Victoria Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

I wonder whether memoryis different for immigrants, for people who leave so much behind. Memory isn’t somethingthat blooms but something that bleeds internally, something to be stopped. Memoryhides because it isn’t useful. Not money, a car, a diploma, a job. I wonder ifmemory for you was a color.

When we say thatsomething takes place, we imply that memory is associated with a physicallocation, as Paul Ricoeur states. But what happens when memory’s place of origindisappears? (“Dear Mother,”)

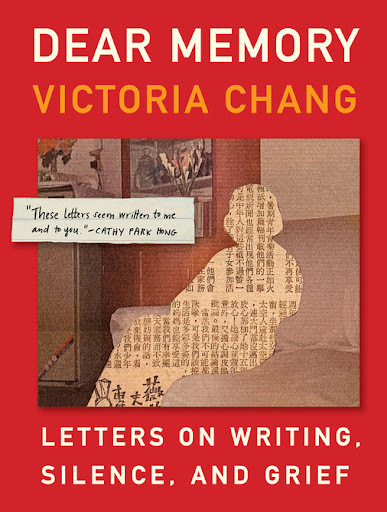

LatelyI’ve been going through Los Angeles-based poet Victoria Chang’s strikingnon-fiction project, the stunning and deeply felt, deeply intimate

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

(Minneapolis MN: MilkweedEditions, 2021), a book of memory, history and mentors. Interspersed with collagedarchival photographs and other documents, the collection is composed as asequence of letters individually directed to intimates such as her lateparents, childhood friends, acquaintances and former teachers, as well as to herdaughter. Dear Memory follows Chang’s poetry collections Circle (SouthernIllinois University Press, 2005),

Salvinia Molesta

(University of GeorgiaPress, 2008),

The Boss

(McSweeney’s, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Barbie Chang

(Copper Canyon, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Obit

(Copper Canyon, 2020) [see my Griffin Prize-shortlist interview with her here],although I’m realizing how far behind I am on her work, having missed

TheTrees Witness Everything

(Copper Canyon, 2022), with a further poetrycollection forthcoming in 2024 with Farrar, Straus & Giroux: With MyBack to the World.

LatelyI’ve been going through Los Angeles-based poet Victoria Chang’s strikingnon-fiction project, the stunning and deeply felt, deeply intimate

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief

(Minneapolis MN: MilkweedEditions, 2021), a book of memory, history and mentors. Interspersed with collagedarchival photographs and other documents, the collection is composed as asequence of letters individually directed to intimates such as her lateparents, childhood friends, acquaintances and former teachers, as well as to herdaughter. Dear Memory follows Chang’s poetry collections Circle (SouthernIllinois University Press, 2005),

Salvinia Molesta

(University of GeorgiaPress, 2008),

The Boss

(McSweeney’s, 2013) [see my review of such here],

Barbie Chang

(Copper Canyon, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Obit

(Copper Canyon, 2020) [see my Griffin Prize-shortlist interview with her here],although I’m realizing how far behind I am on her work, having missed

TheTrees Witness Everything

(Copper Canyon, 2022), with a further poetrycollection forthcoming in 2024 with Farrar, Straus & Giroux: With MyBack to the World.Thisis a book of contemplation, recollection and reconciliation, as Chang offers thefluidity of a combined book-length essay and memoir through the form of journaledand unsent letters. There is such an intimacy and an openness to the way sheholds the book’s form, one that predates, arguably, even the novel; think of bookssuch as The Pillow Book (1002) by Sei Shōnagon, or even Bram Stoker’soriginal Dracula (1897). The back-and-forth of recollection in Chang’s DearMemory are even reminiscent to what Kristjana Gunnars wrote about in hernovella, The Prowler (Red Deer College Press, 1989): “That the past resemblesa deck of cards. Certain scenes are given. They are not scenes the remembererchooses, but simply a deck that is given. The cards are shuffled whenever agame is played.” Or, as Chang writes, mid-point through the collection: “Now I admirewriters who write with an intimate intensity but also a generous capaciousness.I enjoy reading work that expands while it contracts. Writing made by aninstrument with a microscope on one end and a telescope on the other, leavingsome powder on the page in the form of language.”

Dear Memory writes to and around her immigrant parents,offering her childhood as a foundation for the collection the narrative spreadsinto, through and beyond, including her own ways through thinking and intopoetry. Chang writes of memory as a way to articulate becoming, and anarticulation around writing, around poetry, is as foundational to her as the lostthreads of either of parent’s lives, the sequence of multiple familyrestaurants they ran and the difficulty of being the only child of Asian descentin predominantly white communities. There is such an intimacy to these pieces,one that demands slowness, demands attention. One that is framed around an acknowledgmentof loss, both long past and those losses that are ongoing, but composed in amanner through which to solidify, before those losses slip entirely away. “Memoryis everything,” she writes early on, in a lettet to her mother, “yet it isnothing. Memory is mine, but it is also clinging to the memory of others. Some ofthese others are dead. Or unable to speak, like Father.” Or, as the piece “DearTeacher,” begins:

I stumbled into yourpoetry workshop even though I wasn’t studying poetry. I was one of the fewgraduate students there. I remember you at the head of a long wooden table,presiding, as if your chair were a throne. The room was brown with woodeverywhere. We were knights of poetry. our plates were white sheets of paperfilled with our own flesh. Your words were infinite. They were an entirecountry.

At the end of class, youwrote each student a note. Your note said my poetry had become poems out ofpoetry and that my poems had begun to strike forward to the possibility…You also wrote that you wished I had made my voice more present in class andthat my form of articulation was far from shy. You told me to call totalk about next semester.