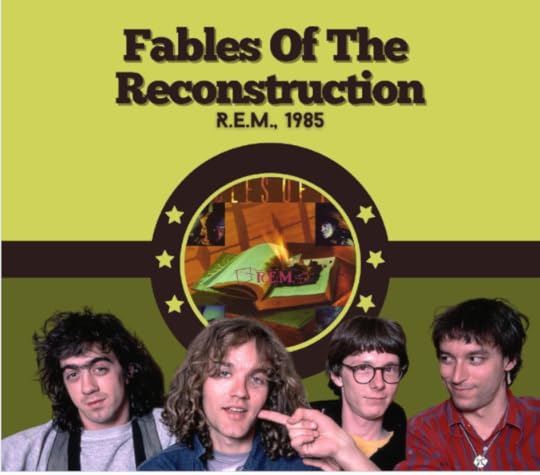

did r.e.m. create the modern indie rock album?

February 1985. R.E.M. gathered at Jim Hawkins Studio in their hometown of Athens Georgia. In about four hours they finished the 14-song demo that would serve as the starting point for their next full album. Joe Boyd, who was picked by R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck to produce the album, was sitting in the cramped but comfortable control room watching, listening. Boyd was a Harvard graduate who had gotten the music production bug in the mid-1960s. He was a direct connection to the old weird America folk rock music that R.E.M. was often compared to. In fact, Boyd had been the soundman at the infamous 1965 Newport Folk Festival where Bob Dylan performed his first-ever live electric set (the one where Dylan was booed by the audience). Now, twenty years later, as a 42-year-old independent music producer with his own fledgling record label, Boyd found himself in Athens watching the most popular college radio band in the United States. He was fascinated with what he saw and heard. R.E.M, was the past, present and the future of Rock, all in one band.

Boyd’s first bit of business was to convince R.E.M. to get out from under the watchful eye of their record company and venture across the pond to his studio in England. Peter Buck was onboard, and the other three band members quickly followed. Less than one week later Boyd, Berry, Buck, Mills and Stipes landed in a dreary, late winter, late-afternoon North London — not exactly the time and place that comes to mind when you think of old weird American folk rock. Nonetheless, R.E.M. entered Livingston Studio — a former church hall — to begin recording their third full-length album, Fables of the Reconstruction (alternatively referred to as Reconstruction of the Fables). A new genre was about to be born.

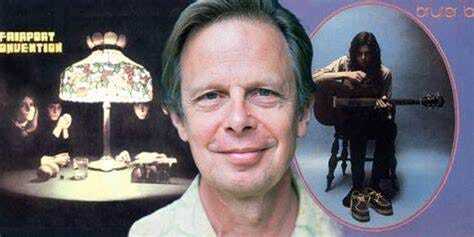

Rock journalists described R.E.M’s sound as new wave folk rock or jangly power-pop (Peter Buck’s guitar work was often compared to that of the Byrds), but these pundits also believed that R.E.M. had taken the college rock “little train that could” trail as far as it could go. It was a dead end to the middle of nowhere, and the members of R.E.M. understood this. They needed to head in a new direction. The most obvious trail would be to board a connecting train at their next stop and head straight down the shiny, happy pop music path into the commercial top 40/Mtv landscape of the mid-1980s. Peter Buck wasn’t thrilled with that prospect though, which is why he sought the input of Joe Boyd. Joe Boyd had produced non-commercial musical originators like Syd Barrett, Richard Thompson, Nick Drake. Boyd knew of an alternative route for the band and he entered Livingston studio like a train conductor enters a locomotive, gearing up to switch tracks for a detour. He prepared for a journey to a different route — a route in which R.E.M. could avoid that college rock dead end while also venturing away from that fatal, boring stop into Top 40 Commercialand.

Joe Boyd

Joe Boyd1985 was not an ideal time for the creation of a folk-rock masterpiece (or an album that would consequently be the genesis of an entirely new genre: Indie Rock). 1985 was the height of hair metal and Mtv poser bands and synthetic drums and voice effects and… well, you know — that entire era of shit-sounding production. The only way to hear authentic Rock in 1985 was to A) buy the corporate-sponsored repackaging of the 1960s/1970s hippy-era Rock albums that were experiencing a renaissance spawned by the recent popularization of a new industry technology called compact discs. B) cruise the used record stores, thrift shops, estate/yard sales for original albums. Or C) seek music by college rock or underground bands (the Replacements, Sonic Youth, Husker Du, Throwing Muses, the Pixies, and R.E.M).

But this last option wasn’t easy. And it wasn’t sustainable. For one thing, the record industry was sniffing around for these underground bands and pressuring them into selling out. You might think, “What’s so terrible about selling out?” After all, since the dawn of the Beatles, millions of kids across Western civilization had formed Rock bands with the dream of fame and fortune. But by the mid to late 1970s that dream had been corrupted by corporate forces and an alternative dream emerged. It was the underground Rock band dream, a dream that preferred a record store-geek kinda fame — the kinda fame where the critics and music junkies cherished your brilliant records, while mainstream boobs barely knew any of your songs. It was a Big Star fame, a Modern Lovers fame, a MinuteMen fame, a Velvet Underground fame, a Joy Division fame, a Pere Ubu fame, a fame that the Replacements were toying with… and if R.E.M. would have never recorded another album after Fables of the Reconstruction, it would have been an R.E.M. fame as well.

So why isn’t one of these bands that came before R.E.M. considered to have the first modern Indie Rock album? The answer is the timing. Because of the environment that the corporate record industry had created by that time (which included finagling underground bands into selling out), 1985 is about as far back as you can go if you want to talk about modern Indie Rock. By Revolution Summer (1985), American underground bands had created a loose network that was made up of their own venues for music, their own zines, their own flyers, their own independent labels, their own college radio shows, etc. This network started completely outside of, and at odds with, the corporate record industry influence. And since the goal of any corporate industry is total corporatization — especially in 1985 — this small underground niche was something that the American corporate record industry figured they should exploit and control. Corporations basically controlled every aspect of Rock music. Corporations controlled the record companies, they controlled booking agencies, the music venues, the radio stations. They controlled distribution, publishing, the merchandising — anything related to making money from Rock music was under the corporate influence. And the corporations controlled marketing, which (*activate Dewy Finn voice) included a little things called Mtv… and Rolling Stone magazine… and the soon-to-be Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, etc. All of which meant that making a living from a small independent label was simply not viable by 1985.

So was REM actually even an Indie band? Were they the rare exception that was immune to corporate control? Or were they just another pop band on the corporate assembly line?

For the making of Fables, the answer is “Yes, they were an indie band.” Which probably requires some explaining. In 1981 R.E.M. released its first single “Radio Free Europe” on the local independent label Hib-Tone. Hib-Tone could not keep up with the demand for the single and, after turning down major label RCA Records, R.E.M. signed with IRS Records (which was distributed under Herb Albert’s brainchild A&M Records at the time) in 1983. R.E.M had an “in” with I.R.S. via Ian Copeland who ran a booking agency in Macon, Georgia where R.E.M drummer Bill Berry worked. Ian’s brother Miles was I.R.S’s founder. I.R.S. had success after signing the band that the other Copeland brother, Stewart, played drums for — that being the post-punk poster boys the Police. Despite I.R.S’s success with the Police (and the Go-Gos) — it was an independent label, not much different from the Indie labels of the 1990s. They certainly were not in the same league as the major record label companies, and they certainly were artist-friendly and had a genuinely hand-to-hand working relationship with their bands. The problem was that shortly before R.E.M began recording Fables of the Reconstruction, I.R.S. changed from A&M Records to MCA, and MCA made it known that they were not happy with the lack of commercial success of R.E.M’s first two albums. This led to a contentious relationship between MCA and R.E.M. with I.R.S. in the middle. Which brings us to late winter, February 1985, as pressure from MCA was escalating, R.E.M. found themselves at a crossroads, looking out in all directions at this unsettling, murky, and menacing music industry landscape. Stipe, Buck, Mills, and Berry were very much a band that believed in their unique artistic vision. They were still young men who had not yet sold their souls. So against I.R.S’s wishes, R.E.M. flew off to London with Joe Boyd and decided to pursue their creative vision. And it just so happened that because of the timing and the circumstances involved, this put them in position to create the first Indie Rock album of the modern era. But, this is only part of the reason that Fables is the first modern Indie Rock album.

If Fables had been like R.E.M’s first three releases (Chronic Town EP, Murmur, or Reckoning) it would have been just another collection of very good to great songs. R.E.M. could have done that very easily, but they were evolving, both musically and lyrically (thematically). Fables didn’t just string a bunch of great songs together, it introduced a new aesthetic — an aesthetic that rose straight from R.E.M’s artistic vision and innovative sonic qualities. And it was the aesthetic that would have a huge influence on every other Indie Rock album to follow. Up to this point in Rock history there hadn’t really been an album that sounded like Fables. Fables was so unique and foreign to fans and critics’ ears, that people simply did not know how to describe it. By default, folks categorized it as a concept album. The case for categorizing Fables as a concept album is obvious. Fables has continuity in its theme and continuity in its sound and the way these two things meld together causes you to listen to the album on a holistic basis. It requires you to enter a listening experience that creates a totally different mind-space in a very unique way.

First of all, the unique sonic vibe weaved throughout Fables is very recognizable in the deep murky, gooey sound that Joe Boyd was able to pull from deep within the grooves and synergy that was created in the interplay that flowed from Berry, Buck, Mills and Stipes as they journeyed into deep, rich communal musical pockets during the recording sessions of Fables. If you’ve ever been in a band, maybe you have experienced this magic before. It’s like telepathy. It involves chemistry, it involves existing in a vibe, it involves time and space and completely zoning out of everything else and just digging the transcendental moment of the music. There’s an undeniable, extra-sensory cosmic level that some bands meld into. R.E.M had reached that level before, but they were more evolved now, more mature, tighter. Boyd was able to capture that alchemy from deep inside the DNA of the grooves and the riffs that R.E.M. had tapped into. Distinct to R.E.M’s magical goo was their counter-intuitive instinct of turning their sound down. The lead vocals on Fables were somewhat back in the mix (especially compared to most recorded music of that era). The same goes for Buck’s guitars and Berry’s drums. By putting all the instrumentation (including the bass) on an equal level, it made input by all contributors equal, and it allowed R.E.M. to play together and to play off each other. It made it to more easily attain that musical pocket where that cosmic goo exists — that cosmic goo that served as a foundational locomotive force for the album.

— -

A quick tangent about capturing and recording that cosmic goo, and why Fables sounds very different from everything else that was going on in the world of recorded music at that time. 1985 was an era of music production where capturing the magical goo that bleeds riffs and grooves together was not the focus. The focus of producers was on getting everything to sound clean and shiny and surgically separated. Sanitized. Sterile. And the reason for this trend toward clean separation was largely due to innovations in digital recording equipment and techniques and the fact that the corporate recording industry had stock in all of this new equipment and technology. The major record labels were pushing this trend with Warners Brothers Inc (the label that R.E.M would eventually sign to in 1988) barking the loudest from atop the digital-trend bandwagon. Warner Brothers had released the first ever digitally-recorded pop record in the United States back with Ry Cooder’s 1979 album Bop Till You Drop — ironically, mostly a collection of cover songs from the 1950s. Warner Brothers also had just scored the first digitally-recorded album to ever hit Number 1 in the Billboard Top 200 with Madonna’s Like a Virgin — a huge, blockbuster album that had been released just a couple months before R.E.M’s Fables sessions. Warner Brothers was also releasing Dire Strait’s Brothers In Arms album (that was released just a couple weeks before Fables — May 13, 1985) which became the biggest-selling digitally-recorded album of the 1980s and the first record to ever have more CD sales than actual vinyl albums sold.

— -

With the record-producing industry trending toward digital, the pressure to record digitally was growing intensely and MCA was pushing I.R.S to use a producer on R.E.M’s next album who was on the digital bandwagon. The Freewheelin’ Joe Boyd was not that producer. Joe Boyd believed in the magical musical goo and communal vibe that was unique to folk rock, and after hearing R.E.M’s 14-song demo recorded at Jim Hawkings’ studio, he realized he had an opportunity to capture the sounds of a band that was truly able to tap into that magical, musical time-space continuum. He knew the approach to take for the album, and he knew that in order to steer clear of corporate interference, he would have to sneak R.E.M. off to his studio in dreary wintertime London and create this album. As it ended up, in order to sneak off and record it, Berry, Buck, Mills and Stipes had to go behind the backs of the corporate hacks. They ended up paying Boyd out of their own pocket (as opposed to taking money from IRS as was customary) thereby setting the precedent for Indie Rock albums to come.

Creating the modern Indie Rock aesthetic.

How do you go about creating a masterpiece? Joe Boyd regarded at least seven of the songs from the Jim Hawkings’ demo as ‘very good’ to ‘great’ even in their raw form. Of the rest, there was some potential, but they would need some work. Also, he was aware of a few other tracks floating around the R.E.M. stratosphere. Several songs that ended up on the IRS compilation album Dead Letter Office (released in April of 1987) were available to Boyd. This included “Ages of You”, “Burning Hell,” and “Burning Down”. There were also a couple of songs (“Hyena” and “Windout”) that were recorded during a trip to the UK on November 21, 1984, at Rock City nightclub in Nottingham that Boyd could consider, but first, there was one song from the Hawkings’ demo that, although not exactly a very good or great song, had captured Boyd’s attention. It was “Wendell Gee”. Peter Buck flat-out didn’t like the song. It was mainly written and performed by Mike Mills, who was the secondary vocalist and bass player for R.E.M. In most bands, a bass player/backup singer would not have much say in… well, in anything. In fact, they would have to expend a healthy amount of energy and frustration in trying to get his/her contributions into any song. But R.E.M prided itself on its socialistic approach to the band. All members received equal songwriting credit, all members got equal say. So, while going through their material at Livingston Studio, Boyd brought up “Wendell Gee” and asked the band to give it a go. Buck dutifully participated, but his lack of enthusiasm for the song was obvious. Even listening to the demo version they recorded at Jim Hawkins Studio, it seemed like he was just going through the motions on his guitar part. Boyd was experienced and perceptive enough to instinctively understand band dynamics and he came up with a brilliant move.

Boyd had an infinity for obscure folk instruments, as witnessed by the cover of the Incredible String Band’s first album, which displays the band members in Boyd’s London office circa 1966, surrounded by every kind of old, weird American instrument you could imagine (from kazoos and tin whistles to mandolins and fiddles). Noticing Peter Buck’s passive semi-participation in the session for “Wendell Gee”, Boyd reached for a banjo he had on hand and gave it to Buck. Within minutes, Buck was engulfed with the unfamiliar instrument and was putting together the banjo part that would be introduced about halfway through “Wendell Gee”. This banjo part ended up providing the exact energy and strange little moment the song needed, giving it a lift right into the soaring counterpoint harmonies between Mills and Stipes as they were waltzing their way into a build-up that leads to the song’s poignant, heart worn conclusion. Additionally, underneath it all, Boyd introduced another old, weird American staple, the violin. Barely audible at first, this melancholic violin part subtly crested over and receded under the harmonies and instrumentation like a small hypnotic wave. The dance between the violin and Stipes/Mills’ vocals waltzes until the vocals reach for their final gasp, as it gives way to the violins creaking halt like a model-T with worn brakes, thus providing the final tortured moment of the song (and album). And giving Fables its perfect ending.

Fables is filled with brilliant jarring sonic moments like the ending of “Wendell Gee” that pierce through the conscious hum of the listening experience. And it is filled with moments like Buck’s banjo part — moments that cause momentum changes out of nowhere, moments that create a unique pulse that give a sensation similar to that of traveling (traveling by train especially). These moments would shape and punctuate the feel and theme of Fables throughout the entire listening experience. Moments where the drums seem to be lagging behind a half beat, trying to catch up with the melody or the guitars, only to actually overrun them and force them to catch up. There are other moments when the instruments halt, and all goes quiet save for a lone vocal by Stipes or a haunting guitar riff by Buck, only to start again and carry the momentum on even further, with new energy, deeper into the crux of the song’s vibe. These sonic moments create the kinds of interruptions, uncertainty and curiosity of what is to come next — the sensations associated with travel, and the unique enlightenment that one experiences during travel. And all these little delays and push forwards are totally grounded in that deep, thick murky goo that R.E.M inhabits and that serves as the locomotive for Fables.

Forming the perfect threesome with R.E.M’s musical goo and Boyd’s production is Stipe’s lyrics which galvanize the sonic vibe into the emotive themes that take the entire listening experience to another level that is central to the modern Indie Rock aesthetic. The first clue that there’s something strange going on in the literature of Fables, is actually in the title itself. Or the two titles: Fable of the Reconstruction and Reconstruction of the Fables. The band refused to decide on which of these titles to use, so they used both (the record label chose Fables of the Reconstruction — although both titles are on the album). So the listener is left wandering, well which one is it? Is this album about fables of Reconstruction? Or is it about reconstructing Fables? Then, if the title wasn’t enough of a hint that, your perceptions are going to be challenged, Stipes warns us on “Feeling Gravitys Pull”, the very first song on the album, by singing “Time and distance are out of place here.” This lyric could have been another one of Stipes’ impressionistic lines like those on R.E.M’s previous albums, but instead, this time, Stipes uses the lyric to set a theme that is at the very core of Fables’. By declaring that time and space are out of place here in “Feeling Gravity’s Pull,” Stipes is announcing that a change is being made — which is basically the definition of what the word “Reconstruction” means. A changing from the old ways, a changing of minds. In this light, the title could be a metaphor for the changes going on in Stipes’ mind, or R.E.M’s consciousness in general, the transitions they are making in their career, or even the changes happening in the recording industry in general.

But these lyrics denote a larger context as well. Stipes, a student of history, was an army brat who traveled a lot as a kid, and he traveled a lot with R.E.M. He was piecing together lyrics in notebooks in the weeks leading up to the recording sessions for Fables, often seen scribbling things down while traveling. Certainly, these lyrics could be part of the process of him figuring out his own mind, but what we see running through Fables is that Stipes has conformed his thoughts and emotions from these notebooks into the lyrics that form a narrative that runs throughout Fables. This narrative approach to his lyrics represented a huge departure from his previous approach to lyrics. Stipes explained that prior to Fables: “I felt I had gone as far as I could with stream-of-consciousness writing, and I needed to write about something real or something narrative.”

The result was that Stipes’ lyrics created a narrative that explored literary themes and motifs that basically revolved around travel, trains, rural spaces/small towns, local outsiders, southern dialect, etc. One of the strengths of the lyrics is that Stipes feasts on quirky details that seem as though they have been pulled from real-life yet impressionistic travel stories that specifically chronicle the rarely seen, outsider settings and happenings of rural, South United States. As reviewer Matthew Perpetua described, the songs are “preoccupied with the behavior of mysterious older men” as they imagine “the inner lives of outsiders and recluses.” The details, as well as the dialectic phrasings that Stipes include, work in a strange way with the sonic goo that is going on. They do so in a way that Perptua described as evoking “images of railroads, small towns, eccentric locals… and a vague sense of time slowing to a crawl.”

The manner in which Stipes organizes and delivers these lyrics creates the telling of a journey. A journey that begins with the falling-into-a-dream abrasive tug of “Feeling Gravitys Pull” and ends with the melancholy wake-up of “Wendell Gee” — a song that was based on a dream, but whose central character is the sad personification of the South and Southern ways. Stipes, as narrator, as an all-seeing travel guide and carny barker, takes his fellow travelers on this dream-like tour to obscure, not-often-seen rural places of the southern United States: a journey over the terrain that Rock critic Greil Marcus referred to as the Old, Weird America. Be prepared to expand your perspective and even possibly switch your total consciousness, Stipes seems to warn.

How Stipes achieves this task as tour guide, is that he deploys a couple of inventive literary techniques which firmly place the listener into the mind space of the Southern United States. One technique he uses is to reference real-life people, real-life places and real-life situations. In “Driver 8” Stipes references the railway (the Southern Crescent) as he sings of a train conductor that has conversations with the front wheels of his locomotive. In “Life and How to Live It” Stipes introduces us to Georgia native and Independent writer Brivs Mekis. who built “two doors to go between the wall” of his house (Mekis had two different styled houses built within the same house so that he could switch to a separate home whenever his mood changed). In “Old Man Kensey” Stipes sings of a local prankster who kidnaps dogs. In “Maps and Legends” he sings of outsider artist and Baptist preacher Howard Finster who paints maps that don’t seem real. Stipes references a real life place (Philomath) in “Can’t Get Here From There” and he references a real life comet in “Kohoutek”. The result of having so many real life people and places is that the lyrics conjure the massive, foreboding, ominous reality of the South. To expand on that, Stipes punctuates his descriptions of southern characters and places and situations with dialect that is representative of outsider Southern U.S. culture. In “Good Advices” he says things like “when you greet a stranger, look at his shoes”. The title phrase of “Cant get there from here” is another sharp example, as is “selling truth on the Go Tell crusade” phrase from “Driver 8”. Stipes lyrics and phrases uniquely conjure the invisible, dark ominous, cloud that the U.S. Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction cast over the South for the previous century. As Stipes guides us on this dream-like journey, there is no escaping this dark cloud — it is an undercurrent in the gestures and words of the odd assortment of characters and outsider personalities, and we see it in the abstract manner in which they have eaked out an existence and created their own way life under this long dark shadow.

Howard Finster

Howard FinsterIn the end, after listening to Fables you feel like you have been on a journey. The way R.E.M was able to yoke a sonic atmosphere and lyrical themes into a cohesive, emotive piece created an aesthetic that became the blueprint for countless other Indie Rock bands to follow over the next four decades (think Modest Mouse’s The Lonesome Crowded West, Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeoplane over the Sea, Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs, etc). At a time when corporations had nearly completely taken over Rock music and covered it in a plastic digital sheen, Fables became a light in the darkness. A spark that provided the example of what Indie Rock could be and should be. It is the proof that albums can be much more than just a collection of songs to dance to. It shows that albums can be holistic artistic explorations into emotions, thoughts, memories, values. This aesthetic that Fables presented, right during the ugly, dark era of corporate rocks take over, lives on today and still exists in the best examples of Indie Rock albums of the 21st century.

* Part of R.E.M’s loyalty to analog recording can be traced back to Jim Hawkings’ Studio in Athens. That studio was actually the fulfillment of a dream that soul man Otis Redding shared with his good friend and backing musician Jim Hawkins shortly before Redding lost his life in a plane crash. It took Hawkings more than a decade to fulfill this dream of creating the kind of studio that he and Otis dreamed of, but when he did, R.E.M. was the first band to record there. It was still their go-to studio when they laid down the 14 tracks destined for Fables.

[image error]who will save rock n roll?

- Ed Wagemann's profile

- 67 followers