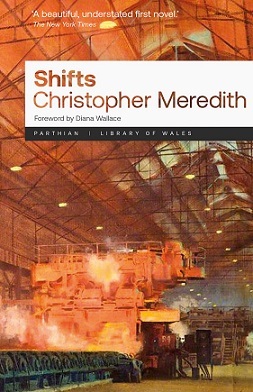

Review of Shifts by Christopher Meredith, this edition pub. Parthian 2023

It was impossible to go back to what they had been, the river only running one way.

This is a new edition of Christopher Meredith’s debut novel, first published in 1988 but set a decade earlier at the end of the steel industry in Wales. It centres on a group of men employed at a steelworks faced with imminent shutdown, their work not only arduous and dangerous but, now, intrinsically useless:

“The drums had been shoved one after the other under the leaking grease pipes until the maintainers eventually came round to repair them. Lew Hamer had shown Jack and Kelv the job, telling them to manhandle the drums out and chuck them on a spoilheap. They had sat and looked at the drums for a while. Jack dimly recalled myths about Greeks being set pointless and impossible tasks.”

Jack is a returner, come back to the place of his childhood having failed to make a go of things elsewhere; he is about to learn the truth of Cavafy’s remark that messing your life up in one place generally means you will do the same anywhere. His friend Keith, more rooted, is trying to make sense of his life and work in the valley by studying the local history that led to the steelworks in the first place, though hampered by the fact that he has no Welsh and cannot read the gravestones and documents that hold the information he needs: “The notes Keith held were in a language that was his own, but that he could not understand.” Robert, an obsessive, asocial bachelor, is “Robert” at home but “O”, a nothing, at the steelworks.

In many ways this is true of all the men who work there, whose individuality is not needed when on shift. But though they may not enjoy the job, it defines them, and its loss threatens to leave them not only insolvent but no longer knowing who they are and what their place in the world is. The women of the valley have more chance of work, but are no better off for job satisfaction:

“She was a widow, and worked in a factory from eight to half past four. The factory made electrical components, she told him, but she didn’t know what they were for.

She explained to him once that if she fitted together twice as many of the little pieces as she was meant to fit together for her basic rate she got a bonus of thirteen pence per hour. It only made you tired, she said, if you thought about it.”

Three things come through the writing very clearly. The first is the contrast between the natural and built environment these characters live in, a contrast that tends to surprise those seeing the valleys for the first time. The house where Keith and his wife Judith live has a “cracking view” across the valley, but like Gus Elen, you are better off ignoring the characterless ‘ouses in between, not to mention the factories and spoil heaps. The second is the sense of imminent danger just below the surface in the steel mill, where there seem to be umpteen ways to do oneself a mortal injury:

“Without looking down, Willy sidestepped a pool of slime in which a mangled steel cranesling lay contorted like a writhing snake. Suddenly he stopped, turned, and raised a warning finger. ‘Mind’ he said inexplicably. ‘Look here.’ He pointed into the gloom. ‘Know what these are?’ Jack strained his eyes and saw a bank of filthmantled metal boxes fixed along the wall. ‘Fuseboxes’ he said wondering if it was a trick question. ‘Thassright’ Willy said. His face relaxed for a moment but then the earnestness returned. ‘So be careful where you do piss. It ’ouldn’ be a nice way to go.’”

The novel is set at a the time of a seismic “shift” in the South Wales economy, and the third thing that comes across is how ill prepared people are for it and how little they can do about it. Some, on the mill’s closure, opt for similar jobs elsewhere in the country, which, given that the whole industry is doomed, merely postpones their problem. Some move on with no very clear idea of where and to what they are going. Some stay where they are and try for other jobs in the area, though it is women who have the best chance of factory assembly-line work. Meanwhile Keith’s observation about history – “it’s not something you can escape from” is borne out when a film crew arrives at the moribund factory and the men find they have themselves become historical exhibits:

“All the men were issued with hard hats, and some ingots were filmed as they were rolled into slabs. Jack laughed at the nervousness of the crew and the way they jumped when an ingot boomed and cracked out sparks as it hit the rolls. Wayne asked one of them what it was for. He was vague about the answer he got, but it was something about archives. Jack stood next to an old rigger wearing huge leather gloves and a metal helmet and they both tried to edge into the shot. But the rigger was watching the mill. He told Jack they were watching history and Jack, trying to look solemn, said nothing.”

The energy in the novel comes from its unusual setting, and the author’s assured familiarity with it – he had himself worked there. But the assurance of the prose, in a first novel that never sounded like one, was down to pure talent. Jack’s sudden sense of transience at one point is a typically sharply-conveyed moment:

“It struck him that everything sat lightly on the hillside. The cars, the pine trees on their shallow plates of roots. Looking at the stepped roofs of the houses, he could imagine them slipping and fanning down the hill like a tipped shelf of books.”

As Diana Wallace reminds us in the foreword, Shifts, from when it first came out, has been “the classic novel of de-industrialisation in Wales” and it is good to see this new edition from Parthian.