lessons from chernobyl

1

I had the chance to go to Chernobyl, so I took it.

When people found out about my destination, there came the inevitable jokes – because, you know, nothing is so hilarious as nuclear radioactivity. (Black humor, remember, is a valuable coping mechanism.) I was informed that a “young lady” like me would “find herself with a lovely glow” , that the two-headed cows were considered a delicacy. I retorted that I hoped to come back with a superpower.

I started thinking about death.

It would be that kind of trip.

2

I was thinking about a blog post entitled Top 5 Regrets of the Dying. Written by an Australian nurse named Bronnie Ware, the post hit a collective soul-nerve, went viral, and landed her a book deal.

The most common regret, writes Bonnie, is

“I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

She writes:

….When people realise that their life is almost over and look back clearly on it, it is easy to see how many dreams have gone unfulfilled. Most people had not honored even a half of their dreams and had to die knowing that it was due to choices they had made, or not made.

It is very important to try and honour at least some of your dreams along the way. From the moment that you lose your health, it is too late. Health brings a freedom very few realise, until they no longer have it.

But what does it mean, exactly, to live a life that is “true to yourself”? I can’t help thinking that it’s a bit like telling people to “be remarkable!” Great concept, vague concept, so what does it mean in a practical, nuts-and-bolts sense?

To live a life that is true and authentic to who you are — to have the opportunity to do that — is to turn life itself into a work of art. Art is about the making of meaning. And as Seth Godin points out, “all artists are self-taught”. This doesn’t mean that you should commit to a life of pseudo-striving, or that you can avoid in any sense the blood, sweat, tears and turmoil, the ambiguity and uncertainty, the years of deliberate practice that go into the making of any artist.

But the meaning you create is your own, and how you convey that meaning to others depends on your unique voice and skillset.

3

My boyfriend and I spent a night in Kiev, then a guide and driver drove us out to meet up with the study tour. We ended up walking down a long road into a ‘zone one’ area, where a village had been evacuated shortly after Chernobyl. The houses had all collapsed. You saw remains of foundations, gaping holes in the ground where cellars had been.

We ran into some locals who were on a pilgrimage to the nearby cemetery. They told us – through a translator – how it had unfolded for them. They read about the Chernobyl “incident” in a newspaper – a couple of lines that referred to an accident at the plant. They began to realize it was serious when government buses appeared to take away the children, and then the adults, for what they were told would be a “three-day stay” at a nearby camp. The entire village was relocated.

We visited families in other villages who told us about the impact of Chernobyl on their lives, their health, their children’s health. Green Cross International was providing access to medical care and in some cases microfinancing family businesses. One family showed us their rabbit-breeding business, taking visible delight in the creatures, picking them up and fondling them and inviting us to hold them.

I wanted to know if these people were angry. To be kicked out of their homes. Watching their children grow up on contaminated soil, constantly sick, missing school.

The answer came back:

No. It is life in the Ukraine.

Back at the hotel, my boyfriend and I learned that, despite our late addition to the group, we had been granted permission to travel with them to “the forbidden zone” the next day and see the abandoned city of Pripyat. In a surprise twist, we were also going to see the nuclear reactor itself.

I’m not much of a drinker, but that night a man from Moscow showed me how to shoot spiced vodka – followed by a quick bite of pork and bread – and I proved an apt pupil.

4

Thinking about death can be beneficial. One psychologist writes about a study in which depressed people thought about death for a week, and became less depressed:

…because it also increased their interest in intrinsic motivations (relationships, self-growth, helping others), which stand in contrast to extrinsic motivations (fame, wealth, physical appearance).

…. psychotherapist Irvin Yalom has argued that people naturally avoid thinking about death because it hurts. But over time, such a heightened increased awareness that life could end causes an “awakening,” which leads people to adjust their values and time commitments. Specifically, people no longer are concerned with impressing others, or looking good, or even that new promotion. Instead, they are focused on doing what they enjoy, and living a free, authentic life.

There it is again: that idea of a free, authentic life.

“A life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

We’re not a culture that’s comfortable with thoughts of death, or anything else that causes discomfort; our initial impulse is to work or drink or have sex or spend money instead. We seek distraction and stimulation, and excel at finding both. At what price, though, to us and to others?

Could that be the difference between asking How can I get rich and famous and afford that new Mercedes and What can I create today that has resonance and meaning for me [and thus hopefully for others]?

5

To get to Chernobyl you get on a train that takes you out into a very pretty countryside. The nuclear reactor looms along the horizon like some prehistoric creature raising itself against the sky. To enter the plant we had to show our passports to guards at the gate, who matched them to the pre-approved names on their lists: I couldn’t help being reminded, in a bizarre and unsettling way, of getting into velvet-rope nightclubs when I was younger.

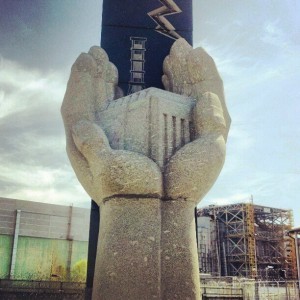

We were put on a bus and basically told not to take photographs of anything except the Chernobyl memorial.

Here is the memorial:

And then we visited the city of Pripyat, the former home of Chernobyl workers, now a ghost city in the Alienation Zone. We were told – again – not to step off the pavement, to avoid any contact with the vegetation. We were told not to enter any of the buildings. We saw what used to be a hotel, what used to be an arts center, what used to be an amusement park. Nature was reclaiming it all, spreading moss across the pavement and growing pine trees in the windows, profoundly indifferent to the absence of human life.

Later, we attended a memorial service in the city of Slavutich, which was hurriedly constructed to replace Pripyat and house a dispossessed population of roughly 50,000. It was midnight. I was standing and shivering in the middle of an open plaza. A crowd had gathered, shadowy figures in the near-dark, clutching votive candles and flowers. Ceremonial music began to play. A line of young people wound their way down through the square, carrying candlelit globes of a radiant fuchsia that picked out their progress in the darkness. They formed a human corridor and the rest of us began to drift along inside it, toward the front of the square where a shrine had been erected and dedicated to those who had died in the accident. The music stopped. The young people dropped to their knees. There was silence, and then the sound of sirens. A row of people dressed as Chernobyl workers took up position along the front of the shrine. The music began again, and Matt and I moved through the shrine and set down our flowers amid the candles, the photographs.

I was thinking about Chernobyl. I was thinking about 9/11, images of the towers, falling. I was thinking about the death of my ten-week-old son, from SIDS. I sensed the vast and collective nature of loss, of grief and trauma and suffering; we think we suffer alone, but we are mistaken. There are always others with us, moving slowly in the dark.

6

I saw a foreign movie once, years ago, in which a character proclaimed, “Life wants to live,” and it does. It will crawl through the cracks and grow in the windows. It will break through the ceilings so the sunlight gets in.

We live in relationship to each other, and to the earth itself. We forget this at our peril. We make art to remind ourselves of this: to illuminate — and question and challenge — those relationships. We take the truths of life that science can’t capture and put them into stories so that others may learn the lessons of conflict, struggle and disaster. If we can’t connect through these experiences, I don’t think there’s much hope for us.

To live a free and authentic life is to find a way to honor that small still voice within you, deeply personal and yet somehow universal. It is to stay connected to yourself, and through yourself to the human community. It is to create meaning from your experiences. I can no longer buy into the romantic drama of the isolated artist because art itself is connective. Without it, life becomes a ghost town, an Alienation Zone of one’s own.

Why we, especially as incredibly privileged Westerners, need the presence of death to wake us up to this –

We seem to need to deepen the darkness in order to find the light.

tweetable (click to tweet): we deepen the darkness in order to find the light