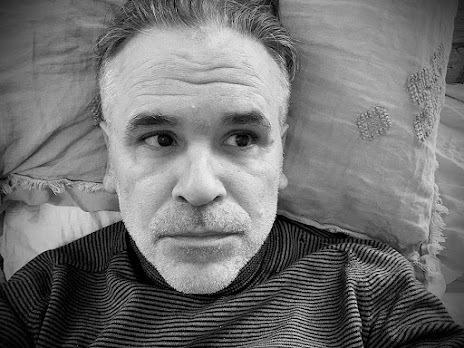

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sean Dixon

Sean Dixon grew up in afamily of 12, including his 8 siblings, parents and a grandmother, throughseveral Ontario towns, predisposing him to tell stories about groups of peoplethrown together in common cause. His debut novel, The Girls Who SawEverything, was named one of Quill & Quire’s best of theyear. His previous books include The Many Revenges of Kip Flynn, TheFeathered Cloak, and the plays Orphan Song and the Governor General’s Awardnominated A God In Need of Help. A recent children’s picturebook, The Family Tree, was inspired by his experience of creating afamily through adoption with his wife, the documentarian Kat Cizek.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

I had a big bereavement whenI was a child. I lost my 15-year-old brother when I was ten to a swift,horrible factory accident. It was a defining moment for me and it governed mylife choices well into adulthood. Some months after I published The Girls WhoSaw Everything — I don’t know how else to describe this — I felt all that griefleave my body. I knew the Epic of Gilgamesh held this kind of power all on itsown, and I do believe that’s why I became obsessed with it, but I didn't knowthat my embodying and retelling of it would have such a life-altering effect onme.

It wasn’t an entirelypositive feeling either: I didn't know who I was anymore. I had always lovedthe unchanging, wise, sad child that had grown up inside of me. I had alwaysfelt I had known death and was not afraid of it. Now suddenly, unexpectedly, Iwas like every other life-loving fool. I was no longer Max von Sydow in TheSeventh Seal, but rather just the strolling player with his family and hiswagon. Faced with grieving people I was just as tongue tied, bewildered andstammery as any normal, well-adjusted person. And, worst of all, I was afraidof dying too. Just like everyone else.

It was awful. I used to havea kind of wisdom. Now it’s gone. Though I will add that the up side ofoffloading all that wisdom was I was finally able to contemplate raising achild of my own. What happens when you don’t think you’re about to leave all thetime.

So I guess the answer is myfirst book changed my life because it made me less afraid to be a parent.

My daughter asked me to readmy latest book to her. So I did. Then she asked me to read my last one — TheMany Revenges of Kip Flynn. My impression, reading them back to back, isthat my experience reading thousands of words to my daughter out loud over thelast several years has paid off, it’s made me a better writer than I used tobe. I don’t add unnecessary details anymore. I seem to have a betterunderstanding of what to put in and what to leave out.

2 - How did you come towriting plays first, as opposed to, say, poetry, fiction or non-fiction?

I was trained as an actor atthe National Theatre School. In our second year, my class made a project with aCanadian actor from Denmark’s Odin Teatret named Richard Fowler forwhich we were asked to create short physical scenes using text and props, etc,where the meaning could be entirely personal and did not have to becommunicated to the audience. This was a liberating exercise for us, aparticularly shy bunch of acting students.

Then I observed, with greatfascination, as Richard took our scenes, ordered them, combined some of them,changed a few details, snipped a few bits, and created something resembling anarrative with them. He called it “a process in search of a meaning.” It gaveme insight into how you could generate a practice of creating raw materialwithout necessarily knowing how you were going to use it. Our physical bodiesprovided the raw material, but I realized that material could have beenanything, could have come from anywhere.

When my class graduated, weformed a company, Primus Theatre, and made a collective creation called Dog Daythat we had begun in third year, still working with Richard Fowler. While inschool, I had written some material for Dog Day in a ‘storyteller’ voice that Iwanted to expand beyond the parameters of that creation. While waiting for theDog Day rehearsals to get underway, I wrote a monologue play called FallingBack Home that ended up being a sort of tragedy about a spinner of tales whosuffers from the delusion that every story he dreams up is true, no matter howoutlandish. By the time the Primus company got underway, I was feeling the pullof responsibility to the script of Falling Back Home so much that the newcompany felt like a distraction from my true priorities. So I quit the company.It was an interesting decision: I was leaving behind my best friends, greatdinners, the opportunity to travel to Denmark and Italy and meet hundreds ofpassionate and interesting people because I wanted to have more time to sit inmy room and write.

So that’s how I started, butthe experience gave me the tools to create a larger work of any kind: playswere just my entry point. My father has always been a big novel-reader, so itwas the great desire for me to do that but I was so, so afraid that I neverwould. When I finally started, adapting my oversized stage play The Girls WhoSaw Everything, I spent eight months writing constantly, always fearing that Iwould quit at any moment. But I had the grid of the story-as-a-play to keep megoing.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I get an idea, an image, andI tell myself it’s never going to happen. (Currently I’m not going to write amodern version of Apuleius’s Golden Ass and I’mdefinitely not going to write a stage variation of Achilles sulking in histent, standing in for all the grievances of men.)

I think my first drafts havea real shape. But they’re a mess on the sentence level. I dispute the idea thatyou have to build a work via one perfect sentence at a time — Donna Tarttwriting The Little Friend. I’m more interested — to use an artist analogy — insketching out the proportions of the full figure and then going back andfilling in the details. If you don’t do that, I think it becomes very hard tothrow things away, which is a necessary part of writing a larger work, and itcan be very hard to tell a full story that feels proportionally satisfying tothe reader. You’re reading and you feel you’ve passed the beginning and nowyou’re moving into the middle, and now you’ve hit the peak and now you’vepassed the peak. To use the artist analogy again: you haven’t committed to anose too large and a forehead too small.

But then, once that is done,I think I really need some help from an editor saying now look this sentencehere: it’s a mess. And this one, and this one.

4 - Where does a play orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I’ve always thought of aplay as something I can write to inspire and challenge a group of people —something that would be fun for a little community of people to do. Myimpression is that most playwrights don’t start from this impulse. With anovel, the impulse is more private. I want to explore this world by myself.

With The Girls Who SawEverything, I was initially challenged to write a play for the women of arepertory theatre company in Montreal that was concentrating on the classicsand so there weren’t a lot of parts for them. All the great parts were for themen. So I set out to create a meaty part for every single one of them.

The younger founder of thecompany loved the play but the older one decided not to pursue it. I’m notsure, but my theory is that he misconstrued the heightened aspect of mycharacters for mockery. The play was doomed by that point, too large forCanadian theatres, although it did get a second life as a theatre schoolexercise.

Then, when I rewrote it as anovel, I dove in to what the Gilgamesh epic meant to me, all the personal stuffthat came into my mind while I was working on the play but had no performativeoutlet. The last third of the novel — when the characters find themselvesfollowing the old Nindawayma ferry ship across the world to a scrapyard in thePersian Gulf — is a complete departure from the play, and I suppose it rendersthe play out of date. It provides a much more satisfying ending, at least. Itmade me realize that it can take a long time to find a really good ending for astory.

For my most recent novel, Isuppose I set out to explore what had thwarted my teenage impulse to makevisual art. I wanted to feel again the joy that I had felt when I used to dothat kind of work.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I love them. I think I’mgood at them, but I also think that audiences who go to public readings are sosuper attentive (compared to theatre audiences, say) that they don’t ascribe alot of value to whether the reader is a good performer or not. The entertainmentvalue is just a side benefit. So my talent for it doesn't really stand out, itseems to me, except in the eyes of people who really care for that sort ofthing. I remember once I tried to behave like a regular, mature writer at apublic reading. An old friend admonished me afterwards for trying to behavelike everyone else. Ever since then, I’ve stopped worrying about it.

My favourite public readingexperience, though, remains a children’s reading at the Ottawa festival, in apacked space. A library, I think? I was promoting The Feathered Cloak, I think.I can’t recall who introduced me but they mentioned that I played the banjo. Soall the kids were asking about the banjo. But I had not brought my banjo. Ithought that would let me off the hook, but then, during the question period,someone asked me if I would sing a song without the banjo. I sang an oldScottish a Capella ballad called The Blackbird Song and then got mobbed. It wasunbelievable. I felt like Taylor Swift.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I think I’ve always held onto that idea from my youth of the process in search of a meaning. what thatidea means to me now, is: I sense that, as a very dull person who only findsdepth — gratefully, humbly — when I’m in conversation with a searching,thoughtful, charming, vibrant, observant person that is not me, I have nochoice but to try to conjure such voices out of the world that surrounds mewhen I write. I try to be attentive to serendipities that provide the rawmaterial and can then be sketched lightly into my work, and later hammeredhome. Perhaps that is gobbledeegook. I look for the questions. I don’t thinkthey’re inside me. It has to be a conversation with the world.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I do think the writer has aresponsibility to cultivate alternative points of view. My alt pov has alwaysbeen a celebration of the imagination, so I can see how that is not asimportant as explorations of culture and class.

8 - Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Not difficult. Certainlyessential. But also: celebratory. I loved working with Liz Johnston on TheAbduction of Seven Forgers. I recall a time when I was trying to conveysomething a little otherworldly, wherein my storyteller was catching a magicianin the middle of a mind-boggling sleight of hand. Liz kept writing back thatshe didn't see it, she didn't get it. I think I rewrote that passage four orfive times before I got it right. And I trusted her judgement 100%.

I also like to write aboutgroups of people. My bio addresses that. It can be tricky to keep the reader’scomprehension when you have several names flying around. Liz was instrumentalin helping me clarify and distinguish the introduction and follow-through ofall those voices.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I love the line from TheMisanthrope (I think) that got retooled in a French Moliere biopic to bemore pointed advice to the writer: “Time has nothing to do with the matter.”

And, along with it: do nothurry, do not wait.

How I interpret thesefragments: you might come up with the essence of your work, the rosetta stone,in five minutes — but it’s a burning a nub that will warm your hands through ahundred thousand exploratory words. An image can drop so deep that whole chapterswill pour out in joyful plumbing of it. Other times, you might spend days anddays just trying to catch something that’s just around the corner. Time hasnothing to do with the matter.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (playwriting to fiction)? What do you see as theappeal?

To summarize: I seeplaywriting as more of a social impulse and fiction as more of a privateimpulse. But Daniel Brooks once said that theatre is a young person’s game, andI’m finding this to be more and more the case. I know fewer and fewer peoplewho are making theatre, which means eventually, inevitably, there will be noone left who wants to play with me. So I suspect, if I want to keep writing ina way that feels meaningful, it will have to be from the more private impulse.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Every time I fall in lovewith a routine, I always mourn it when it’s over and it takes awhile before Irealize that I’ve just started a new routine. But I don’t write at all when I’mworried about the basic welfare of my loved ones. And that catatonia cansometimes go on for months, during which time I starting thinking I need tobecome a gardener, or a tree-pruner, or a teacher, or a plumber.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Ovid. The Golden Legend. PuSongling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. A lot of obscureclassics like the first poems in English or the Carmina Burana. A series ofpoetry and photo collections that were published in the 60s and 70s that myeducator father acquired, called Voices, edited by Geoffrey Summerfield,printed on durable paper. One day I will return to Gilgamesh. Zombie. Troy.Superstition. The first Rickie Lee Jones album never gets old. Get Out of My House from The Dreaming. Running Up That Hill. I aspire to write like thoseKate Bush songs, which are rigorous in adhering to their own interior logic.Self-contained. AWOO by the Hidden Cameras. That first album by Joanna Newsom,which I have not heard in awhile because she doesn't stream.

Florence and the Machine.Lhasa. The Waters of March. Halo. Walking in Memphis. Tracy Chapman, HAIM.

13 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

Old pee in the panel-board,sadly. And pine needles.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes. The Abduction ofSeven Forgers was, for me, a joyful exercise in celebrating the influencesof visual art.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Is it okay if I link to this essay I wrote?

16 - What would you like todo that you haven't yet done?

Honestly? I’d like to fronta band as a vocalist. No instrument hanging off me. I want to dress up,ostentatiously, Prince-like, and dance and sing. If I woke up tomorrow in thebody of a 20 year old, that is what I would do, no question.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’m often haunted by thefact that I looked into the architecture program at the university of Waterloowhile I was a first year theatre student there, and realized that my courselist from Grade 13 read like I had planned to enrol. But I was dissuaded by theseven year long program. Well and a theatre colleague of mine had suffered anervous breakdown while attending that program. That scared me away too. It’sone of the reasons I set out to explore what it means to have a visualimagination as a writer with The Abduction of Seven Forgers.

When I was a kid I lovedFarley Mowat and wanted to be a marine biologist. I’m recalling that becauseI’m currently reading some of his books to my daughter. I was dissuaded frommarine biology when I heard you spend most of the time in a laboratory, not inthe field. But I’ve come to realize that this is true about everything. As awriter, I spend most of my time in the laboratory too.

But if I were just coming ofage right now, though, I suspect I’d want to go fight forest fires. Maybe I’d convincemy backup band to fight forest fires with me, while we’re not doing gigs.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

Being a middle child in avery loud and opinionated family that drowned me out. The thought that‘brainstorming’ inevitably meant going with someone else’s idea. The fact thatmy father has always been a voracious reader and always had a book at hand. Thefact the my elder brother—five years senior to me, who was my mentor in allthings—died when I was ten. I was trying to write a story that morning, beforeI learned that he had died. An SF story called ‘The Circle’ about atime-traveller who loops back to — well, I don’t even know because I neverfinished it.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I loved Malicroix, byHenri Bosco. I loved The Corner That Held Them and Lolly Willowesby Sylvia Townsend Warner. I loved Tarka the Otter. I’d like to find anotheranimal novel that consumes me as much as that one did.

I want to read that Canadianbook about the forest fire fires. Western writer, yes?

I’m trying to read PipAdams’ The New Animals. I am bridling against its rigorous realismdespite admiring it greatly. What is wrong with me?

I read two blockbustersrecently: Cloud Cuckoo Land and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow.I admired them but did not love them.

I loved the film about thehawk-healers in India — All That Breathes. I am a sucker for the Guardiansof the Galaxy movies — all of them, except maybe the one about thestarlord’s dad.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I recently asked a localToronto theatre to reconsider a three-hander from a few years ago that theyrejected. The leadership there has changed so I thought I’d give it anothershot. They have offered a reading in early Feb. But I’ve had a look at the scriptand it truly is a mess. So I’m currently trying to use the limitation of thetheme and the actors I requested to write something wholly new.

(As of today I’m failing,though, because a 4th character has suddenlyrevealed herself, foiling all my plans.)