All Your Sins are Free

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. If you like what we do, pay it forward and consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Readers here will have noticed I’m in the midst of a series on the Book of Revelation.

Despite the ubiquity of doomsday hucksters and pulpy Left Behind movies, if the gospel is true and the cross is to be trusted as a complete and finished work, then the same refrain which announces the beginning of the work of God in Jesus Christ occasions the Fulfillment, as well as our place in it, “Do not fear.”

The headline the angel Gabriel gives to the gospel abides to its very end.Death need not be feared—no matter the nature of the life that preceded it—because the good news of the gospel is that the character of my life or your life is not the good news.

The god who dies in Christ’s grave never to return is the angry god conjured by our angry hearts and anxious imaginations.

If it’s the devil in the desert who speaks in if/then conditions, then the devil’s chief work in the world is to convince us that our sins are more consequential than Christ’s complete and total triumph over them.

This is why St. Paul in his long argument on the resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15 is so adamant about the absolute necessity of Christ’s empty grave; otherwise, Paul insists, our faith is futile and our hope is pitiful. If the wages owed for our unrighteous ways in the world is the grave, then Christ’s empty grave is the sure and certain sign of the opposite: his perfect righteousness.

His resurrection is the reminder that his righteousness is so superabundant its paid forward for all the wages of our every sin.Thus, there are no wages left to be paid for any of your sins. Easter’s empty grave is the sacrament, the outward and visible sign, that in Jesus Christ you have been prematurely and permanently exonerated. In Christ, God became a goat, separated and forsaken from the Father, left behind in a hastily hewn grave, so that you could be counted among the flock forever. The End, therefore, or just your end, is not an occasion for fingers-crossed fear or fretful hand-wringing because when Christ returns, or you return to him, he will greet you already bearing your every sin in his cross-shattered body.

Thus, all your sins are free.From Good Friday forward, all your sins are free.

There is no cost to any of your sins other than what they cost your neighbor. You can dishonor your father and your mother, if you like. You can forgive somewhere south of 70x7 times. You can begrudge a beggar your spare coin. You can cheat on your wife or covet your friend’s wife. I personally wouldn’t commend such a life but such a life has no bearing on God’s Fulfillment. Such a life has no bearing on how God regards you. Of course, the world will be a more beautiful place and your life will be a whole lot happier if you forgive those who trespass against you and give to the poor, if your love is patient and kind, un-angry and absent boasting. But God loves you not one jot or tittle less if you don’t do any of it.

“It rains on the righteous and the unrighteous alike,” Jesus teaches in the Gospels and, imagining ourselves as the former instead of the latter, we always hear that teaching as the “offense” of grace. But turn the teaching around and you can hear it as Jesus intended for his flock to hear it, a different sort of offensiveness: God will bless you even if you’re bad.

God will bless you even if you’re bad.Again, the god who dies in Christ’s grave never to return is the angry god conjured by our anxious hearts, fearful imaginations.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that the good works you do for God and for you neighbor don’t matter. Rather, it’s that even the best good works of a Mother Theresa are a trifling pittance compared to the perfect work of forgiveness gifted to us by the baptism of Christ’s death and resurrection. “For freedom Christ has set you free,” Paul declares to the Galatians. He’s freed you, in other words, from the burden of living up to God’s commands. And he’s freed you from the fear of failing under them. For your performance according to God’s commands, all the accusing oughts and expectations of the Law, there is neither punishment nor reward.

Martin Luther wrote that the Devil’s chief work in the world is to convince us that this or that sin we’ve committed— or are committing— disqualifies us from God’s unqualified grace and his free, no-expiration-date, forgiveness. If Luther was right (and you can take those end times evangelists as Exhibit A), then the Devil is no place more active than in Christ’s Body, the Church.

The Devil’s primary mode of attack comes at believers through other believers. The Accuser gets at us through those freedom-allergic believers who take our sins to be more consequential than Christ’s complete and total triumph over them.You’ll hear such believers insist that the freedom Paul extols is really the freedom for you to be good and obedient, but this isn’t the Gospel it’s cognitive dissonance. Likewise, you’ll hear these tight-sphinctered pious types say things like “Yes, grace is amazing but we mustn’t take advantage of it.” Such holy types are afraid of the freedom the Gospel gives you. They’re worried that if you don’t have to worry about incurring God’s wrath and punishment by your unfaithfulness, then you’ll have no motivation to be faithful, to love God and your neighbor. Without the stick, the carrot of grace will just permit people to do whatever they want, to live prodigally without the need to ever come home from the far country.

As easily as we swallow such objections, I don’t buy it. Speaking just from the mission field of my own life, I can testify that most of the damage I do to myself and to others isn’t because I’m convinced God doesn’t condemn me for my sins but because I fear- despite my faith, I still fear- the judgement I think I deserve. And so I do damage, making others the object of my anxious attempts to make myself look better and be better than I really am. I think this explains why the people against whom we sin the most are the people we most love. They’re the ones who’ve invested the most in us and we in them; consequently, we want to impress them the most and, as a result, they become the ones against whom we most sin. But not even a stranger or your enemy deserves to be the occasion of your project of self-justification; what’s more, no friend or family member can endure the burden of such an expectation.

The hilarity of the gospel, though, is that the news that all your sins are free actually frees you from sinning.Take, as just a rather obvious example, Jesus Christ: the only guy ever on record convinced to his marrow of the Father’s unconditional love. And his being convinced that God had no damns to give led him to what exactly? To live a sinless, self-less life.

That Jesus was without sin was the consequence not of his goodness and perfection but of Jesus’ perfect trust in the goodness of his Father.

In the foolish economy of his love, God has flooded our marketplace with an abundance cheap— no, free— grace, leaving our reliable currency of credits and debits worthless. God’s zeroed out the earning power of sin.That which is free has no purchasing power. God’s de-incentivized our consumption. No longer do we have any reason to window shop and browse around in the sins of others. They’re not worth anything. Nor are they worth anything to us. Our neighbors’ sins do not improve our own futures market. They do not increase by even a dime the value of our own portfolio because in God’s economy of grace our virtue likewise is an empty commodity, as antiquated as bartering with sheep and goats.

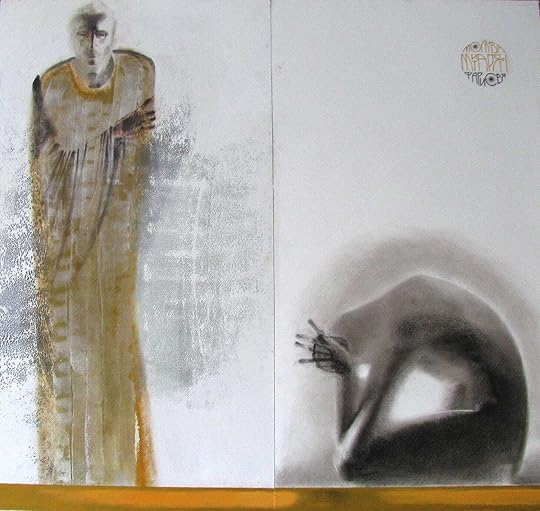

If all our sins are free, our virtue is without value.We’re bankrupt, beggars all, no distinction, without any need to put on masks and pretend we’re anything other than ourselves. If all our sins are free, then we’re back in the same position as Eve and Adam before there was a single one of them, without any reason for shame or blame, with no need to hide from one another, free to be seen and to be known, content to be creatures of our three person’d Maker.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers