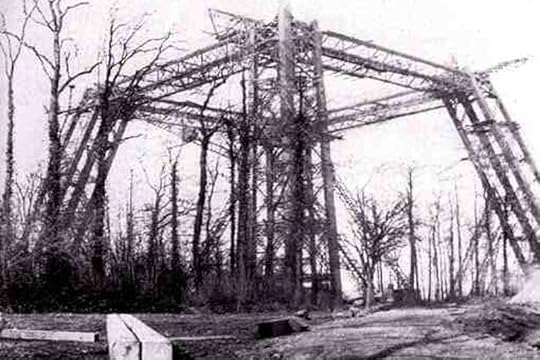

London’s Eiffel Tower

The twin towers of Wembley Stadium were an iconic symbol of English football until they were demolished in 2003 but Wembley Park would have boasted an even more impressive structure had the ambitions of railway entrepreneur and Liberal Unionist MP, Sir Edward Watkin, come to fruition. Irked by the rapturous acclaim that had greeted the opening of the Eiffel Tower, the world’s tallest structure, at the World Fair in 1889, he declared that “anything the French can do, the English can do bigger!” and laid plans to build an even taller tower.

“In another eighteen months”, Freeman’s Journal trumpeted in 1892, “London will rejoice in a New Tower of Babel, piercing the skies some 150 feet higher than the renowned Eiffel Tower of Paris. Not only will the Watkin Tower look down 150 feet on the Eiffel Tower, but it will be capable of taking up three times as many passengers at a time”.

Rather than ape the French and place it in the centre of the metropolis, Watkins chose a 280-acre plot of land that he had bought in the Wembley area, the pièce de resistance of a grandiose plan to build a new community connected to London by the Metropolitan Railway of which he just happened to be the chairman. As Sir John Betjeman observed, when telling the story of the suburbs that grew along the Metropolitan line in a 1973 TV documentary, Metro-Land, “beyond Neasden there was an unimportant hamlet where for years the Metropolitan didn’t stop. Wembley. Slushy fields and grass farms. Then out of the mist arose Sir Edward Watkin’s dream: an Eiffel Tower for London”.

The obvious designer, Gustave Eiffel, refused the commission, remarking that if he did his countrymen “would not think me so good a Frenchman as I hope I am”. Undaunted, Watkin then launched a competition in 1890 to solicit designs for the tower, which had to be at least 1,200 feet tall, topping the Eiffel Tower by some two hundred feet. A prize of five hundred guineas was offered to the winning design.

Sixty-eight designs were received from as far afield as Australia and the United States, showing a bewildering range of imagination, ingenuity, and often impracticality. Designs included a tower 2,000-feet tall looking like a multi-layered wedding cake with a working railway spiralling up it while another, described as an “aerial colony”, came with hanging vegetable gardens and a one-twelfth scale replica of the Great Pyramid on its summit. Some drew their inspiration from other notable landmarks including the spire of Bow Church in Cheapside and, appropriately as it would turn out, the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

The winning design, number 37, was submitted by Stewart, McLaren, and Dunn and, in truth, looked remarkably like the Eiffel Tower, only taller at 1,150 feet, with four levels instead of three, and made of steel rather than iron. Inside there were two observation decks containing restaurants, theatres, dancing rooms, exhibition halls, Turkish baths, and a ninety-room hotel. The top of the tower was reached by a series of lifts where there were viewing platforms, a fresh-air sanatorium, and an astronomical observatory “because freedom from mists at that altitude would mean that the stars could be clearly photographed”.