Alfred E. Goldman

In March, 2020 the Federal Reserve injected massive amounts of liquidity into the markets in response to a blow-up in Treasury basis trades. I wrote about it here.

In recent weeks, the Fed, the BIS, and the BoE have raised red flags about the renaissance of this trade and the resulting potential for systemic risk a la 2020. Not all are convinced. Goldman Sachs in particular is in Alfred E. Neuman mode: What? Me worry?

FT Alphaville quotes Goldman’s rates strategy team as follows:

We do not think the trade poses a major risk to Treasury markets in the near term . . . Leverage in the system is materially lower than it was in 2019/20 as a result of a series of [initial margin] increases (and price declines). The large increases in IM, which were in theory calibrated to the extremely elevated levels of Treasury market volatility of the past few years, should mean additional large increases may not be necessary — at least in the near term, we expect to migrate to a less volatile rate regime.

This assessment is based on a fundamental error that I went on about ad nauseam in the post-Great Financial Crisis clearing debate, specifically, concluding that if leverage goes down in one part of the system it goes down systemically. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

Yes, the ostensible purpose of higher margins is to reduce leverage in the margined trades. But especially for the hedge funds and other sophisticated entities who engage in the Treasury basis trade at scale, they can substitute one form of leverage for another.

As a first approximation, a fund has a leverage target or a level of debt capacity, it can fund the higher margin in the less leveraged futures trade by increasing leverage elsewhere. The funds will typically evaluate leverage holistically, not on a trade-by-trade basis.

It is therefore fundamentally logically flawed to conclude that “leverage in the system” (which is in fact source of systemic risk) has declined because it has gone down in one piece of it.

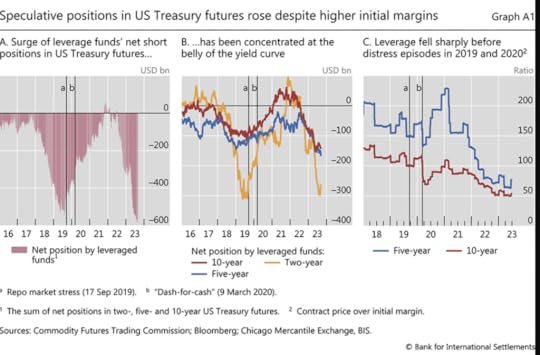

If there are constraints on funds’ ability to offset mandated leverage reductions in one type of trade by increasing leverage elsewhere, that would increase the cost of engaging in that type of trade and would impact the scale of that trade. But what has alarmed the central bankers is exactly that the scale of the trade has increased and now exceeds its 2020 level:

Note that leveraged funds’ Treasury futures shorts are currently substantially larger now than in 2020. Thus, despite higher margins, the scale of the trade is subsantially larger–and it is the scale–and the concentration–of the trade that poses systemic risks.

This bigger scale could be because raising margins doesn’t really constrain the ability of funds to lever up to engage in basis trades. Or it could be that even though the higher margins raise the cost of the trade, the spread has widened sufficiently to offset, or more than offset the higher cost. For example, constraints on dealer balance sheets that impair liquidity in the cash market could depress cash prices relative to futures prices.

Goldman’s errors don’t end there. One thing that could spark a margin spiral is an increase in initial margins that induces mass liquidations that lead to changes in the basis that lead to large variation margin obligations–something that Goldman doesn’t mention.

Alfred E. chimes in again here: “The large increases in IM, which were in theory calibrated to the extremely elevated levels of Treasury market volatility of the past few years, should mean additional large increases may not be necessary — at least in the near term, we expect to migrate to a less volatile rate regime.” That is, Goldman’s conclusion is essentially based on a very benign view on Treasury volatility.

There are myriad reasons to take a different view. The US’s acute fiscal situation and the accompanying periodic debt limit dramas. The constrained balance sheets of dealers that limit their ability to supply liquidity to the Treasury market. The prospect for an extremely chaotic election year. And geopolitics, with now two major disturbances ongoing (Ukraine and Israel/Gaza) with one continually on the boil in the background (China/Taiwan). And highly unsettled geopolitics with a feckless and befuddled administration at the tiller.

That is, it isn’t the level of margins that really matters. It is the possibility that margins may increase due to higher volatility. Goldman/Neuman isn’t worried. I think that’s unduly optimistic. Furthermore, an assessment of systemic risk must be based on the likelihood that Goldman’s don’t-worry-be-happy opinion is wrong.

And remind me: did Goldman predict the increase in Treasury volatility in 2019 or 2020? Stuff happens. Unknowns and unknowns and all that.

Furthermore, higher volatility->higher IM->liquidation of basis positions->margin spiral isn’t the only potential source of systemic risk. Other economic shocks can cause leveraged funds to slash positions and leverage, leading to liquidations of basis positions and the triggering of a margin cascade. That is, there is the possibility of fire sales.

These shocks can be systematic–a broad decline in stock or bond markets–or concentrated at a few funds, or even one, due to bad trades in other markets.

The 30 25 year anniversary last month of the LTCM collapse brings the latter to mind. Bad bets on convergence trades forced LTCM to liquidate and delever. Understandably, it attempted to unload its most liquid positions–including short Treasury futures. Treasuries had a massive rally on LTCM day that was not matched by a similar rally in the underlying, less risky Treasuries.

A squeeze–not unheard of in government debt futures markets–can also impose losses on basis trades, leading to liquidations that can exacerbate the price impact. Or a Treasury flash crash (in yields, and hence a flash spike in prices) like on 15 October 2014.

In sum, size does matter. Basis trades have become big again, and the factors that lead Goldman to parrot Alfred E. Neuman are hardly persuasive. From a systemic risk perspective, basis trades represent dry tinder that can explode into flame. Can does not mean will. But the possibility is there, and the effect if the right spark hits the tinder depends on the size of trade. The big scale and concentration of this trade thereby justify far more concern than Goldman expresses.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers