All Saints: The Courage to Make Others Suffer for Our Convictions

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the work, consider joining the posse of paid subscribers!

All Saints

When I was a Master’s student at Princeton, I had a number of side hustles to fund my bed and board. In addition to serving as a teaching assistant for the homiletics professor and working as the assistant director for the after-school program at Princeton Junior School, I also fell into a lucky gig as a waiter at the weekly faculty lunch.

Not only did it pay better by the hour than my other gigs, it quite profoundly changed my life and forever altered the shape of my ministry.

I remember at one of those lunches early in the fall semester— around the time when I was considering dropping out of seminary due to how out of place I felt— Professor Max Stackhouse held forth over gray beef tips and over-sauteed squash about some “reckless” and “profane” theologian at Duke named Stanley Hauerwas.

If I’d been honest in narrating my call story to the ecclesial bureaucrats during the ordination process, I would’ve told them this meal was nearly as consequential to me as the Last Supper. To the bemusement of some and the alarmed agreement of others, Professor Stackhouse worked himself up into a red-faced lather about this “sectarian tribalist” named Stanley something or other.

This was not long after September 11, 2001, and Dr. Stackhouse was irate that this Stanley person had the gall to insist that it was now incumbent upon Christians in America to separate the American “We” from the Christian “We.” “Christians in America,” this Stanley person had apparently asserted, “now needed to live in manner that bore witness to fact that the date that changed the world was not 9/11 but Good Friday, 33 AD.”

By the time I served his dessert, the vein in Dr. Stackhouse’s forehead was throbbing. I leaned over his shoulder to fetch his dirty plate just as he griped, “Hauerwas’ arguments are even more irresponsible and inappropriate than the four-letter words and off-color humor with which he makes them.”

Even though I’d gone to UVA for my undergraduate work and had been taught by many of Stanley Hauerwas’ students, classmates, and colleagues, I’d enrolled at Princeton unaware of anyone named Stanley Hauerwas.

But the Law, St. Paul warns, only increases the trespass, and I’d just heard Stanley Hauerwas condemned as being both radical and vulgar. So naturally, I quickly concluded that anyone who could arouse such animus and consternation at a normally tight-sphinctered faculty lunch was certainly someone worth my reading.

As soon as I washed the dishes, I headed over to the Princeton library and checked out a book called A Community of Character along with a set of audio cassettes, lectures delivered by this Stanley person entitled Discipleship as Craft. And because modesty has never been a virtue I possess, I had the gumption to look up the email address of this Stanley Hauerwas person and let him know I had begun apprenticing myself under his work.

To my surprise, at the crack of dawn the next morning, he wrote back to me:

“Dear Jason, I’m so pleased you’ve happened upon my work, even if inadvertently. There may be hope for Princeton yet! Please tell Max he encouraged you to dive deeply into my work, and then write back to tell me how he reacted. While I’m pleased to have you as an apprentice, be warned, Jason. I tell my students at the beginning of every course that I have no intention to teach them in a manner invites them to think for themselves. Rather, my goal is to make my students think just like me. That is, you don’t have a mind worth making up until your mind has been shaped by me. Indeed, to so teach shocks our modern democratic sensibilities; however, to teach in any other fashion is a cowardice the Church mustn’t permit if we believe it’s true that Jesus Christ is Lord.

Your (New) Friend,

Stan”

“Be imitators of me!” the Apostle Paul has the temerity to exhort the church at Philippi, “Become as I am!” Talk about the gall, passing out to the congregation his very own WWPD bracelets “What Would Paul Do?” Paul says nothing less offensive than, “To imitate me is to imitate Christ Jesus our Lord.” I mean, really now— most of us are hesitant to pray in front of other people.

The early Church was no less demanding in their expectations than Paul. According to the historian Alan Kreider in his book, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church, in the first few centuries of the faith the worship service was not the entry point for newcomers into the Church. Corporate worship was instead the final threshold.

Worship was closed to outsiders until after they’d first undergone rigorous catechesis and baptism. Indeed, the first Christians didn’t even do what would be called “evangelism.” In addition, the early Church made baptism extraordinarily strict and selective, rejecting as many catechumens as they accepted. You see, the Church wanted to insure that anyone who bore the name of Jesus Christ would bear faithful witness to Christ.

The first Christians made faithfulness rather than friendliness their priority, and the ancient Church grew, Alan Kreider shows, by being a community capable of saying to the world, “Imitate us! To like we are is to become Christ!”

Recall as well that the early church did not have what we now have, the New Testament. The saints were their scripture.We simply cannot avoid that Paul could and should call attention to himself, because in doing so he believed he was calling attention to Christ.

The Holy Spirit never alights on anything, but bodies.

Accordingly, Paul would have us realize that we must finally reflect Christ’s life to one another if we are to know Christ at all. Ours never stops being an incarnational faith. Jesus is not a principle or an idea. Jesus is not an eternal possibility always available to all persons if they but make use of their experience. Jesus is only available to people bodily— through people whose lives have been touched by Christ and his Holy Spirit and so gospel another person.

As much as we might prefer the lie that faith is intelligible apart from imitation, the liturgical calendar this week reminds us that the Church is necessarily a performative community.That God has raised the crucified Jesus from the dead and made him Lord is a truth claim that cannot be proven through apologetics. It can only be known through exemplification. Embodiment.

The Gospel is a story that cannot simply be told. It must be enacted.No scientific investigation can prove that Jesus is Lord. No philosophical theory can corroborate his resurrection. No social science research can teach someone how to love their neighbor. To know what it means to confess Jesus as Lord requires that someone live a life under Jesus’ Lordship, which also means you are not the arbiter of whether or not you are living a life in line with the Lordship of Christ.

It doesn’t matter when you invited him into your heart; you are not arbiter of whether or not you are living a life in line with his Lordship. As Jesus warned, “Not everyone who says to me, 'Lord, Lord,' will. enter into the Kingdom of Heaven…” You are not the arbiter. The lives of the saints are the arbiter. The saints are those who embody how to live with the intentions that the story of Jesus demands of the whole Church.

Demands.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we resist Paul’s emphasis on imitation not because it strikes us an example of Paul’s alleged hubris, but because it strikes against our own lack of nerve.

A couple of summers ago, when our intern, David King, preached his first few sermons, a number of you commented on your way out the door, “David preaches just like you!” To my surprise, my immediate reaction to such comments was to rebut them, to dismiss the likeness and to reaffirm the importance for preachers to find their own way and discover their own voice in the pulpit.

I’ve known David since he was six years old, so it’s not unusual that he would preach like me.

Still, I did my best to shake my head at any who understood David as imitating me. If that were the case, then suddenly I have a responsibility to David— and possibly others— that I didn’t choose.

Not to mention, to discover that someone else might be imitating you, your example, is suddenly to wonder if you’re prepared to be exposed to the discerning glare of an apprentice.

What if they find that you’re doing it all wrong, or learn that you are not who you pretend to be?

And what if, I thought, David’s imitation of me led him into ministry? Being a preacher is a little like being nibbled to death by ducks, what if he followed me into an endeavor that eventually did him harm or gave him not the joy he had expected? What if one day he holds me liable for his disappointment, or his frustration, or his meager pension?

Stanley was right all those years ago.What we couch as modesty and respect is cowardice.“There are many paths to God— we’re all on a journey to the same destination.” “Who am I to say what’s right?” “Faith is a private matter, I want you to make up your mind for yourself.” “ I’m letting my kids choose their religion for themselves.”

We’re reluctant to take our convictions so seriously that others might take them seriously because, of course, we are not prepared to make others suffer for of our convictions. It’s this lack of nerve that produces a nonsensical statement such as, “I believe Jesus Christ is Lord, but that’s just my personal opinion.”

Nico Smith was a South African Afrikaner minister, a prominent opponent of apartheid, and a professor of theology at the University of Stellenbosch.

Eventually in the mid-1960’s, Nico Smith began aggressively challenging apartheid in his classes, which provoked his superiors who wanted him to give his students the theological material without shaping them in a particular direction. “Teach theory, not conclusions,” they ordered.

Smith didn’t heed them. He also joined public protests against the government's bulldozing of squatter shacks in Cape Town.

Summoned before a church commission to justify himself, Smith decided to resign his professorship. Instead, he left the pro-apartheid Dutch Reformed Church and joined its colored branch. In 1982 he undermined the apartheid regime by preaching in an area of Pretoria designated for non-whites only. And in 1985, he and wife moved to that community to live.

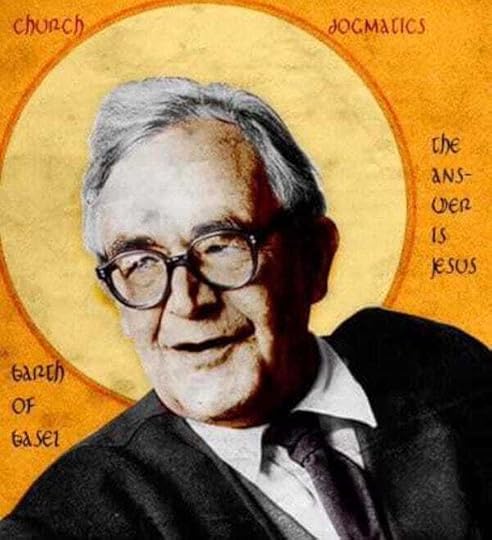

Nico Smith attributed his peculiar and dangerous witness to an encounter he had with the theologian Karl Barth in the early 1960’s.

A staunch supporter of apartheid at the time, Smith attended a lecture by Barth and the two spoke afterward. Smith describes the key moment of the exchange as follows:

“Barth then looked at me and said: “May I ask you a personal question before you leave? Are you free to preach the Gospel in South Africa?” “Of course,” I replied, “I’m completely free as we have freedom of religion in our country.”

Barth immediately responded by saying that that was not the type of freedom he had in mind.

He wanted to know whether I, if I came across things in the Bible that were not in accordance with what my friends and family believed, would be free to preach about such things? Or would I temper the demands of obedience?

I was once again embarrassed and said I really did not know as I had never yet had such an experience.

Barth then leaned a little forward in his chair, and said, “But you, it may become even more difficult. You may discover things in the Bible that are contrary to what your country is doing. Will you be free to preach about such issues?”

Once again, I had to say, “I really did not know.”

Barth then just said, “It’s OK, you may go.”

In the tram back to the city center, I thought about Barth’s questioning of me, and I said to myself, “I’m sure Barth thinks we in South Africa are Nazis and he wanted to warn me against apartheid. Barth had had the courage of his convictions, the courage to make me suffer, potentially, for his convictions. With his gentle questioning and in so many words, he had said, “Imitate me!”

The world is quite right to judge Christianity by the lives it produces. Judging from the polls, this is going to be a long-term problem for the church (in America).

There is no gaslighting our way out of the truth that Christian discipleship is utterly dependent on our ability to identify examples.While it’s true that the Bible says we are all saints right now, that Jesus is our righteousness, that he is both our justification and our sanctification, it’s also true that the reality of who we are in Jesus Christ is exemplified by some better than others.

That’s the embarrassing, unspoken truth when we light these candles for the dead every All Saints Day.

The Church is not a democracy.There are some who bear a better witness than others.But this is good news! This is good news because the nature of discipleship didn’t change after the Cross. It’s always been a Master-Apprentice relationship. Discipleship is not about knowing or doing certain things you would not know or do if you did not know Christ. Discipleship is about being transformed, and transformation is not the result of facts, but the result of teaching. It’s the product of formation, not information.

Our fellowship as Christians, therefore, is a moral practice. We are not friends in Christ as an end unto itself. Most of you might not choose me as your friend. But, we are friends brought together by the Living God for the common activity of trying to give a visible witness to the Lordship of Jesus.

And this is no easy or uncontested task.

That our citizenship is in heaven means that the salvation brought in Jesus Christ has made us citizens of a time and space that is in tension with all other forms of citizenship. It’s exactly through the process of conforming ourselves to the Cross, it’s through the process of conforming ourselves to the Lordship of Christ, it’s through the process of suffering the consequences of living as though God really has raised Jesus from the dead— it’s through that process of enactment and embodiment and exemplification of our ultimate citizenship that the Living God transforms us into the Body of his glory.

The pursuit of happiness is not necessarily the pursuit of the good. We need to be shown the good. We need witnesses. Thus, our hope for the world rests not in what you do with your ballot on Tuesday. Our hope for the world rests in what we remember this week: That the Living God is capable of raising up a peculiar people, citizens of heaven, who embody how to live with the intentions that the story of Jesus demands.

When I first became a pastor, I was extraordinarily uncomfortable and embarrassed whenever a little child would come forward for the children’s sermon and, seeing my robe and beard, confuse me with Jesus. Today I believe the possibility of such a likeness is not only a part of God’s good humor, I believe it is the way in which God has elected “to make all things subject to himself.”

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers