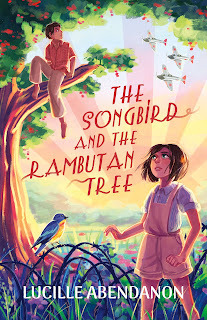

Interview with Lucille Abendanon, Author of The Songbird and the Rambutan Tree

Thanks so much for visiting Smack Dab, Lucille.You have such an incredibly important story to tell. Please tell us a bit aboutThe Songbird and the Rambutan Tree:

Thank youfor having me! The Songbird and the Rambutan Tree is a middle grade historicalfiction novel about a girl called Emmy who lives in Batavia, in the Dutch EastIndies (modern day Indonesia) with her Papa. Emmy’s gift is her singing voice,but when tragedy strikes, she loses her ability to sing. With World War Twolooming, Emmy’s papa wants to send her away to safety, to the one place shedoesn’t want to go: singing school in England. So Emmy does everything she canto stay in Batavia, roping in her best friend Bakti and putting them both indanger. Her plan works and she sabotages her only chance to escape, ruining herfriendship with Bakti in the process. The Japanese army invades, and Emmy isseparated from her Papa and taken to a prisoner of war camp called Tjideng.Worst of all, the meanest girl in school, Violet, is put in the same house asEmmy. Emmy must face the pain of losing the ones she loves, find the will tostay alive in Tjideng, and somehow find her voice again.

Wheredid the idea for this story come from?

The book is inspired by my Dutch grandmother’s experience as a prisonerof war in Tjideng during WW2. Oma Emmy spoke openly about her years in Tjideng,and I was captivated by her stories. Our conversations spanned twenty-fiveyears.

Wasit difficult to write the story, one that was so close to your family?

Initially, yes. I always knew I would write Oma Emmy’s story one day,but I wasn’t sure what form it would take. It didn’t feel quite right to writeit as an adult novel. I think it felt disrespectful to my grandmother in someway. She was an adult when she was imprisoned in Tjideng, and to bring her tolife on the page, I would have had to colour in certain aspects of her life andemotions, and I just didn’t feel that would be respectful. She always used tosay, “You can listen to my words, but you’ll never truly know how it felt to bethere.” And she was right. I couldn’t presume to put myself in her shoes.Writing it as a middle grade novel took that one step back and put a little bitmore distance between my Oma Emmy and the protagonist Emmy. Emmy in the book is100% inspired by the real Emmy: her grit, her determination, her fightingspirit, her sense of humor, her artistic talent. But it’s not a true to lifeexact depiction of my Oma, if that makes sense.

Didyour Oma give many details about the actual prisoner of war camp? Did you findyourself inserting details to keep the story moving?

Oma Emmy gave me every single detail of the war camp, and it’s all inthe book. Well, the things appropriate for a middle grade audience, anyway. Hermemories of those years were crystal clear, like it happened yesterday. I thinkthere are elements of her story that seem so fantastical to us all these yearslater, like eating weevilly rice, sleeping in a cupboard, or bowing for hoursin the hot sun, that I really didn’t have to embellish or add anything to keepthe story moving. From a plot point of view, I made sure it was exciting, butthe facts of life in Tjideng are exactly as Oma described them to me.

Howdid you balance fact and fiction?

I was very fortunate that through my Oma’s stories, I had a detailedfactual framework through which I could weave the fictional story. I had a listof elements from Oma’s stories I wanted to include, for example, building thebomb shelter in the garden; the army truck that transported them to Tjideng;the daily bowing at tenko; House Two and sleeping in a cupboard; LadyMountbatten and the toilet paper; working in the central kitchen, all of theseelements, and so many more are all part of Oma’s lived experience in Tjideng.Bringing the characters to life within the historical context was thrilling,and they took on a life of their own. Kitty, for example, arrived one dayunannounced and wrote herself into the story! Yet, she is rooted in factbecause there were many British women in prison camps all across the region.

I also wanted to portray the Indonesian struggle for independence thatwas going on at the same time, and the impact it had on Emmy and Bakti’sfriendship. That was definitely an area where I wanted to stay true to history,whilst also trying to imagine how two children on opposite sides would beaffected.

I was very conscious of always remaining true to the history on bothsides, especially since the events in the book are still within living memoryfor some. I did a lot of research, spent time in Indonesia and visited Tjideng,and only when I felt sure I grasped the historical context, could I drop myfictional characters in and let them get on with it.

Whatstruck me from the very beginning were all the sensory details. You immediatelyknow you’re someplace quite different than the US. Did your travels help informthe worldbuilding?

That’s really lovely, thank you. It was really important to me to bringthe setting to life. I grew up partly in the English countryside, and partly inSouth Africa and I’ve always felt very close to nature. Whenever I move to anew country, nature is always a grounding force for me, and so it felt naturalfor Emmy to be the same. I lived in Southeast Asia for five years, and itdefinitely informed the worldbuilding for this novel. For example, the Asian Koelbird, which wakes Emmy up just before dawn, comes from when I lived in Bangkok.There was a huge tree outside my bedroom window, and in the spring the Koelwould wake me up every morning with its loud call. It was magical. Childrenexperience the world with all of their senses, much more than adults, so Iwanted the wonderful sensory details of Indonesia to be integral to the story.

Whatwas it like to visit the actual house where your Oma lived?

Very emotional, especially when I phoned her from outside House Two. Ifelt incredibly grateful that she (and my Opa) survived the war, because ifthey hadn’t, I wouldn’t have been born. I felt immensely in awe of her formaking it through those years, and going on to live the wonderful life she did.It also felt like I was touching the past, like 1942 was right there, justbeyond my fingertips. Just for a moment, time evaporated.

I have to admit, this stirred all sorts offeelings as I read–I had a great, great grandfather who was a prisoner inAndersonville, and have tried to track down a radio interview he supposedlygave to no avail. I can only imagine the emotions your Oma’s story must havestirred in you as you listened. (It can be hard to listen to, but it’s soimportant to get these stories down! Otherwise, they’re lost forever.) Whatadvice would you give anyone getting started in documenting family history?

Oh wow, itwould be amazing to find that radio interview!

I think newgenerations often discount older generations as being uncool, or evenworse…irrelevant. Whenever I go on about living without smart phones, or how weonly had an hour of kids TV in the afternoons, my kids roll their eyes! But Iam always telling them there is value in the past, and magic in listening tothe people who lived it share their memories of a world long gone.

My adviceto anyone interested in documenting family history is:

1. If you have a family member you can talk to, ask lots of questions. Not just ‘what happened’ questions, but ‘how did you feel’questions too. The magic of history is often in the small details or feelingsthat aren’t immediately obvious on the surface, so dig a little, ask open-endedquestions.

2. Treat thepast like a foreign country and your family member as your tour guide. Ask themabout what they ate, what clothes they wore, what they did after school, whatwas on the news at the time, what music they listened to. Notice thedifferences between their world back then, and our world now, but notice thesimilarities too.

3. Become adetective. Human memory isn’t perfect, and sometimes, you might have to fill insome of the blanks. If you’re researching someone in your family who lived along time ago, be creative with your Google searches and try to think ofdifferent ways to phrase things. Don’t stop at Page 1 of Google, go down therabbit hole and see what results there are on page 24! I have found a lot ofinformation by researching my family tree, rather than a single person. Jotdown leads as you discover them, no matter how trivial, and start joining thedots. There are also organisations like Ancestry.com, where you can subscribeto gain access to census registers or search WW2 service records. Look at birthand death registers. You can even find ship manifests online, if you know yourancestor travelled somewhere by ship, for example. Often, if you dig deep andwidely enough, you’ll discover something you weren’t expecting that giveswonderful context to the person you’re researching. I was researching a soldierwho died in 1890, and came across his will in an database of British soldierswho died abroad. In it, he left his collection of books to his sister. Thattiny fact says so much about him and their relationship!

What’snext?

I’m currently workingon book two. Set at the very end of the First World War, it’s a story of a girlcalled Percy who comes back to England from South Africa, to be reunited withher father who has been wounded fighting in France. But she soon learns he ismore gravely ill than she was told. She begins to suspect the doctor lookingafter him is doing more harm than good, and when her father starts calling outa strange name in his feverish sleep, Percy sets off on a race-against-timejourney to uncover a family secret. There is also a talking African pied crowand a magnificent dappled grey horse called Valerian.

Wherecan we find you?

I am @Author_Luc ontwitter/X; @lucilleabendanon_author on Instagram. And my website is www.lucilleabendanon.com where you’ll find lots of behind thescenes information about the book and the real Emmy.