Memories Straying Like Cows: My Unspectacular Progress in Adding to What We Know About Poe’s Final Days

The many mysteries surrounding Edgar Allan Poe’s demise have probably been baffling armchair detectives ever since the announcement of that death hit the papers in October of 1849. As I piece together my own timeline of what happened, I hoped I might stumble across something new or, at least, correct a mistake that has been repeated and repeated for decades.

Perhaps I was overestimating my ability to go all C. Auguste Dupin on this case. I’m sorry to report that, so far, I haven’t come up with anything of much importance. Yet it’s been interesting to see how those who were there changed their stories over time. Here are two examples of exactly that.

The Shifting Name of the Establishment on Lombard StreetOne of the oddest clues in the case involves Poe, typically a fastidious dresser, being discovered in shabby clothes and even shabbier mental condition. It happened on October 3, 1849, on Baltimore’s Lombard Street, between High and Exeter. A man named Joseph Walker found him there, and Poe was coherent enough to bid Walker to summon Joseph Evans Snodgrass, an editor with medical training. Walker complied, sending a message that identifies the location as “Ryan’s 4th ward polls.” This probably made sense at the time, given that there was an election going on and the spot was serving as a voting place.

But Snodgrass did not use that same name when, years later, he twice recounted the events for publication. His first memoir was published in something called Women’s Temperance Paper, reflecting Snodgrass’s devotion to the anti-alcohol movement. This source seems to be no longer extant. In January of 1856, though, the piece was reprinted in The Spiritual Telegraph, and we have a copy of this. (See page 155 or this transcript.) Snodgrass explains that, on receiving Walker’s message, he rushed to “a drinking house in Lombard-street, Baltimore.” He adds that the place had rooms available, so we seem to be talking less about a tavern and more about an inn or a hotel with a bar. Snodgrass doesn’t give us much more to help us pin down what kind of place it was.

Luckily, about a decade later, Snodgrass retold the story in Beadle’s Magazine. Here, the establishment is identified by name: “Cooth & Sergeant’s tavern in Lombard street, near High street, (Baltimore).” When I first read this, I was confused. I had seen other sources refer to it as “Ryan’s Fourth Ward Polls,” “Ryan’s inn and tavern,” and “Gunner’s Hall.” I hoped that sorting out this issue might be my small contribution to what we know.

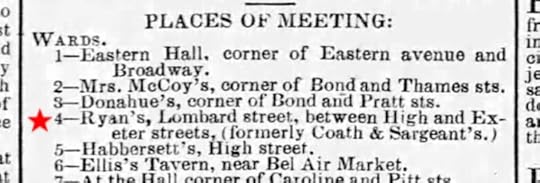

Well, here’s what I found. Baltimore newspapers reveal that — between October, 1840, and October, 1846 — there was a political rallying/voting place called “Cooth & Sargeant’s” or “Coath & Sargeant’s” on that city’s Lombard Street. However, by 1849, this had become its former name. Instead, it was known as “Ryan’s Hotel,” “Ryan’s,” or “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall.” (I suspect the hall was a meeting room within the hotel, one frequently used for political functions. It might also have been the barroom itself.)

It’s “Ryan’s Hotel” in The Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1849, pg. 2.

It’s “Ryan’s Hotel” in The Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1849, pg. 2. It’s “Ryan’s” and “formerly Coath & Sargeant’s” in The Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1849, pg. 2.

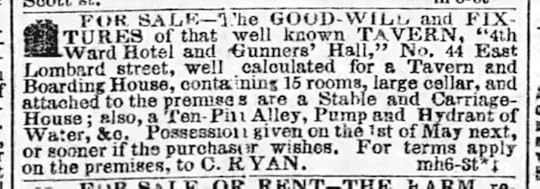

It’s “Ryan’s” and “formerly Coath & Sargeant’s” in The Baltimore Sun, November 27, 1849, pg. 2. It’s “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall” in The Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1852, pg. 4.

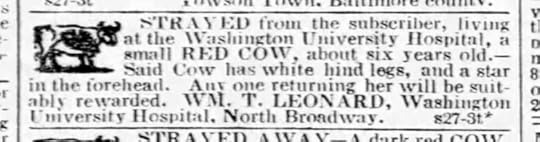

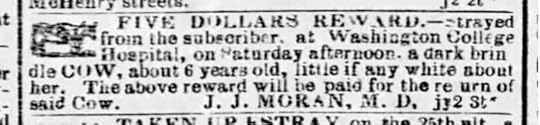

It’s “4th Ward Hotel and Gunners’ Hall” in The Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1852, pg. 4.I found a handful of inconsistent notices like these, so all I can safely deduce is that, by 1867, Snodgrass’s memory had simply wandered back to the location’s earlier name. He does the very same when he says that Poe was transported to “Washington College Hospital.” It’s a very minor error, but by that time, the facility was generally known as Washington University Hospital, as shown in an 1846 newspaper article, the 1848 notice for a stray cow shown below, and an official 1849 report.

One thing I’ve learned from investigating Poe’s death is that — at least in Baltimore — livestock strayed often enough that there were newspaper columns specifically designed to sort out adventuresome cows, horses, and hogs. This announcement appeared in The Baltimore Sun, September 27, 1848, pg. 3.The Disappearance of Reynolds

One thing I’ve learned from investigating Poe’s death is that — at least in Baltimore — livestock strayed often enough that there were newspaper columns specifically designed to sort out adventuresome cows, horses, and hogs. This announcement appeared in The Baltimore Sun, September 27, 1848, pg. 3.The Disappearance of ReynoldsAnother famous clue appeared once Poe was in his Washington University Hospital bed. In a delirious state, he referred repeatedly to someone named Reynolds. This tantalizing tidbit goes back to a letter dated November 15, 1849, roughly a month after Poe’s death. There, Dr. John Joseph Moran informs Maria Clemm, Poe’s aunt and mother-in-law, about his patient’s recurring fits. After one outburst, Poe rested, but Moran checked in on him later:

When I returned I found him in a violent delirium, resisting the efforts of two nurses to keep him in bed. This state continued until Saturday evening (he was admitted on Wednesday) when he commenced calling for one 'Reynolds', which he did through the night up to three on Sunday morning.Interestingly, the story changed when Moran recounted his experience for publication about 25 years later. In 1875, the only time he uses the name Reynolds is when he says:

I had sent for his cousin, Neilson Poe, having learned he was his relative, and a family named Reynolds, who lived in the neighborhood of the hospital. These were the only persons whose names I had heard him mention living in the city. Mr. W. N. Poe came, and the female members of Mr. Reynolds’s family.This paints a much calmer picture than Poe calling out the name over and over after being restrained by two nurses. Refashioning the story again in 1885, Moran makes no mention at all of someone named Reynolds. Now, he substitutes the name Herring where he had written Reynolds a decade earlier:

I had sent for his cousin, Mr. Nielson A. Poe, ... having learned that he was related to my patient; and also for a Mr. Herring and family, who lived in the neighborhood. [Nielson] Poe came as soon as notified and also the Misses Herring.Analyzing Moran’s wandering recollections a century later, W.T. Bandy concludes that “Reynolds was only a figment of Moran’s imagination” or, putting it more mildly, “just a mistake on Moran’s part, which he gradually corrected.” This certainly seems reasonable. And yet I really wish that “Reynolds” and “Herring” sounded more alike. Surely, Dr. Moran had several patients. Had some other delirious man shouted for Reynolds, and Moran confused them? Maybe so.

Another stray cow belonged to Poe’s attending physician, J.J. Moran. This appeared in The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1850, pg. 3. Curiously, though this appeared after the similar notice above, it uses the earlier name: Washington College Hospital.

Another stray cow belonged to Poe’s attending physician, J.J. Moran. This appeared in The Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1850, pg. 3. Curiously, though this appeared after the similar notice above, it uses the earlier name: Washington College Hospital.Of course, a fiction writer might idly speculate that someone named Reynolds had something to hide and, so, convinced Moran to carefully and cleverly change his story. Don’t tell anyone, but creating a fictional solution to this authentic mystery is why I’m looking into it.

For the time being, though, I really haven’t shed any light on the mystery of Poe’s demise. What I discuss above only shows that memory is a funny thing, and most of us probably knew that already. My work continues, then, to find something new to say about a very old, well-trodden mystery. There’s more to ponder on my page called “The Facts in the Case of Poe’s Demise.”

— Tim