The Syderstone Investigation, Part 1: The Ghost Hunters Gather

There’s an unusual amount of historical material available regarding an 1833 ghost hunt held at the parsonage in the hamlet of Syderstone, Norfolk, England. The head of the haunted house was a clergyman named John Stewart, who described the unaccountable manifestations as tapping and scratching, groaning and sobbing, and tramping and knocking. The latter noises became particularly loud. The phenomena, strictly auditory and heard in every room, had occurred ever since the Stewarts had arrived, and the curate says he had traced the haunting back sixty years! Indeed, the disturbances were continuing when he described them in a letter dated 1841, eight years after his family had taken up residency.

When the ghost hunt occurred, the alleged haunting had made its way into the press already. The May 6, 1833, issue of London’s Weekly Dispatch is the earliest report I’ve found. According to the article, the inexplicable knocks, moans, clangs, and crashes, were on the rise, “becoming more violent” and scaring away one servant. The ruckus began nightly at 2:00 a.m. and continued until daylight. Numerous witnesses confirmed them, and “several ladies and gentlemen, to satisfy themselves, have remained all night,” all to no avail. Equally futile were Stewart’s efforts to communicate with “the supposed ghost” and “to exercise his spiritual authority to exorcise it.” This report then spread to other papers, drawing attention across Britain and eventually across the Atlantic.

As hinted at above, Stewart encouraged investigation at first. In fact, he organized a formal probe to be held on the night of May 15/16, 1833, and this sparked a series of newspaper articles that provide the bulk of what is known about the case. One key article (see below) lists the people who Stewart summoned to form the investigation team and the towns from which they came. With the help of an 1836 Norfolk directory and a few other sources, I double-checked where they lived while adding first names. The investigation team was comprised of:

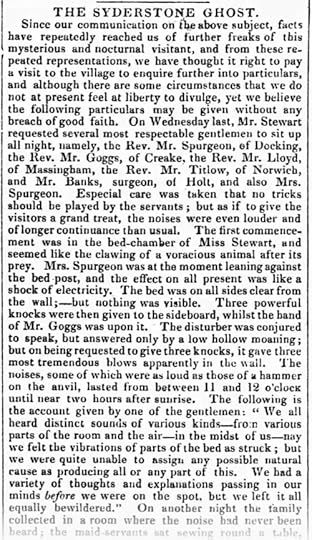

the Reverend John Spurgin, who traveled from Docking;Maria Spurgin, née Dewing (so named in this source and this source), who presumably accompanied John, her husband;the Reverend Samuel Titlow, who came from Norwich;the Reverend Henry Goggs, who came from Creake;the Reverend John Lloyd, who came from Massingham according to the newspaper, but resided in Hindolveston according to the directory of three years later; andJohn Banks, a surgeon who came from Holt.Stewart gives a brief description of the ghost hunt in a letter written a week afterward, which is reprinted in Elliott O’Donnell’s Ghostly Phenomena (1910). But more details were publicized in the May 29, 1833, issue of The Bury and Norwich Post. Here it is:

The report goes on to describe additional experiences of the family and household staff. It ends by acknowledging “the respectability and superior intelligence of the parties who have attempted to investigate into the secret” while also assuring readers that a physical cause will be discovered.

In the weeks to follow, both John Spurgin and Samuel Titlow publicly stated that this report was exaggerated. Sure enough, they had heard a series of knocks — some that matched the number requested by investigators — along with a moan and even a scream! They didn’t deny they heard strange sounds that they couldn’t explain, but they simply wanted it known that these weren’t quite as dramatic as described in the Post article.

Spurgin’s and Titlow’s respective rebuttals also sparked a split between the two ghost hunters regarding where to focus future investigation. I’ll dive into this rupture in Part 2, but to better understand that, it’s helpful to look at what others were saying about the Syderstone haunting.

The Ventriloquist Theory and Its ImplicationsIn the June 9, 1833, issue of The Norfolk Chronicle, John Baker of Leeds proposed a solution to the mystery: ventriloquism. In a fairly long letter to the editor, Baker opens by saying he was hesitant to offer his theory in the hope that something more certain would come to light. Since it hadn’t, he describes a situation that had occurred in his own house twenty years earlier. A quiet knocking was heard at night, disturbing the servants. Thinking it might be a rat, Baker and his staff then heard “a noise as if that animal was biting the boards.” That would have settled things, but the nightly disruptions grew louder. Baker says that

the rapping was like wagging of the tail of a pointer dog against a door, and the scratching like that of a cat against the boards violently -- the noise was too loud for a rat.... I was, I confess, rather 'bewildered.'And yet Baker suspected one of his servants was the culprit. Interestingly, he says he wanted to find out if she was “a ventriloquist,” not a hoaxer or a prankster. He then conducted a series of simple tests, the last of which

fully satisfied me that the whole was done by this person, she having the power of ventriloquism or conveying sounds to a distance.... I discharged the servant and we were no more troubled by the Ghost.Baker concludes by declaring his conviction that “the Syderstone Ghost is a ventriloquist….” However, since the Post had already reported that the members of the May 15/16 ghost hunt were drawn to activity “in the bed chamber of Miss Stewart,” there’s a serious implication here, especially for a clergyman in 1833. Baker was not simply pointing out that there is nothing supernatural happening in Syderstone parsonage. Neither was he exactly suggesting the noises there spring from a mischievous servant, one who could be promptly dismissed. No, given the ghost hunters’ findings, Baker’s implication is that the haunting is a deception created by one of the respectable Stewarts.

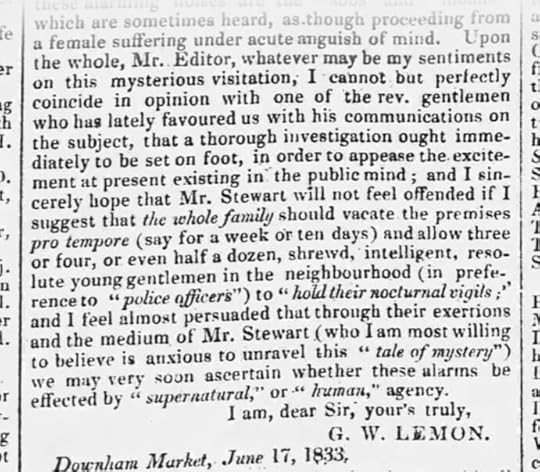

This explains why G.W. Lemon wanted to launch in his own investigation — with the family absent. In the June 19, 1833, issue of the Post, Lemon explains that he visited the Stewarts to see if he could conduct his own ghost hunt. He was refused because “the family had been so much harassed of late by acceding to the wishes of the public, that they had been as it were compelled to decline the admission of of any further nocturnal visits.” Nonetheless, the Stewarts told Lemon of continuing disturbances that the papers hadn’t yet reported. Creaking footsteps heard in the attic had descended to the curate’s bedroom. A crash had sounded like some heavy metal object falling through the roof, and another one seemed to be a door “wrenched from its hinges and hurled with violence against the floor.” All the while, sobs and moans were heard.

Still aching to investigate (and very likely referring to a letter-to-the-editor written by Titlow), Lemon ends the letter this way:

If the phenomena ceased with the Stewarts away, they would be implicated, and if it continued, they would be exonerated. But there was another way to determine the Stewarts’ innocence. What if it could be shown that the phenomena had been witnessed before the family ever moved in?

Testifying It Wasn’t Someone in the FamilyThe Chronicle did exactly that in their June 22, 1833, issue. An article signed by Thomas Seppings and John Savory presents testimony from five people who had served previous clergymen at the parsonage, a visitor who had slept there, and a shepherd who — while walking by when the place was unoccupied — had heard “very loud ‘groanings’ like those ‘of a dying man'” coming from deep inside. Seppings and Savory open by saying that the witness accounts were collected to inform the public as well as to protect the Stewarts from “the most ungenerous aspersions….”

Other than what the shepherd reported, the witness evidence becomes a bit repetitive in terms of noises heard but never explained: knocks, crashes, a door opening, furniture dragged, and glass and china rattling. You can read the full report here. What’s more important is that Syderstone parsonage had been a site of unusual, if not ghostly, phenomena for about twenty years before the Stewarts arrived.

However, Samuel Titlow, one of the May 15/16 ghost hunters, refused to rule out the possibility that a family member had a hand in creating the weird noises. On this point, he sharply differed from his co-investigator John Spurgin. How they made their disagreement very public is discussed in The Syderstone Investigation, Part 2: The Ghost Hunters Divide.

Part 2 will be posted on Sunday, October 1.