How the Magna Carta Came About

Episode 2 The Magna Carta: Patching Up a Squabble

1215: Years That Changed History

Dr Dorsey Armstrong (2019)

Film Review

Despite the Magna Carta’s reputation as the foundation of modern democratic legal systems, it had minimal impact on the rural peasants who comprised most of England’s population in 1215. Armstrong uses most of this lecture to lay out historical background to this agreement between King John I and 25 rebellious barons.

Following the Norman conquest in 1066, the Anglo Saxon barons who controlled most English estates had their lands seized by their new Norman overlords. Most of the Anglo Saxon barons who survived went into monasteries.

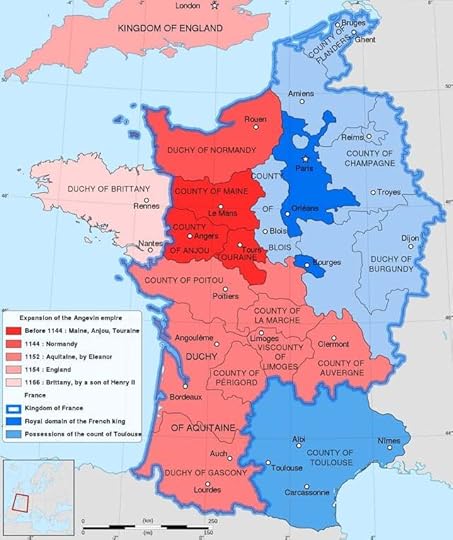

Following his occupation of England, William the Conqueror continued to control much of France.* However by 1215, John I was continuously at war with the French king to keep these lands. This, along without continual wars in Ireland, Wales and Scotland, led to massive tax increases, especially after the king lost many of his French holdings (and the revenue they produced).

In the 13th century, all English land technically belonged to the Crown, with large landholders paying the king a fee for growing crops on it (cultivated by peasant serfs). In addition to increasing these fees, John I also increased the fees sheriffs paid for the right to collect taxes (which they pocketed) in their assigned jurisdictions. King John also increased his income by aforesting agricultural land to increase his income from poaching fines.**

The rebellious barons were also angry about the king’s dispute with the pope about the former’s attempt to appoint his own Archbishop of Canterbury (the nominal leader of the Catholic church in 13th century England). To punish the king, from 1208-1213 the pope put England under an interdict under which no church bells rang, no masses were held and no English Catholic could be buried in consecrated ground. John I’s reaction was to seize the revenue of all England’s Catholic churches, for which the pope excommunicated him.

The pope repealed the interdict after John I accepted the pope’s appointment of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, signed over all his remaining empire (England, Anjou, Poitu, Gascony and Ireland) to the pope and agreed to pay Rome 1100 marks a year to remain king.

The barons’ initial demand was for John I to affirm the laws of the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor and to reissue Henry I’s charter of liberty. When the king refused, the barons renounced their allegiance to the throne.

After the king appointed a royal negotiator, the 25 barons drew up the 63 clause document (later referred to as the Magna Carta). The king signed it on June 15, 1215 at Runnymede.

A few month’s later, at the king’s request, the pope declared it illegal under church law.

*In addition to Normandy, Anjou, Poitou, Gascony the English king controlled Aquitaine (acquired after William the Conqueror’s great grand son Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. At the time, it was known as the Angevin Empire.

**Prior to 1066, forests were a commons, which meant it was legal for all British subjects to hunt enough boar and deer to feed their families. After the Norman conquest, the forest became the king’s exclusive property.

***John I’s father Henry II appointed – and later murdered – Archbishop of Canterbury Thoma Beckett.

Film can be viewed free with a library card on Kanopy.

The Most Revolutionary Act

- Stuart Jeanne Bramhall's profile

- 11 followers