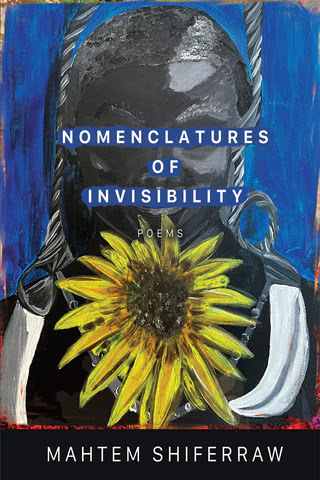

Mahtem Shiferraw, Nomenclatures of Invisibility: Poems

The Eucalyptus Tree I

after Susan Hahn

I long for it on quietnights and call it

home. It stands tall andmuscular

above the mountains. It seesme

but does not flinch. It feedsme

honey and wild winds. It callsme

child, though I do nothear.

Its leaves, a balm forblistering skin;

what comes after a cry, or bleeding?

Its aroma, like autumn,like rain,

stands green, translucentthing,

between my father and I,and the ghosts

of Gojam. It sees us: bleeding.

We carve wombs throughoutits roots

and rest our littlebodies. We bear

children the size ofseeds and fold

them into our brancharms. The rings

of fire that embrace usare blue with fear.

Everywhere we go, wesmell of death

and something sweet.

Thethird full-length collection by Mahtem Shiferraw, “a writer and visual artistfrom Ethiopia and Eritrea,” is

Nomenclatures of Invisibility: Poems

(RochesterNY: BOA Editions, 2023), following

Your Body Is War

(University of NebraskaPress, 2018) and Fuchsia (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), which wonthe Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets. There is such a clarity, a concretenessand precision, in Shiferraw’s lyrics. I admire the scaffolding of her poems,one that allows a variety of gestures, whether a hand in the air, or a story, apicture, all of which holds firmly together in a solidly constructed space. “Weare made with the same thing,” she writes, as part of the poem “Sawdust,” “and/ we hum quietly. He is a fish too, telling / his daughters stories of men withlurking eyes. / We swim elsewhere and find him staring / into the open skies.He asks, what are we / doing here? He asks, are we really here alone?” She writesof grandmothers, historical truths, colonialism and cultural arrogance; shewrites of cultural truths, inheritances and children. “To be able to set acrossthe ocean, / across unnamed seas and other waters,” she writes, as part of “Wuchalle,”“and / lands, and suddenly, having arrived at the // coastal states, suddenlynot noticing / the existing communities, and instead, / deciding to takeownership—like that, / like that.” She writes what is seen and known and notknown in searing lyric, offering a clear through-line reflecting and meditatingon language, the self and the body in a cultural, communal and familial space. “Theseeds we plant are may, but / many more of us grow—,” she writes, to close thepoem “Crackling Blue,” continuing:

Thethird full-length collection by Mahtem Shiferraw, “a writer and visual artistfrom Ethiopia and Eritrea,” is

Nomenclatures of Invisibility: Poems

(RochesterNY: BOA Editions, 2023), following

Your Body Is War

(University of NebraskaPress, 2018) and Fuchsia (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), which wonthe Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets. There is such a clarity, a concretenessand precision, in Shiferraw’s lyrics. I admire the scaffolding of her poems,one that allows a variety of gestures, whether a hand in the air, or a story, apicture, all of which holds firmly together in a solidly constructed space. “Weare made with the same thing,” she writes, as part of the poem “Sawdust,” “and/ we hum quietly. He is a fish too, telling / his daughters stories of men withlurking eyes. / We swim elsewhere and find him staring / into the open skies.He asks, what are we / doing here? He asks, are we really here alone?” She writesof grandmothers, historical truths, colonialism and cultural arrogance; shewrites of cultural truths, inheritances and children. “To be able to set acrossthe ocean, / across unnamed seas and other waters,” she writes, as part of “Wuchalle,”“and / lands, and suddenly, having arrived at the // coastal states, suddenlynot noticing / the existing communities, and instead, / deciding to takeownership—like that, / like that.” She writes what is seen and known and notknown in searing lyric, offering a clear through-line reflecting and meditatingon language, the self and the body in a cultural, communal and familial space. “Theseeds we plant are may, but / many more of us grow—,” she writes, to close thepoem “Crackling Blue,” continuing:these ones erect andunapologetic

small conquerors of oldworlds—

though, they too, mustcarry the

weight of distraughtancestors

like heavy rocks, sinkinginto their bones

deeper and deeper

until their cracklingturns blue.