An 18th Century View of Robin Hood

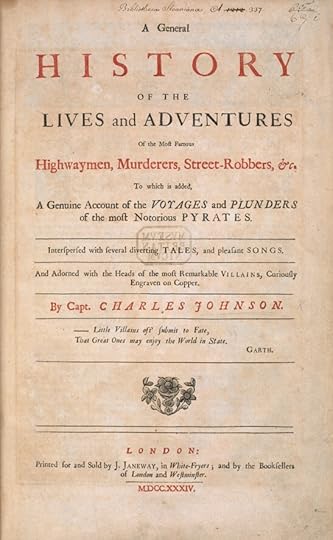

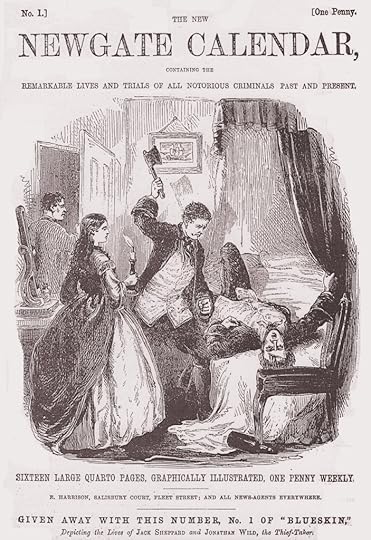

While researching my ‘Molucca Star’ quartet of novels concerning pirates and smugglers of the 18th century, I naturally read a lot of contemporary accounts of criminals found in the Newgate Calendar as well as Captain Charles Johnson’s influential 1724 book A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates. It was in Johnson’s followup book A General History of the Lives and Adventures of the Most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers & Street-Robbers that I found an interesting connection to a couple of my other novels, the ones about Robin Hood.

Charles Johnson shamelessly plundered an earlier book on highwaymen by Alexander Smith, published in 1714, mixing Smith’s accounts of various villains with his own accounts of famous pirates. One account he lifted from Smith’s book was a summary of the life of England’s famous outlaw, Robin Hood. It’s a strange inclusion to place a most likely fictional medieval outlaw among real-life villains and thieves like Moll Cutpurse and Blackbeard the pirate but there was a voracious appetite in the 18th century for accounts of criminals and their gruesome fates exemplified by the phenomenon of the ‘criminal biography’; lurid tales of men and women giving into idleness and embarking upon lives of sin and wickedness before meeting their ends, usually at the end of a rope. And, as Robin Hood is perhaps one of the most famous highwaymen of all time, it probably shouldn’t be too surprising that he also got the criminal biography treatment.

But, when viewing the famous outlaw through 18th century eyes, we see some stark differences to the Robin Hood of medieval ballads or the popular fiction of modern times. Johnson’s book places him in the reign of Henry II (1154 – 1189), earlier than the reign of Richard the Lionheart (1189 – 1199) of most modern books and films, and earlier still than the setting of the medieval ballads which is that of an unspecified King Edward (meaning somewhere between 1272 and 1377). The account also dispenses with the idea that Robin Hood was descended from the earls of Huntingdon (popularized by the Tudor playwright Anthony Munday). Instead, Robin is the offspring of poor shepherds in Nottinghamshire.

As in most criminal biographies of the time, Robin ditches his honest trade and throws in his lot with villains. Johnson then gives a brief selection of adventures similar to what we get in the medieval ballads. such as Robin winning an archery tournament organised by the king and tricking the sheriff by selling meat at ridiculously low prices. Although it is mentioned that Robin robs the rich and gives to the poor, he comes across as a much more cold-blooded thug in Johnson’s account. The ballads have Robin entering in the service of the king upon meeting him. Johnson has him simply rob him.

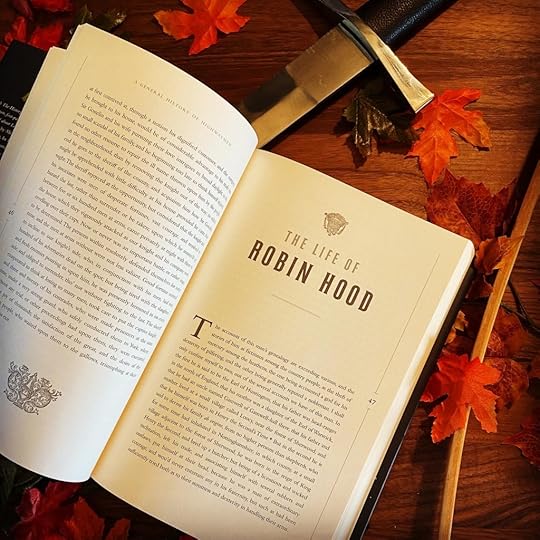

William Stutely and Robin Hood from Captain Charles Johnson’s ‘Most Notorious Highwaymen’

William Stutely and Robin Hood from Captain Charles Johnson’s ‘Most Notorious Highwaymen’In the medieval ballads, Robin grows sick and goes to a priory at Kirklees to be bled by his cousin, the prioress. Through collusion with her lover, Sir Roger of Doncaster, the wicked prioress bleeds Robin to death. Johnson’s account of Robin’s death follows this to some extent with the important difference of him retiring to a monastery ‘struck with some remorse of conscience’. This is in keeping with the criminal biographies of the 18th century which were intended as morality tales to deter readers from following in the footsteps of their sinful subjects. Far from being a hero of the people, Robin feels guilt for his life of wickedness and is eventually punished for his crimes.

While Johnson’s account of the life of Robin Hood gives us nothing we might rely upon as historical evidence for the outlaw’s life (it was written far too late and Johnson was known for embellishing facts to a degree that they might as well be fiction), it is an interesting example of how the legend of Robin Hood changes with the retelling to suit its audiences.

And you can read my own accounts of Robin Hood in both Lords of the Greenwood and Rotherwood: A Prequel to Ivanhoe. Both available in print and for Kindle from Amazon.