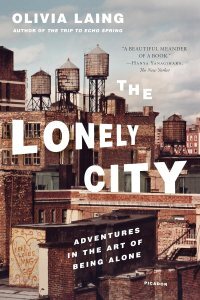

On the Bookshelf: The Lonely City by Olivia Laing

During one of my lonelier periods as a young man I used to spend a lot of time wandering the city where I lived. Loneliness drives us to be around others or maybe to escape ourselves. Such moments tend to amplify the condition, though, as there’s nothing like feeling isolated in a crowd of strangers to really highlight your loneliness.

I’m tempted to say my wandering was aimless, but it wasn’t. It was undirected perhaps, but intentional. I wanted to experience some connection to others or perhaps even to the city itself. So it was I found myself in settings that inevitably attract the lonely — cemeteries, churches, hiking clubs, cafes, writing groups and the like. Who knows how many people like me were also in those places, searching for some connection? Entire communities, perhaps.

It’s this sense of communities of the lonely that pervades Olivia Laing’s book The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone. Equal parts autobiography, biography, art history, art theory and philosophical musing, the book chronicles Laing’s physical and emotional journeys after a breakup and connects them with biographies of famous and little known artists who all searched for or depicted dis/connection themselves in some form or another — Andy Warhol, Edward Hopper, Billie Holiday, Jean-Michel Basquiat and more. We learn about Warhol’s obsession with chronicling everything in his life to surround himself with an ever-present if virtual community, we consider the barriers to connection in Hopper’s famous painting of a cafe at night — the canvas and then windows separating the viewer from the subjects of the painting, who are themselves mostly isolated from one another, in a city cafe that seems to have no entrance or exit — and we experience Laing’s longings that will be so familiar to so many of us.

It’s a meandering yet purposeful book that somewhat alleviates the emotional crisis of loneliness by drawing the reader into Laing’s life and connecting author and reader both to a broader community of yearning souls. The entire book becomes an act of communion of sorts, where we can transcend our isolation by understanding the isolation of others who, despite their fame, were often more alone than we can ever imagine and who were able to convert their disconnection into a form of transcendence through their art. After all, what is a painting or a book or a song or even this review if not an attempt to communicate with others, to connect with others?

“Loneliness might be taking you towards an otherwise unreachable experience of reality,” Laing writes at one point. Isn’t that what all our wandering is about in the end?