Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, Final Thoughts

“Melko shalt see that no theme can be played save it come in the end of Ilúvatar’s self, nor can any alter the music in Ilúvatar’s despite. He that attempts this finds himself in the end but aiding me in devising a thing of still greater grandeur and more complex wonder:–for lo! through Melko have terror as fire, and sorrow like dark waters, wrath like thunder, and evil as far from the light as the depths of the uttermost of the dark places, come into the design that I laid before you. Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and Death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorrow, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilúvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we recap The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, and in doing so, speak about the more fantastic aspect of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s intention.

The Book of Lost Tales is an amalgam of Tolkien’s work throughout his life. Christopher has included some of his father’s earliest poems, scraps of notes stuck into notebooks, various illustrations, and books and books of re-writes to show the thought and care Tolkien put into the work.

John wanted to tell a fantastic story that would give people meaning. He wanted a new fairy tale that would anchor into our world and give people wonder and hope (and perhaps even give reasoning for things like The Great War).

Many critics have said that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory to Tolkien’s time in the war, and if you only read the book itself, it is easy to understand why. Tolkien, however, hated allegory and had often stated that he pulled inspiration from his time in the war, but there was no allegory there. That can be hard to swallow, especially when his fellow Inkling (a society of writers who met to critique and edit each other’s work), C.S. Lewis, thought allegory one of the greatest literary techniques.

The story produced in The Lord of the Rings was a work of love developed over many decades, but to create a work so deep and well established Tolkien wanted a robust history of the world, that history is what eventually became The Silmarillion.

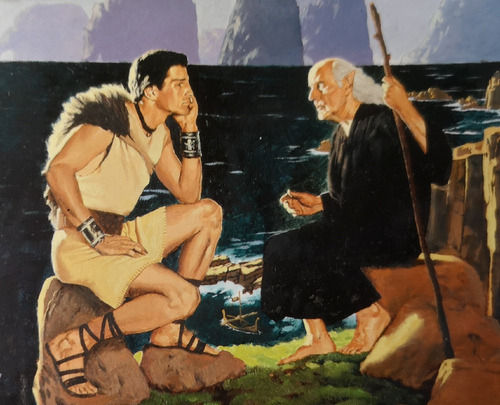

But Tolkien, like many authors, wanted the history of the world to be a story in and of itself, so in the earlier iterations, we get the tale of Eriol, who in turn is told the story behind The Silmarillion.

The problem Tolkien ran into, however, was that history is difficult to tell in a story format. There are fantasies, records, and fairy tales told in the Silmarillion, but they come late in the book and feel more like what he would eventually write in The Lord of the Rings. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, is Eriol learning instead about the Valar and how the Eldar (Gnomes in this earlier version) came into being. However, even in these earlier versions, we still need to catch minor differences with how Tolkien later decided to frame everything.

Facts, like the Maiar being the children of the Valar, the Eldar being Gnomes, and the sparse inclusion of Fëanor are stark differences to how the story eventually played out, and what is great about reading through this book was being able to read Christopher’s analysis (Tolkien’s son and editor) of where Tolkien tried to take the story, and where he decided to end up. This process is the magic of reading The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Part 2, I’m sure, will have just as many quirks, but part 2 is where the stories that built the history of Mankind came into being. Stories like the Lays of Lúthien, the Tale of Túrin Turambar, and the Fall of Gondolin all take place in the second half of these histories. These tales inform our characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Beyond The Silmarillion, there is minimal mention of the Valar or Ilúvatar.

In Christopher’s sentiment, the first book is less interesting because it’s about the development of the world itself and not necessarily about the people; thus, it’s harder to give stakes because we know what will eventually happen.

Knowing all this, Ilúvatar is the most provocative being or concept in Tolkien’s oeuvre. Ilúvatar is God for this World (even though the Valar intermittently are called gods, Tolkien later stripped them of that title for The Silmarillion).

The quote to start this essay is a perfect example of the fallibility of gods in general. Tolkien was deeply religious, and I’m sure he wrote Ilúvatar to be Middle-earth’s Yahweh and much of the struggle and philosophy in Middle-earth is how to accept or deal with the concept of Death. Death is a “gift” given to Man when they are born, so they might make life more meaningful. Death was not a concept until Morgoth sang its theme into existence.

This path makes Melkor the most tragic character in the pre-history of Middle-earth because, as we see from the opening quote, he has no choice. Ilúvatar, as the master creator, knew every theme he wanted to put into the world, and Death, hate, and suffering would be part of existence.

Iluvatar created each Vala to inform specific parts of his themes, but themes were all they were, meaning that the Valar had free will over what theme they were given. Iluvatar created Melkor to suffer. He created him to be a Dark Lord because he knew that without a Dark Lord making people work for their freedom, they would take their lives for granted.

Tolkien didn’t write Allegory; he wrote philosophy. Death is a gift because we cannot appreciate light without darkness. We cannot fully appreciate life without death.

Come join me next week as we begin our foray into “The Book of Lost Tales, part 2,” the second book of the Histories of Middle-earth!