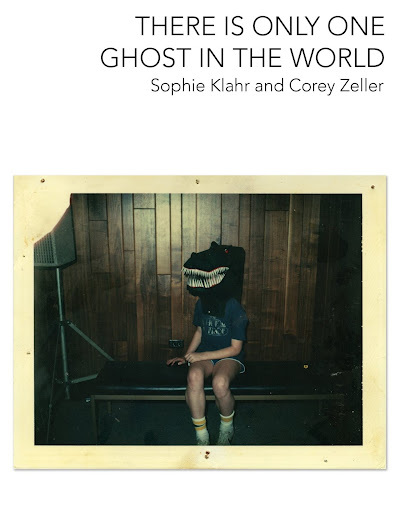

Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller, There Is Only One Ghost in the World

My mother was reading abook to me in bed when we saw the reflection of flames on my bedroom wall. Acrossthe street, the neighbor’s house was burning. I remember being outside in mynightgown, barefoot, my feet in the runoff the firetruck bled, ambulance-menrustling onto the stretcher something dark. My parents told me later that ourneighbor, the old woman I called Aunt Heppy, had died, and that her old whitedog had died too, but that her German shepherd puppy had survived. It jumpedthrough the big glass window of the living room, breaking the broad pane. At school,everything was uniform. The kids all wore the same outfits and their parents allhad the same medications. You looked out the window most of the time. Youlearned more than anyone should ever know about the sky. You drew a line with astick in the new snow and dared a friend on the other side to cross it. Onceyou cross it, you can never come back, you told him. He was reduced totears, and you got in trouble, even though his explanation made no sense toanyone. They told me I could never come back, he wailed. Only when I wasgrown-up did I realize that it couldn’t be true, that the puppy could not havebroken the glass. I asked my mother, and she admitted it wasn’t true.

Selectedas the winner of the 2022 Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Contest is Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller’s collaborative

There Is Only One Ghost in the World

(Tuscaloosa AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2023), an accumulation of untitledself-contained first-person stories, none of which are each longer than asingle page, that appear to connect or thread only loosely through structureand tone. I’m startled by how each narrative of seemingly random turns allowsfor a different kind of structure, one that composes fiction almost akin to thearc of a poem, moving from moment to moment, and allowing the collision andaccumulation of these varying threads to provide connection only through theact of reading, and the reader themselves. There is nothing straightforward here,and there are some stunning and powerful moments throughout these pieces, woveninto the larger fabric of this incredibly interconnected book-length quilt,offering wisdoms, comforts and important truths. “A girl you loved once lovedyou more and got angry when you didn’t love her like that,” the two of themwrite, “like, back enough. She is angry enough to say that you aren’t queerenough. This is always the problem—others drawing little boxes around yourdesire, waiting at a long panel like a spelling bee competition, waiting foryou to fumble.” Another piece offers: “Optimism is a chandelier. It swings toone side catching some light. It swings back and catches the dark. Pessimism,on the other hand, is nothing but a weathervane, a lightning rod.” Orelsewhere: “A piece of what elegy can do is hold an absence by naming it, asif, by saying its endlessness, it is, for a moment fixed in time, when so oftenthere seems no end to grief, only its opening. Even a poem on endlessness hasan ending, a hand, for a moment, resting on one’s shoulder.”

Selectedas the winner of the 2022 Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Contest is Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller’s collaborative

There Is Only One Ghost in the World

(Tuscaloosa AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2023), an accumulation of untitledself-contained first-person stories, none of which are each longer than asingle page, that appear to connect or thread only loosely through structureand tone. I’m startled by how each narrative of seemingly random turns allowsfor a different kind of structure, one that composes fiction almost akin to thearc of a poem, moving from moment to moment, and allowing the collision andaccumulation of these varying threads to provide connection only through theact of reading, and the reader themselves. There is nothing straightforward here,and there are some stunning and powerful moments throughout these pieces, woveninto the larger fabric of this incredibly interconnected book-length quilt,offering wisdoms, comforts and important truths. “A girl you loved once lovedyou more and got angry when you didn’t love her like that,” the two of themwrite, “like, back enough. She is angry enough to say that you aren’t queerenough. This is always the problem—others drawing little boxes around yourdesire, waiting at a long panel like a spelling bee competition, waiting foryou to fumble.” Another piece offers: “Optimism is a chandelier. It swings toone side catching some light. It swings back and catches the dark. Pessimism,on the other hand, is nothing but a weathervane, a lightning rod.” Orelsewhere: “A piece of what elegy can do is hold an absence by naming it, asif, by saying its endlessness, it is, for a moment fixed in time, when so oftenthere seems no end to grief, only its opening. Even a poem on endlessness hasan ending, a hand, for a moment, resting on one’s shoulder.”Thestories touch on, and even return, like a skipping stone bouncing across water,to subjects including queer desire, loneliness, trauma, politics and culturewars, hope and memory, one thought immediately following another, movingthrough moments and references that fade in and out of view with remarkableclarity. As one piece offers: “Being pansexual doesn’t mean that you areattracted to more people than anyone straight or gay might be. It just meansthat desire is a kaleidoscope, and you are all of the pieces inside.” I’mcurious at how the back-and-forth between these two authors worked, exactly, ifeach composed individual pieces that bled together, or if each piece itself hasthe hands of both authors within; in a certain way, none of it matters. There arecertain directions that make me wonder if a handful of pieces were written byone author over the other, but on the whole, the tone is incredibly consistent,providing a wonderfully coherent whole between these two writers, during thepandemic era. As they write as their “Note on Creation” at the end of thecollection: “This book was written collaboratively over the course of eightmonths during the Coronavirus pandemic (November 2020-August 2021), in a singleshared Word document, from six states away.” I’m now curious to see further oftheir individual works: on her part, Los Angeles poet and editor Sophie Klahris the author of the poetry collections Meet Me Here at Dawn (YesYes Books,2016) and Two Open Doors in a Field (Backwaters press, 2023), and CoreyZeller is the author of MAN VS. SKY (YesYes Books, 2013) and YOU AND OTHER PIECES (Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2015), none of which I’ve seen (I’mclearly behind on my reading). Oh, this is a book I wished I’d written; and I amterribly jealous.

Fish have something inthem called a lateral line—this is what helps their schools stay together. Whenthey want to stay still, they face upward. Into the current. The day closesitself like an orphan’s locket, the lip of a candle resembling lace almosttouching the inside of a thigh. Now, and only now, you fail to find adifference. Some handless beauty. Blinking and squinting at the clearestpossible scene. Truth reversed does not make a lie. A lie reversed does notmake truth. The truth of a person is different than the truth of the poem. Youtry to make a Venn diagram of this, but can’t figure out what to put in thethird circle or in the pill shape of the intersection. A certain type of antscollect the skulls of other ants to decorate its nest. There is a type of sharkthat new theories say may have a lifespan of up to six hundred years. InGreenland, one is caught that scientists estimate as being between two hundredand seventy-two years old and five hundred and twelve years old. There arecertain types of crystals in the eyes of this shark. The oldest type of poetryis poetry with a riddle inside.