Remembering The Count of Florida’s Panhandle

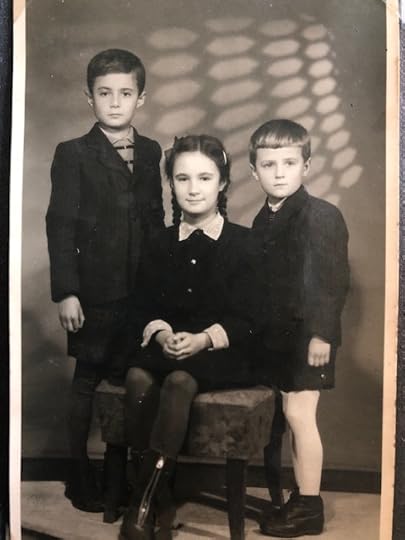

My father (left) and his siblings

My father (left) and his siblings“I am a Cejka,” my father would often announce, as if all of us should know what that means, other than recognizing that it is his family name.

The communists had taken over Czechoslovakia when he was a boy, stealing his family’s estate and fortune, but my father continued to carry with him a sense of pride about being a Cejka. One he took with him from the cold water flat he shared with my mom in Prague, all the way to his simple, one-room rentals in Chicago. He strode the public beaches of his retirement state of Florida with the imperious detachment of a noble surveying his lands.

As a child, I had a fascination with my father, and this high-falutin’ family of his. The dichotomy between the way he lived his life, and the Downton Abbey circumstances of his birth couldn’t have been starker, and his eccentric behaviors were the stuff of legend in the Czech immigrant community.

How he hated to bathe.

His pathological obsession with being in the outdoors.

His extreme miserliness.

The crazy sh*t he would say.

The stories about him were the only way I knew him throughout most of my girlhood. My parents divorced when I was a baby, and right around when I entered Kindergarten, my mom married a man who would raise, and later adopt me, effectively erasing my father’s physical presence from my life.

I did have some tangible memories of visits with my “bio-dad,” as I called him. I remembered that he introduced me to banana ice cream and taught me how to ski, for instance. But between about age five and age eighteen, I saw him only once.

That visit was a strange and awkward lunch orchestrated by my mom, when I was about twelve years old. She spent much of the hour or so we sat in a nearly empty diner, specifying all the ways in which I resembled the Cejka family – my brow, my jawline. She pointed to the knuckles on my hand, comparing them to my father’s. I felt a bit like a “thing” at that lunch – constantly being referenced, but never really engaged.

“You nervous?” I remember my father saying, and then he laughed.

Until that day, my mother had advocated for a persona non grata policy towards her ex-husband and father of her children. With no further explanation, she went back to that policy, as if our weird little interlude never happened.

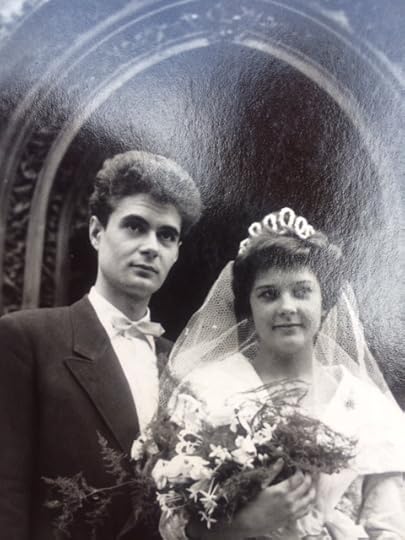

My parents on their wedding day

My parents on their wedding dayThen, out of the blue, when I was eighteen, my brother called me up with a proposition.

“Want to have lunch with Tata?” he asked me. “You don’t have to, but I should tell you I’ve started seeing him again, and I thought you might find it interesting.”

I thought about it for a few seconds, just to assess where my gut feeling stood on the prospect of opening what was, potentially, a can of worms. I knew my mom hoped we would never see our father again, and she truly had not a single, positive word to say about the man. She wasn’t the only one. And I’d tried this lunch business one time before.

Yet without hesitation, I said, “Yes.”

And so began a rather curious relationship. A father-daughter bond that was based not on shared memories, communal values, or anything resembling love. It was a bond of family history, of missed opportunity, of ghosts, and of oddities. It was also, at its core, an animal bond of blood.

My father, brother, and me, along with our cousin’s young daughter in Slovakia

My father, brother, and me, along with our cousin’s young daughter in SlovakiaAfter a first, self-conscious meeting in my father’s attic apartment in suburban Chicago, where I was shown family photos, and my father strummed Czech folk songs on his guitar, we settled into a routine that suited us both: dinner and a movie. Typically, my father and I would meet at a Czech restaurant, since that’s the only food he liked, and then rifle through the theater listings.

Our dinner conversations were quirky, but easy, and mostly centered around his visits to the old country, nature, opera (but only if it was Czech opera), and the Czech immigrant dances he liked to frequent.

As we moved on from restaurant to cinema, the conversation would continue as if we hadn’t changed venues at all.

Uninterested in stories that weren’t by or about Czechs, which is the vast majority of them, my father would speak loudly about random topics during our film of choice, provoking shushes and dirty looks that he was completely oblivious to. In a packed theater for the 1995 Brad Pitt vehicle “Seven,” things almost came to blows when my father wouldn’t stop complaining about the absence of “beautiful nature” in the film.

“Look at it – it is terrible,” he called out. “There are no mountains, no lakes, no nothing! Just ugliness!”

Then there were the “dates” when we wouldn’t even make it to the movies at all. If the weather was good, my father would pull over to any body of water – no matter how dubious – strip naked, and go for a dip.

“Come in,” he would call.

I’d point to the prominent “No Swimming” sign and remind him that I didn’t bring my suit. My father would shrug and splash around, delighting in this interlude as freely as if he were a water bird.

Shouts of “Hey, asshole! Put some clothes on!” would blast out of car windows, and he wouldn’t even look up to see where they’d come from. He was in his own world, and despite the occasional embarrassment, I admired that about him. My father was a man without self-consciousness – an animal in the wild. It was only when he was outdoors – swimming, lying in the grass, foraging for mushrooms – that he felt any real kinship, a relationship to something other than his routine.

It was nice to see him happy.

On the rare occasions when my father would attempt to give me life advice, his counsel would take on the perspective of a 1950s public service announcement voiced by a crotchety Count Drakula.

Worried that I was twenty-nine and still single, he once berated me in front an entire restaurant. Banging his hand on our table, he shouted, “You have to face the facts! Women’s brains are smaller than men’s, and after age thirty you won’t be marketable anymore. You will dry up and your Cejka genes will die!”

“Poor, dry, mini-brained me – whatever will I do?” I sighed, putting my hand to my forehead like I was in need of a fainting couch.

“It’s not funny! This is your life!” He cried. He was in genuine anguish about the state of my affairs as a single woman and small business owner. My life as a college graduate and chocolatier, at the time, seemed to him to be a dead end, a failure.

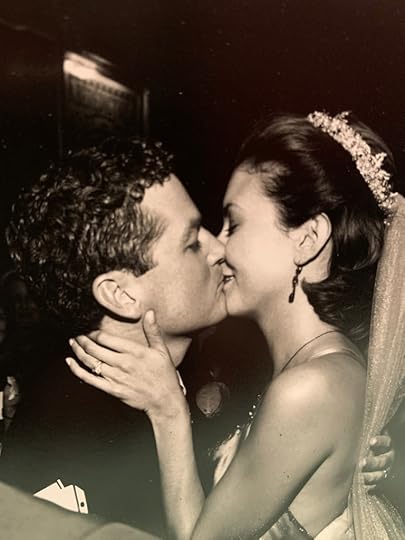

A day of great relief for my father

A day of great relief for my fatherBy the time I married, and my children were born, my father had retired from his job as an electrical engineer and would drive down to see my family at our home in Virginia. His visits were characterized by their surprise nature – he never called in advance to tell us he was coming – and his hygiene. On his first drop-in to our new house, in our new state, I found that he’d stopped bathing entirely, except in lakes or streams.

“I like to smell like the earth,” he was fond of saying. “And I don’t have to go to work anymore, so who cares?”

“People who have to sit next to you care,” I told him.

But his unusual behavior was always tinged with a bit of romance and culture with a capital C. He would play passionate Dvořák concertos on our piano – beautifully – only he’d do it at 2:00 a.m. and seem genuinely perplexed when I would come downstairs and ask him to give it a rest.

“The kids have school tomorrow, Tato.”

“They should listen to the classical Czech composers,” he’d say, dismissing me. “They are the best.”

“Well, of course,” I said. “But couldn’t they do it in the afternoon?”

My middle daughter, Charlotte, never quite got over the fact that her grandfather gave her a dirty, broken moose keychain that he found on the side of the road, for her eighth birthday. “It works perfectly fine,” he said.

Or that he kept calling her Scarlett, no matter how many times she corrected him.

Yet once a year, he sent us a $300 check, specifying that it was to be distributed equally between our three children – Eamon, Scarlett, and Josephine, and my husband and I were not to use any of it for ourselves.

“Do you honestly think I would steal the Christmas money you sent to our kids?” I teased.

“How would I know?” he said. “I didn’t raise you. And you are only half Cejka, although you seem to have many of our excellent qualities.”

The midnight concert visit

The midnight concert visitThose “excellent qualities” he identified as “being cleverish,” my writing ability (a 19th century Cejka was sort of the Czech Emerson), and my enthusiasm for physical fitness (Cejkas are hearty, he told me). While our actual personalities had all the common properties of chalk and cheese, I couldn’t help appreciating his cockamamie perspective on things.

“I can’t believe you see that idiot!” my mom would grumble.

She considered the day her divorce was granted as the happiest day of her life and couldn’t fathom why we’d reconnected with our father. Especially when she felt like she’d gone to such lengths to spare us from him.

“There’s something wrong with that man,” she said. “Everyone knows it.”

She had a point. My brother, a clinical psychologist, believed a “right brain disorder” could have been at the root of our father’s more peculiar behaviors. Ones that got him into trouble here and there – getting a beer bottle broken over his head or getting fired for insulting his boss. He had a way of blurting out the sorts of observations most people keep to themselves. If they know what’s good for them. Things like, “Your wife is very ugly, but perhaps she is a good cook, so it doesn’t matter to you.” (Yes, he actually said that.)

Cejka family pyramid, Czechoslovakia 1975

Cejka family pyramid, Czechoslovakia 1975His candor was second only to his miserliness, and the two often found themselves in good company. My father was known to crow about how he’d gotten out of paying child support by letting my step-dad adopt my brother and me. In the same breath, he’d tell me how he felt cheated out of a relationship with us, and blamed my mother for that. Not for bad-mouthing him, but for reporting his delinquent child support payments to the court.

Yet, he continued to be in love her for the rest of his life, and wouldn’t even consider remarrying, despite several long-term relationships.

“I am already married,” he’d say. “And a wife costs money.”

My father at our place in Virginia a few years ago

My father at our place in Virginia a few years agoMy father took a great deal of pride in the fact that my brother and I had continued the Cejka line, yet our efforts to help him integrate into our lives, and into the lives of his grandchildren, largely fell flat. Or rather, they would begin with a certain level of enthusiasm, then fade away like a temporary tattoo. While our father indicated he wanted to be a part of our lives, and was clearly lonely, his solitary nature chaffed at the idea that he might be held responsible for something as simple as remembering birthdays.

In the last few years of his life, he became particularly distant from us, communicating mostly by intermittent email, with his surprise visits becoming fewer and farther in between. Still, we all kept trying – clumsily perhaps. None of us were inclined to give up, sever the tie. In the absence of love, we had been given a sense for the unorthodox gift of a misfit relative. Of the tolerance and self-control a difficult person forces us to utilize, internalize. How they help us grow and provide comfort and companionship to a person who genuinely doesn’t know how to accept such an offer. That was enough.

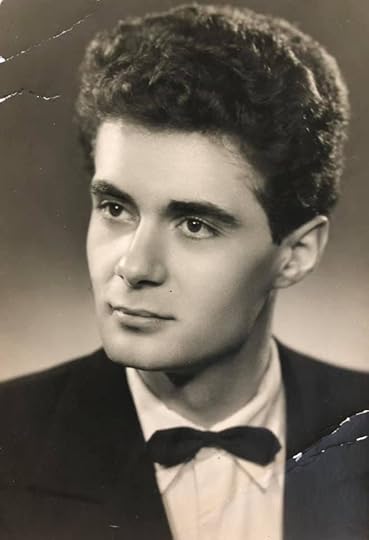

The look on his face here speaks of loneliness to me

The look on his face here speaks of loneliness to meThis was why, when I took my then thirteen-year-old son, Eamon, to Prague on an adventure to the old country, I was determined for us to spend a day or two with my father. Even if I knew those would be long days, indeed. Especially for my kid.

My father, who by this point was dividing his time between the Czech Republic in the summer months, and Florida in the winter, wanted very much for us to stay at his house in his birth village, Třebíz.

Except that the place was run down, smelled of mold and animal waste. Neither the kitchen nor the bathrooms worked properly, and only the yard, which was nice and contained an orchard, was in good condition.

“Please let’s not stay here,” my son begged. “It’s creepy.”

Notwithstanding my usual can-do attitude towards my father, I caved without a second thought, and I don’t think my father ever quite forgave me for staying with family friends close by. He felt I’d robbed him of time with his grandson and chose outsiders over blood.

My son and father in Třebíz

My son and father in TřebízBut we had some magic with him on that trip, too. At a bookstore reading of my novel, The Bone Church, a historical thriller set during the Cold War, my father was the star of the Q & A session. For the first time, he recounted his version of my parents’ escape from the communists, and he did it with a vim and vigor I’d never witness in him outside of nature.

He told the crowd how they’d plotted to obtain permission to take a vacation to the Black Sea, after they’d learned their train from Prague had a stop on the porous border between Yugoslavia and Italy.

Just like in the movies, he found himself crawling to freedom through a field of grass, until he came upon a pair of boots. His eyes followed all the way up the body of a pugnacious border guard, and he came face to nozzle with a gun, nearly pissing himself.

“We claimed to be lost,” he cried. “Saying we were in Yugoslavia on vacation and didn’t know our way around. And your mother, she cried and beg, and she was nice looking, and I think they feel sorry for her. They yell and point their fingers – ‘If we see you here again, you’re going on the next train back to Prague, and they’ll probably throw you in prison for a long time.’ It was all very scary.”

But my parents didn’t give up. My mother traded all of her money and belongings for an Italian couple’s passports. She did her hair like the woman, and my father wore a hat. My brother was too young to need identification and was instructed by our parents to pretend to sleep.

“Thank God the border guards didn’t speak Italian to us,” my father said. “I would have no idea what he was talking about and we would be in jail for twenty years.”

That great escape was the one true triumph of their marriage. Possibly the only time they’d worked together for a desired outcome and emerged successful. And he savored it.

My son, my father, and I, at my book reading in Prague

My son, my father, and I, at my book reading in PragueIn the years following our Prague trip, my father became more untethered. During his summers in his birth country, he lived in his village house, which according to my cousin, had become unlivable. It had been infested by a family of voles and the kitchen and bathrooms smelled awful and were completely derelict by then. My cousin offered to fix up the place – knowing how tight with a coin he was – but my father refused.

“It’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with it,” he told her.

His winters in Florida were spent entirely in the outdoors, mostly on beaches or in state parks. My brother and I tried to convince him to buy a small apartment, or rent one, but he was adamant that no, he preferred to sleep in his car. He wanted to be free, he told us, and he thought an actual home was a huge waste of money.

“My father has become, for all intents and purposes, homeless,” I told my husband.

With the onset of COVID, my father had to cancel any plans to visit Prague, and was fixated on his health, frightened of getting the virus. While a very fit eighty-one, he’d been having some age-related health issues that concerned him, too. Once again, I asked him to visit us, but he refused.

“I am old man, now,” he said. “It is an inconvenience to me to have to drive up there.”

“You could fly,” I told him. “We’ll buy you a ticket.”

But that was a no-go.

I’d send him pictures of my family, and he’d remark about how big my children were getting, occasionally identifying qualities that he recognized as having Cejka origins – curly hair, dark skin, the thick, determined brow that all of us seem to share. But he never gave much information about himself, even when I made specific inquiries about his life and sent him a detailed update of our exploits.

My father seemed melancholy. An email I received from him on September 14, 2020, read, “I hate this Corona virus and it is worse for singles like me.”

“I know,” I replied. “I hope we get a vaccine soon.”

My father emailed me this picture from Boyton Beach in fall, 2020

My father emailed me this picture from Boyton Beach in fall, 2020In mid-November of the same year, a couple of weeks after he’d last reached out to us, a police officer came to my brother’s house near Gainesville. Our father had been tested for Covid and had left my brother’s address with the clinic. The officer was concerned because the clinic had indicated he’d seemed quite ill and had indeed tested positive for the virus.

After a missing endangered persons report was filed, our father was finally located through his cell phone, and the police did a drive-by of where he was staying: a rented, one room camper on a country property, just a dash from a small lake he could bathe in.

Delirious and dehydrated, he was taken to the COVID unit in a local hospital, and from then on, our only contact was with the staff that was caring for him.

Although he was in pretty bad shape when he arrived, the doctors still told us they thought he would pull through, given how strong and fit he was. They dubbed him “The Flying Wallaby” for his propensity to lift himself up by the guard rails on his bed. It was when he started doing somersaults in that bed that the doctors finally had to sedate him and take more drastic measures. But they were to no avail.

A week later, my father died.

The nurse who had taken care of him in his last days held his hand when they took him off the ventilator. She assured us that he slipped away peacefully, and almost immediately.

My father’s final visit with my family

My father’s final visit with my familyAlthough our father’s presence in our lives had been sparse and floundering, his sudden absence was destabilizing and unexpectedly sad, for both me and my brother.

“He was such a part of your story,” my best friend told me.

He was.

We wanted to know what happened in the days preceding our father’s illness, knowing how fastidious he had been about his health, if not his hygiene. He’d had a full work-up at the Mayo Clinic just a couple of years prior, and had an appointment for a colonoscopy scheduled for the week after his death. He mentioned COVID in every one of his brief updates, so he was clearly aware and motivated to be cautious.

My sister-in-law did some digging.

She learned that a bar he’d frequented had been closed due to a COVID breakout, and that was likely where he’d caught the virus. My father had always loved dive bars and was an odd-ball regular character at a couple of places in the panhandle that he frequented. A place called Catfish Jack’s was his favorite.

Turned out, my father’s fear of COVID had not been enough to keep him from trying to stave off his loneliness. He couldn’t resist going into bars, which apart from nursing homes, had shown some of the highest rates of transmission. Family was important to him objectively, from a genetic standpoint, and he may have longed for us all from time to time, but when push came to shove, he felt most comfortable in the company of virtual strangers.

My father and a lady friend at a Czech dance a few years ago

My father and a lady friend at a Czech dance a few years agoStill, it breaks my heart that he died without any of us at his bedside. Blood relations, as he would say. Cejkas. I suppose it’s some consolation that my brother and I were always afraid that his end would be worse. That he might be found weeks after his death – in a national park somewhere, his body already decomposing.

We worried he could fall victim to foul play, as he rarely locked the small van that was his home most nights – a vehicle he’d tricked out with a foam mat and DIY screens that allowed him to roll down the windows to allow for fresh air while keeping out the bugs. He liked to lay there listening to Czech opera on the stereo, looking up at the stars through his moon roof.

When my brother and his wife went to get a look at his rental camper, the last place he’d actually lived for any period of time, they said it was even farther out in the middle of nowhere than they thought. So far out that everyone who saw them driving in came to get a look at the outlanders in their midst. Upon closer inspection of his living conditions, they discovered my father’s car was filthy, as was the camper. He’d been living in squalor.

My sister-in-law was able to hold it together until she and my brother got back into their car and started driving away. Then she broke down in tears.

“I’m actually going to miss the crazy bastard,” she told me on the phone later.

That’s generous of her, considering that my father had always flagrantly excluded her children from her first marriage from any attention or gift giving. My brother had adopted his wife’s kids, raising them alongside his biological children as if they were his own, but that didn’t hold much water for our father.

“They’re not Cejkas,” he’d said.

Part of the one-time Cejka family estate in Třebíz, CZ

Part of the one-time Cejka family estate in Třebíz, CZWe decided to cremate our father’s remains. It made sense on many levels. Covid-wise, certainly, the fact that our father wasn’t religious played a role, and that he valued the least expensive option. He stated as much in his will.

Our cousin in Slovakia requested half of his remains, so she could bury them in Třebíz. We thought this was an excellent compromise and would honor the things he most loved.

As soon as we’re able, my brother and I pledged, that with our families, we would scatter our portion of his ashes in the nature areas he most enjoyed frequenting in Florida. Where he thrilled to the fresh air, the cool water, the sand between his toes, to suck on blades of grass, and nap in the shade of a tree heavy with leaves. He loved those things more than people.

The other half of him will be with his blood in the Cejka family burial ground. Because he loved being a Cejka most of all.

Jan Cejka, RIP

Jan Cejka, RIP