How the Devious Fossil Fuel Industry Cooked Up the Carbon Footprint Sham

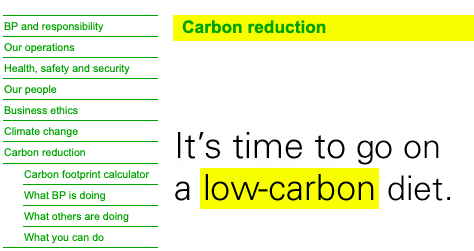

Screenshot of BP webpage as documented by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine on Feb. 12, 2006

Screenshot of BP webpage as documented by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine on Feb. 12, 2006

A ‘successful, deceptive’ PR campaign

Moving forward requires focus. Mashable’s Social Good Series is dedicated to exploring pathways to a greater good by spotlighting issues that are essential to making the world a better place.

In a dark TV ad aired in 1971, a jerk tosses a bag of trash from a moving car. The garbage spills onto the moccasins of a buckskin-clad Native American, played by Italian American actor Espera Oscar de Corti. He sheds a tear on camera, because his world has been defiled, uglied, and corrupted by trash. The poignant ad, which won awards for excellence in advertising, promotes the catchline “People Start Pollution. People can stop it.” What’s lesser known is the nonprofit group Keep America Beautiful, funded by the very beverage and packaging juggernauts pumping out billions of plastic bottles each year (the likes of The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, and Anheuser-Busch Companies), created the PSA.The real message, underlying the staged tear and feather headdress, is that pollution is your problem, not the fault of the industry mass-producing cheap bottles.

Another heralded environmental advertising campaign, launched three decades later in 2000, also won a laudatory advertising award, a “Gold Effie.” The campaign impressed upon the American public that a different type of pollution, heat-trapping carbon pollution, is also your problem, not the problem of companies drilling deep into the Earth for, and then selling, carbonaceous fuels refined from ancient, decomposed creatures.British Petroleum, the second largest non-state owned oil company in the world, with 18,700 gas and service stations worldwide, hired the public relations professionals Ogilvy & Mather to promote the slant that climate change is not the fault of an oil giant, but that of individuals.

It’s here that British Petroleum, or BP, first promoted and soon successfully popularized the term “carbon footprint” in the early aughts. The company unveiled its “carbon footprint calculator” in 2004 so one could assess how their normal daily life — going to work, buying food, and (gasp) traveling — is largely responsible for heating the globe. A decade and a half later, “carbon footprint” is everywhere. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a carbon calculator. The New York Times has a guide on “How to Reduce Your Carbon Footprint.” Mashable published a story in 2019 entitled “How to shrink your carbon footprint when you travel.” Outdoorsy brands love the term.

“This is one of the most successful, deceptive PR campaigns maybe ever,” said Benjamin Franta, who researches law and history of science as a J.D.-Ph.D. student at Stanford Law School.do matter.) But there’s now powerful, plain evidence that the term “carbon footprint” was always a sham, and should be considered in a new light — not the way a giant oil conglomerate, who just a decade ago leaked hundreds of millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, wants to frame your climate impact.

The evidence, unfortunately, comes in the form of the worst pandemic to hit humanity in a century. We were confined. We were quarantined, and in many places still are. Forced by an insidious parasite, many of us dramatically slashed our individual carbon footprints by not driving to work and flying on planes. Yet, critically, the true number global warming cares about — the amount of heat-trapping carbon dioxide saturating the atmosphere — won’t be impacted much by an unprecedented drop in carbon emissions in 2020 (a drop the International Energy Agency estimates at nearly eight percent compared to 2019).

This means bounties of carbon from civilization’s cars, power plants, and industries will still be added (like a bank deposit) to a swelling atmospheric bank account of carbon dioxide. But 2020’s deposit will just be slightly less than last year’s. In fact, the levels of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere peaked at an all-time high in May — because we’re still making big carbon deposits.

So when BP tweets an ad encouraging you to “Find out your #carbonfootprint” with their “new calculator,” it’s time to rethink the use of the term. While superficially innocuous, “carbon footprint” is intended to manipulate your thinking about one of the greatest environmental threats of our time. (The threat of nuclear warfare with the potential for both the harrowing spread of radioactive material and the development of a nuclear winter are in the running, too.)

[…]

“It’s time to go on a low-carbon diet,” BP wrote in bold letters on its website in 2006, with its “carbon footprint calculator” just a click away. (In 2004 alone, 278,000 people calculated their footprints.) The site was part of BP’s ad campaign, “Beyond Petroleum.”

Fast forward, and BP is still producing bounties of oil and gas every day (4 million barrels a day in 2005 versus 3.8 million barrels today). In 2019, BP purchased its “biggest acquisition in 20 years,” new oil and gas reserves in West Texas that gave the oil giant “a strong position in one of the world’s hottest oil patches,” according to the company. Today, BP touts its foray into lower-carbon fuels, but these are limited in scope. In 2018, BP invested 2.3 percent of its budget on renewable energies. Its bread and butter is still black oil and gas. What low-carbon diet?

It’s evident that BP didn’t expect to slash its carbon footprint. But the company certainly wanted the public — who commuted to work in gas-powered cars and stored their groceries in refrigerators largely powered by coal and gas generated electricity — to attempt, futilely, to significantly shrink their carbon footprint. In 14-year-old web pages no longer accessible online but documented by Julie Doyle, a professor of media and communication at the University of Brighton, BP published ads asking “What on earth is a carbon footprint?”, “Reducing our footprint. Here’s where we stand,” and “What size is your carbon footprint?”

Doyle concludes BP sought to explain what a carbon footprint is “in a way which assigns responsibility for climate impact to the individual, while BP registers its own concerns by appearing already to be doing something about it.”

Yet in a society largely powered by fossil fuels, even someone without a car, home, or job will still carry a sizable carbon footprint. A few years after BP began promoting the “carbon footprint,” MIT researchers calculated the carbon emissions for “a homeless person who ate in soup kitchens and slept in homeless shelters” in the U.S. That destitute individual will still indirectly emit some 8.5 tons of carbon dioxide each year.

“Even a homeless person living in a fossil fuel powered society has an unsustainably high carbon footprint,” said Stanford’s Franta. “As long as fossil fuels are the basis for the energy system, you could never have a sustainable carbon footprint. You simply can’t do it.”

[…]

BP, powerful and wealthy, signaled it would wean itself from oil. “Only they didn’t go beyond petroleum,” wrote Kenney. “They are petroleum.”

[…]

While the pandemic has laid bare that our personal actions alone won’t stabilize the planet’s disrupted climate, some voluntary decisions beyond voting can still be important, and influential. Here’s a poignant example: When someone installs solar panels on their roof, their neighbors are more likely to install the panels too, a trend that’s shown in multiple studies. “It’s the effect of social contagion,” said Hassol.

[…]

It’s true that each time we fill up at the pump and drive off we’re inevitably emitting heat-trapping carbon into the atmosphere. That’s technically a “carbon footprint.” But we’re given no other choice. “The strategy is to put as much blame on the consumer as possible, knowing the consumer is not in a good place to control the situation,” said Franta. “It basically ensures that nothing changes.”

[…]

BP wants you to accept responsibility for the globally disrupted climate. Just like beverage industrialists wanted people to feel bad about the amassing pollution created by their plastics and cans, or more sinisterly, tobacco companies blamed smokers for becoming addicted to addictive carcinogenic products. We’ve seen this manipulative playbook before, and BP played it well.

[…]Via https://archive.is/2022.03.27-193901/https://mashable.com/feature/carbon-footprint-pr-campaign-sham#selection-725.0-1433.70The Most Revolutionary Act

- Stuart Jeanne Bramhall's profile

- 11 followers