Stoughton,Massachusetts, where he worked for a shoemaker, who valued him so highly hegave him management responsibilities and paid him to keep an eye on the factoryafter hours. Vanzetti goes back to Plymouth; has to find a new place to board, theBrini family doesn’t have room for him any more. He boards with a widow a fewstreets over in North Plymouth. He also finds a new to make a living; sellingfish, door to door, among the immigrant community.

OK, now comes the heavy political stuff.

During a period of anti-radical andanti-foreigner hysteria known as “The Red Scare,” [ask yourself if this was inyour American History class] a well-organized criminal gang carried out abrazen daylight robbery in Braintree, Mass. The robbers stole a shoe factorypayroll and shot and killed the paymaster and his guard at point-blank range.

We'll come back to the crime, but first we have to talk about the Red Scare of 1919–1920 — a time of nationalparanoia in which thousands of immigrants were detained without dueprocess of law.

After the US entered World War I in 1917, Congresspassed laws to suppress all criticism of government’s decision to join theongoing European slaughter or any means the government chose (such as the draft) to conduct the war.Anti-war critics were prosecuted, the non-citizens among them deported to theirnative countries. (For comparison, imagine that response to war protests andcriticism of the government during the Vietnam War era.)

When Galleani was deported to Italy, some of his followers‘declared war’ on the government – arguing that the government had already beenmaking war on them -- on the institutions that suppressed their publications,broke up rallies of war critics, and used the courts to suppress their FirstAmendment freedoms of expression. In response, these followers – some of themmembers of the same ‘gruppo’ that Sacco and Vanzetti belonged to -- sent bombs through themail and placed them at the homes of their ‘enemies’ in government and bigbusiness. These "Anarchist Fighters" were self-declared enemies of the state.

In his recent book “American Midnight,” historian Adam Hochschilddetailed the US government’s outrageous violations of war critics’Constitutional rights – and the rights of Americans in general. Thousands ofimmigrants were rounded up in mass raids, declared ‘disloyal’ and sentenced todeportation before a single federal judge stepped in to overturn decisions madewithout due process of law.

His legally prescribed role was to make sure "due process" had been followed before he approved the deportation orders. He refused: dueprocess had not been followed.

A crackdown on labor organization was taking place as well: Union meetings werebroken up by local and government police; speakers, and simple participants,dragged off to jail… A lawless war was declared on members of the most active labororganization of the time, the IWW, the Industrial Workers of the World, knownas Wobblies. Private industry, especially 'big business' supported the war. There was lots of money to be made from it. Organized labor -- unions -- cut into their profits. Now that the US was at war, big business wanted union organizers to be seen as traitors.

Wartime deportations included the nation's most famous critics of capitalism, among them Emma Goldman, a Russian immigrant, radical, anarchist, and America’s most popular lecturer. She traveled wholecountry, drawing audiences everywhere and speaking on a wide range of social and political subjects.

Eugene V. Debs, not an immigrant but a Socialist party candidate who received almost a million votes for President in 1912, was jailed for opposing the decision to go to war.

Mobs of what were called“Super-Americans” physically attacked and broke up meetings of war critics, draft critics, and labor organizers. Enforcing wartime restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly required the creation of the first federalpolice force, called the Radical Division of the Department of Justice; it later became theInvestigation Bureau; finally the FBI, its principal duty from the very beginning being to ferret out and suppress 'subversion' by labor organizers or 'radical' critics of the status quo. J. Edgar Hoover, in his 20s was there from the Red Scare to the Civil Rights era when his agents were harassing leaders such MLK.

After the government suppressed Galleani's network, destroyed his printing press, burned his writings and tried and deported the maestro himself back to Italy, his followers decided they had to fight back. Going underground, hiding their identities, they formed the "Anarchist Fighters" and mailed bombs to the houses of federal judges, police chiefs and prominentcapitalists, "terrorist" style, in revenge for the 'war' the American government had been waging on them. Famously, June 2, 1919, bombings in major cities such as Washington DC and Boston shook the nation. Top of the page was the bomb that exploded on the frontsteps of the Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s house in DC, destroying most of thehouse but not harming the family. Other buildings were destroyed, but almost no onewas seriously hurt, except for the anarchist who blew himself up when the bomb he was planting at Palmer's house went off prematurely. Remarkably, we know his name, Carlo Valdinocci, an Anarchist Fighter and follower of Galleani. Sacco and Vanzetti would have known him.

Thesebombings lead to the "Palmer raids," as they are known, in late 1919, when federal agents and vigilantesconduct major raids in big cities rounding up supposed radicals and thousands ofimmigrants – lots of Russians, since after the Russian Revolution ‘communism’ is now perceived as a majorthreat. Detainees are roughed up and kept in poor conditions. Congress passes a law making itillegal to be a member of an anarchist organization.

Federal agents declare they will find those responsible for the bombings, but get nowhere. After almost a year, the feds arrest Andrea Salsedo, a member of the Galleani network; a printer, he made the leaflets denouncing the government the ‘Anarchist Fighters’ include in their bombs. He’s questioned, tortured, and held without charges inpolice office building in New York City. He smuggles out a letter to Vanzetti, asking for help, and Vanzetti heads to New York, though it's unclear what he can hope to accomplish. But before he can get to see him, Salsedo dies falling out a window of a police building. The cops say it was a suicide; other anarchists say he was pushed.

But the crackdown on 'radicals' following the Anarchist Fighters' bombings creates the hostile law-enforcement atmosphere in which any critic of the government, the war, or wartime profiteering by Big Business is treated. This politically tense atmosphere may explain why local and state police in Massachusetts tried hard to convince themselves that 'radicals' might be responsible for a shoe factory robbery in Braintree.

The Crime:

In a well-planned criminal enterprise, a gang carried out a brazen daylight robbery inBraintree, Mass., on April 15, 1920. The robbers stole a shoe factory payroll and shot and killedthe paymaster and his guard at point-blank range.

Some days later, in a completely unrelated matter, members of Sacco and Vanzetti's "Gruppo" decided that in view of the government's sweeping attack on radicals and immigrants following the Anarchist Fighters' bombings, they should hide evidence linking them to Galleani, such as copies of his journal "Cronaca Sovversiva." …The Gruppo decides to send some of its members to collect anarchist lit from other members and hide it. Sacco and Vanzetti and two other group members decide to retrieve a comrade’s car left at the home of a mechanic inBridgewater. Police have staked out the car, on the grounds that that Bridgewater is somewhat near Braintree (not really) and since some anarchists have taken to planting bombs, maybe they also commit robberies -- a notion that, a century later, makes no more sense now than it did at the time. Cops tell the mechanic to call them at once if anybody comes for the car.

Four Gruppo members, two riding a motorcycle, arrive at the Bridgewater mechanic's home one evening to retrieve the car, which they plan to use to round up anarchist literature from other group members. The mechanic stalls, then tells the visitors that the car isn't ready to drive yet. His visitors shrug, decide it's now too late to make their rounds without a car. The two guys get back on the bike for the ride home. Sacco and Vanzetti take off on foot to the nearest streetcar stop. Meanwhile the mechanic's wife has called the Bridgewater police to say four "foreign" guys came looking for the car.

State police put out the word to local cops to look for foreign-looking guys leaving Bridgewater. Streetcars are stopped, and two men with foreign accents are taken off a streetcar at gunpoint, hauled to a police station and interrogated. After the two men freely admit to being anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti are charged with robbery and murder, despite any evidence linking themto the crime. They were charged, police would later say, because they liedabout what they were doing on the night of their arrest. They said they were visiting a friend. And because they werecarrying weapons. Quick fact check: This is America! lots of peoplecarry weapons – it’s legal. Vanzetti told the police they were carrying guns "because there were a lot of dangerous people around." Clearly, though, they came under suspicion largely because they werefriends of another anarchist who owned the car. It’s hard to find a clearercase of “guilt by association.”

The Trial

Since police and prosecutors lacked any substantial evidenceagainst the two radicals, both of whom had witnesses for their whereabouts onthe date of the crime, they went about creating it. Among the many shoe factoryworkers who managed split-second glimpses of the crime from factory windows,the state found a few whom they could pressure, or threaten, into testifyingthat they recognized the defendants. In the best of circumstances eye-witnesstestimony to the brief, violent or otherwise criminal acts of strangers ishighly unreliable. The overwhelming majority of factory workers interviewedeither said the accused were not the robbers, or they could not make anidentification based on what they had seen.

Since police and prosecutors lacked any substantial evidenceagainst the two radicals, both of whom had witnesses for their whereabouts onthe date of the crime, they went about creating it. Among the many shoe factoryworkers who managed split-second glimpses of the crime from factory windows,the state found a few whom they could pressure, or threaten, into testifyingthat they recognized the defendants. In the best of circumstances eye-witnesstestimony to the brief, violent or otherwise criminal acts of strangers ishighly unreliable. The overwhelming majority of factory workers interviewedeither said the accused were not the robbers, or they could not make anidentification based on what they had seen.

When the case went to trial, ballistic experts disagreed overwhether a bullet removed from one of the victim’s body could have been fired bySacco’s gun. Recent re-examinations of both the ballistics and autopsy evidencesuggest that the state fired a bullet from Sacco’s gun and subbed it for one ofthe bullets surgically removed from a victim’s body. Since the state failed tomaintain a secure chain of evidence, the case’s physical evidence wascontaminated.

The trial’s native-born, male jurors were themselves hardlyunbiased. After the trial, the jury foreman said he didn’t care whether thedefendants were guilty or not, saying “they should hang them all.” Itwas clear who was meant by this ‘them’ — foreigners with political beliefs thatnative-born citizens found threatening.

And trial judge Webster Thayer made his own bias clear in a widelyreported comment to a college classmate, at an alumni reunion, after passingsentence: “Did you see what I did to those anarchist bastards?”

The defendants' attorney, a respected labor lawyer naturally appealed, beginning a legal process that lasted seven years. Appeal hearings were delayed, postponed, rescheduled for a host of reasons -- so-called prosecution witnesses had left the state and needed to be tracked down. Expert witnesses were ill andcould not attend until recovery. The judge was ill for a year. The appeals court judge was ill, and then needed a vacation. When the state's supreme judiciary court finally rejected the defense's appeal, only then could Webster Thayer pronounce sentence: death in the electric chair.

The sentencing brought widespread public protests, both in this country and abroad, to a boil. A typical newspaper headline from 1927 captured the universality of working class and progressive condemnation of the court's decision:

"Protests and demonstrations and strikesall over the United States, in Germany, England Australia, Switzerland,Paraguay, Mexico, on every continent except Antarctica."

In Paris, a protest gathering drew a reported one million people.

In Paris, a protest gathering drew a reported one million people. A who’s who of prominent figuresfrom different walks of life expressed support for Sacco and Vanzetti eitherpublicly or privately. Writers Dorothy Parker and Edna St. Vincent Millay

showed up to demonstrations. Benito Mussolini, then prime minister of Italy,explored potential avenues for requesting a commutation of the sentence.Various others, from Albert Einstein to George Bernard Shaw to Marie Curie,signed petitions directed toward Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller or U.S.President Calvin Coolidge.

The defendants' attorneys made a final appeal for clemency to the governor of the state. Unhappily, the overseas attention paid to the case may have worked against the defendants. Governor Alvan Fuller, a Republican, visited them in prison while weighing an appeal and was impressed by Vanzetti's personality, remarking: “what an attractive men.”

Vanzetti had used jail time to improve his English. He wrote letters to supporters, and a few memoirs. Fuller said he considered granting a pardon but, one associate explained, "He felt that worldwide interest in the case proved thatthere was a conspiracy against the United States."

Their execution, after several stays ofexecution by Fuller kept the case on the front pages in thesummer of 1927, drew international outrage, including violent demonstrations in France and in some other European countries. Thousands of people gathered the night ofthe execution, Aug. 23, 1927, many of them on the Boston Common, in a vigil…dispersing aftermidnight in sorrow after word passed that the men were dead.

The executions also led to a huge public funeral march through thecity of Boston regarded as the largest public gathering in the city until theRed Sox World Series victory parade in 2004, with the crowd estimated bynewspapers at 200,000.

FINAL WORDS

I will give the lastwords to the two principals in this story:

"At his trial Sacco said that life in the U.S. is good forpeople with money but it’s not good for the working and the laboring class, andat his sentencing, he said, 'I know this sentencing will be between twoclasses, the rich class and the working class, and there will always becollision between one and the other.'"

Vanzetti said theirdeaths would be a worthy sacrifice. He said he mkight have spent his lifetalking to sad men on street corners, winning no change or improvements: afailure.

But “Now we are not a failure. This is our career and ourtriumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, forjustice, for man’s understanding of man as we now do by dying. Our words, ourlives, our pains—nothing! The taking of our lives—lives of a good shoemaker anda poor fish peddler—all! That last moment belongs to us—that agony is ourtriumph.”