The Odd Creatures of the Sixth Day

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

What do we mean when we say we're made made in God's image?

As the church encroached upon the world beyond its immediate apostolic setting, it encountered many pagans who welcomed the new gospel that Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim lives with death behind him. By raising Jesus from the dead, the true God had answered Israel’s anthropological despair. The gospel imputed a novel dignity and revolutionary value to human creatures. Just so, the proclamation of this good news— the verification that all is not vanity— created a new community comprised in no small part by categories of people previously excluded according to the religion of Plato.

It speaks to the church’s evangelical success that what the pagan world received as revolutionary, we now take for granted. “Man is made in the image and similitude of God,” asserts an early Protestant Reformer, “which distinguishes him from all other corporeal creatures.”

The tradition has made the phrase “image of God” a comprehensive attribute for the uniqueness of human beings though the rubric plays a surprisingly minor role in the scriptures.

The image of God language, eikon in the New Testament’s Greek, appears variously in the epistles:

Romans 8.29

1 Corinthians 11.7 and 15.49

2 Corinthians 3.18

Colossians 3.10

In each instance, the word eikon is not irreplaceable; that is, the dogma about human uniqueness is not the concern of the texts where the term appears. What’s more, the Old Testament speaks only once of the imago dei:

“And God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” — Genesis 1.27

The centrality of the imago dei doctrine owes more to the church fathers’s affinity for image metaphysics of late antiquity, Robert Jenson argues, rather than to its explicit prominence in the Bible. For ancient aesthetics, “image” denoted the relationship of a work of art to its archetype. If we take the doctrine of the imago dei for granted, then we also seldom probe the question posed by this aesthetic analogy.

How do the creatures of the sixth day resemble God such that other creatures do not?What characteristics do we share— albeit analogously— with God that we do not share with other creatures such that the difference accounts for a divine resemblance? How do humans fit into time differently than the birds of the air and the beasts of the field?The tradition has ventured an answer: we are made in God’s image in that we are personal subjects as God is a personal subject. We resemble God, then, as we are rational creatures. Aquinas summarizes the tradition’s answer in his Summa,

“Such resemblance to God as can be called an image is found only in rational creatures…that in which rational creatures surpass others is intellect or mind.”

Whatever wisdom this answer possesses it is nevertheless an answer far afield from the creative address in the Book of Genesis. Another dilemma introduced by the traditional understanding of the imago, Jenson notes, is its ambiguity over whether the imago names an actuality or a potentiality. Do we resemble God by the sheer fact of subjectivity or by the qualities in which subjectivity is fulfilled?

Jenson:

“Do we resemble God by intelligence or by knowledge and wisdom? By the possession of will or by virtues? By the capacity to judge or by right judgments?”

With Aquinas, Catholic theology tends to answer with the former while the Protestant Reformers lifted up the latter. Luther believed identifying the human creature’s imago dei merely with intelligence, will, and the capacity to judge failed to distinguish the God of the gospel and it failed to account for what the human creature lost under the regime of Sin and Death.

“If it is simply these capacities that are the image of God,” Luther writes in his lectures on Genesis, “it must follow that Satan was created in the image of God.”For the Reformers, the imago dei denotes the holiness and righteousness and steadfast love that so identifies Israel’s God. The difficulty with the Protestant answer, however, is that this description in no way suits fallen humanity. And, once again, this definition of the imago dei draws a resemblance between Creator and creatures that is removed from narrative context of the only scriptural passage to make the claim of such a resemblance. The difficulties of the traditional teaching arise, Jenson argues, by failing to conceive of humanity’s specific relation to God as itself our uniqueness but instead seeking a complex of qualities, supposedly possessed by us and not by other creatures, that are claimed to resemble something in God.

Again— Definitions of the imago dei fail to attend to the passage in Genesis.

Again— Definitions of the imago dei fail to attend to the passage in Genesis.Writes Jenson:

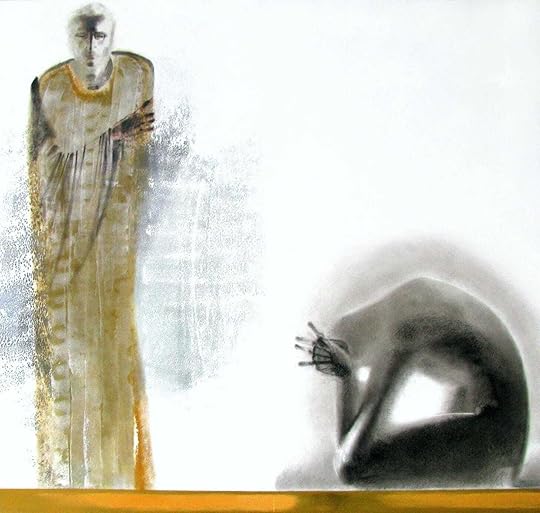

In other words, the odd creatures of the sixth day are the only creatures whom the Lord addresses.“In Genesis, the specific relation to God is as such the peculiarity attributed to humanity. If we are to seek in the human creature some feature to be called the image of God, this can only be our location in this relation. As the relation is the occurrence of a personal address, our location in it must be the fact of our reply.”

How do we fit into time differently from the other animals?

We are those animals “addressed by God’s moral word and so enabled to respond.”

We are the creatures who resemble their Creator in no other way but that we are called to pray— pray, as the liturgy puts it, “not only with our lips but by offering up our lives as a sacrifice…”

We are the only creatures who use the word “God” as a vocative. We are made in God’s image in that we are the only creatures classifiable as “praying animals.”How we do understand the imago dei of those who do not understand themselves to pray?

Jenson answers:

“To forestall the objections that will crowd the mind, it should be noted that blasphemies, deliberately stopped ears, mindless oaths, decisions to eschew prayer and so on are all in their perverse ways prayers, together with the multitudinous prayers of religions that misidentify the addressee. It should be further noted that no responding word is instantaneous with the address to which it responds; if the response of some comes only at the Last Judgment and then is “Curse you, God,” just then they are human.”

As the triune God just is a community— a conversation— of address and reply, just so prayer is the unique and solitary way we resemble Father, Son, and Spirit. That is, by the very act of giving visibility to wishes directed beyond ourselves, we nevertheless in fact give up control and worship and, in so doing, we creatures take on the likeness of the One we beseech.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers