Mystifying and Dangerous

As any regular reader of this blog already knows, the very first D&D module I ever owned was In Search of the Unknown. One of the consequences of this is that, for good and for ill, it very soon became my mental model for what a dungeon should be like. More specifically, module B1 instilled in me an early love of tricks, traps, and secrets as integral elements of a dungeon. Nearly every room is Quasqueton contains one of these elements, whether they take the form of a forest of weird fungi, a set of false stairs, or the famous room of pools.

As any regular reader of this blog already knows, the very first D&D module I ever owned was In Search of the Unknown. One of the consequences of this is that, for good and for ill, it very soon became my mental model for what a dungeon should be like. More specifically, module B1 instilled in me an early love of tricks, traps, and secrets as integral elements of a dungeon. Nearly every room is Quasqueton contains one of these elements, whether they take the form of a forest of weird fungi, a set of false stairs, or the famous room of pools. The most important thing for me, then and now, is that the dungeon includes lots of things for the characters – and their players – to fiddle with and puzzle over. That's one of the great appeals of dungeon delving: trying to figure it out. Of course, it helps immensely when figuring things out brings with it a tangible benefit, like treasure or knowledge. There needs to be some kind of incentive to making the extra effort, just as there needs to be some kind of risk to balance it.

Volume 3 of Original Dungeons & Dragons contains the earliest advice to the referee in designing a dungeon. One of the most memorable bits of that advice is the following:

Volume 3 of Original Dungeons & Dragons contains the earliest advice to the referee in designing a dungeon. One of the most memorable bits of that advice is the following:The fear of "death", its risk each time, is one of the most stimulating parts of the game. It therefore behooves the campaign referee to include as many mystifying and dangerous areas as is consistent with a reasonable chance of survival (remembering that the monster population already threatens this survival).That comes very close to encapsulating the lessons I drew from reading In Search of the Unknown all those years ago. If you look at many of the earliest published dungeons, whether from TSR, Judges Guild, or appearing in the pages of Dragon and other RPG periodicals, you'll see they almost always include enigmas, puzzles, and traps of varying degrees of fiendishness. Indeed, I'd go so far as to suggest that these elements are integral to what a dungeon is.

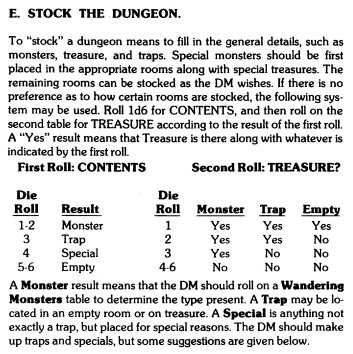

Tom Moldvay's 1981 revision of the D&D Basic Set provides step-by-step instructions to the novice referee on how to create and stock a dungeon. If one follows those steps faithfully, approximately one-third of all dungeon rooms will contain either a trap or a "special," Moldvay's version of OD&D's "tricks." Specials aren't necessarily dangerous, but they're definitely odd and unusual. Moldvay gives several examples of specials, ranging from a "moaning room or corridor" to a "talking statue" to a "shifting block to close off corridor."

Tom Moldvay's 1981 revision of the D&D Basic Set provides step-by-step instructions to the novice referee on how to create and stock a dungeon. If one follows those steps faithfully, approximately one-third of all dungeon rooms will contain either a trap or a "special," Moldvay's version of OD&D's "tricks." Specials aren't necessarily dangerous, but they're definitely odd and unusual. Moldvay gives several examples of specials, ranging from a "moaning room or corridor" to a "talking statue" to a "shifting block to close off corridor." I adore these kinds of dungeon elements. Anything that gets the players thinking about the dungeon, even simply as a play space, greatly appeals to my sensibilities. Old school D&D fans often say that the hobby was born in the megadungeon and, while there's much truth to that, I think it's just as true to say that the hobby was born in the challenge dungeon, which is to say, a space where the players matched wits against the referee in figuring out his puzzles and overcoming the trials he set before them. My appreciation for this style of play may explain why I've never hated The Tomb of Horrors as so many others have.

Over the years, I get the impression that tricks, traps, and secrets of this sort have become a lot less popular among players of Dungeons & Dragons, but perhaps that's mistaken. What I can say with some certainty is that, fairly early on in their existence, video games, especially since the advent of the personal computer, have taken up the idea of trials and secrets in a way that I find very reminiscent of early D&D challenge dungeons. That shouldn't come as a surprise, of course, since D&D's influence on the development of video games – and not just of the RPG genre – is immense.

Over the years, I get the impression that tricks, traps, and secrets of this sort have become a lot less popular among players of Dungeons & Dragons, but perhaps that's mistaken. What I can say with some certainty is that, fairly early on in their existence, video games, especially since the advent of the personal computer, have taken up the idea of trials and secrets in a way that I find very reminiscent of early D&D challenge dungeons. That shouldn't come as a surprise, of course, since D&D's influence on the development of video games – and not just of the RPG genre – is immense. Still, I can't help but feel that dungeons are at their most fun for me when they include lots of riddle-spouting statues, giant chessboards, green devil faces, and deviously hidden secret rooms. A dungeon without such things will soon get boring and will never become a campaign tent pole of the sort that encourages return visits. I can't tell you how many hours I've poured into certain video games over the years trying to beat exceedingly difficult encounters or trying to locate some hidden chamber, often for very little in-game reward. There's no reason dungeons can't be like that, too.

Published on December 03, 2023 21:00

No comments have been added yet.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers

James Maliszewski isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.