John Ashbery | De schilder

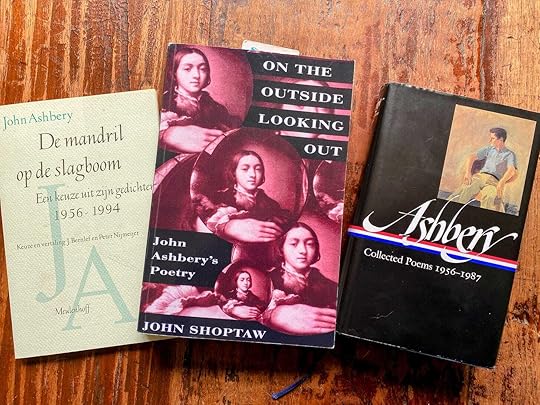

In 1995 verscheen bij Meulenhoff De mandril op de slagboom, een keuze uit de gedichten van John Ashbery, vertaald door J. Bernlef en Peter Nijmeijer. De bundel opent met een sestina, ‘De schilder’, die onder de titel ‘The Painter’ werd opgenomen in Ashbery’s officiële debuut, Some Trees (1956). Maar Ashbery schreef het al in juni 1948, op 20-jarige leeftijd.

John Shoptaw besteedt in zijn studie over Ashbery’s werk, On the Outside Looking Out, die in 1994 werd uitgegeven door Harvard University Press, afzonderlijk aandacht aan dit gedicht.

Hieronder volgt eerst de vertaling van Bernlef en Nijmeijer, daarna krijgt Shoptaw het woord, en tot slot wordt de oorspronkelijke versie van het gedicht weergegeven.

DE SCHILDERZittend tussen de zee en de gebouwenGenoot hij van het schilderen van een zeeportret.Maar net als kinderen, die denken dat een gebedSlechts stilte is, zo verwachtte hij zijn onderwerpHet zand op te zien stormen en, grijpend naar een kwast,Zijn eigen portret te kwakken op het doek.Dus kwam er nooit een spat verf op zijn doekTotdat de bewoners van de gebouwenHem presten: ‘Probeer eens de kwastTe gebruiken als middel. Kies, voor een portret,Iets dat minder onstuimig en groot is, meer het onderwerpVan wisselende stemmingen of, wellicht, van een gebed.’Hoe kon hij hun uitleggen dat zijn gebedJuist inhield dat niet de kunst maar de natuur zijn doekzou usurperen? Hij koos zijn vrouw tot nieuw onderwerp,En hij schilderde haar gigantisch, als vervallen gebouwen,Alsof, zichzelf vergeten, het portretZich had uitgedrukt zonder tussenkomst van een kwast.Licht aangemoedigd, doopte hij zijn kwastIn de zee en mompelde een oprecht gebed:‘O, mijn ziel, als ik aan dit nieuw portretBegin, laat jij het dan stranden, mijn doek.’Het nieuws verspreidde zich als een lopend vuur door de gebouwen:Hij was teruggekeerd naar de zee als onderwerp.Stel je een schilder voor, gemarteld door zijn onderwerp!Te uitgeput om zelfs maar even zijn kwastOp te tillen, kreeg hij van een paar uit de gebouwenHangende schilders hoon over zich uitgestort: ‘Geen gebedHelpt nu nog onszelf aan te brengen op dit doek,Noch de zee te laten poseren voor een portret!’Anderen bestempelden het als een zelfportret.Ten slotte begon alles wat wees op een onderwerpTe verbleken en liet het doekSpierwit. Neer legde hij toen de kwast.Meteen klonk een gejoel op, dat tegelijk een gebedWas, uit de overvolle gebouwen.Ze wierpen hem van het hoogste gebouw, met zijn portret;En de zee verslond het doek en de kwastAlsof zijn onderwerp besloten had te blijven wat het was: een gebed. *‘Another elliptical self-portrait, “The Painter,” takes up the poetics of formal perfection. Dated June 17, 1948, five months earlier than “Some Trees,” this sestina is the earliest poem collected in the volume. As in “Some Trees,” the poem’s enjambed tetrameters keep to an effortless syntax and a colorless vocabulary (the end-words are “buildings,” “portrait,” “prayer,” “subject,” “brush,” and “canvas”). It is remarkable, for instance, that the only color word in “The Painter” is “white.” The poem has little of the antic quality of Ashbery’s later sestinas (“A Pastoral,” “Faust”), which capitalize on the surrealist potential of their repeated end-words. Critics have traced the blandness of the diction to the influence of Stevens and Elizabeth Bishop. As Ashbery remarks, he “read, reread, studied and absorbed” Bishop’s North and South (1946), the volume containing het Stevensian sestina, “A Miracle for Breakfast,” before writing his own.

‘The most productive flaw in the poem is the incongruity between its formal perfection and its romantic subject matter: the painter in sublime confrontation with the ocean. Like Prufrock, Ashbery’s painter does not think the sea will sit for him. One key model for “The Painter” is Robert Browning’s “Andrea del Sarto (called ‘The Faultless Painter’).” With its source material in Vasari, its long verse paragraphs and extended apostrophe, and especially its exploration of the aesthetics and psychology of perfection, Browning’s poem will also be an important model for Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait,” for which “The Painter” becomes a preliminary sketch. Like Ashbery’s “Perfectly white” sestina, the painting by Browning’s del Sarto is monochromatic and finished: “All is silver-gray / Placid and perfect with my art.” Painstakingly painting his wife, Andrea settles for technical excellence while chafing at the flawed soulful paintings of his rivals Michelangelo and Raphael: “Their works drop groundward, but themselves, I know, / Reach many a time a heaven that’s shut to me.” Ashbery literalized Browning’s metaphor (“Their works drop groundward”) in his envoy by having rival painters drop the painter’s blank painting seaward: “They tossed him, the portrait, from the tallest of the buildings; / And the sea devoured the canvas and the brush / As though his subject had decided to remain a prayer”. This fall is also modeled on the end of Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts,” in which the ship’s crew in Pieter Breughel’s Icarus ‘must have seen / Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky.”

‘The most malleable of the end-words in “The Painter” is “subject,” meaning topic, self, and subjection. To paint his “self-portrait” the painter masters his ego (as he had his model wife) and dips his brush into the sea, subjecting his conscious perfections to his oceanic “soul,” in a parody of the impassioned self-expression of abstract expressionism (“Imagine a painter crucified by his subject!”). “‘My soul,’” Ashbery’s maritime painter prays, “‘when I paint this next portrait / Let it be you who wrecks the canvas.’” As though drawn on sand, the painting’s ambiguous “subject” loses its vital signs: “Finally all indications of a subject / Began to fade, leaving the canvas / Perfectly white.” Ashbery may not have “expressed himself” or captured his subjectivity in this perfectly sustained sestina, but he succeeds thereby in drawing the mock-heroic proportions of the subject’s submersion in his work.

‘Like most poems in Some Trees, “The Painter” is a narrative. In these early poems Ashbery begins what will be an extensive experimentation with narrative conventions. Such narratives are best read representatively in terms of their genres or modes of discourse rather than traditionally (for plot and character).’

– John Shoptaw, in On the Outside Looking Out: John Ashbery’s Poetry

THE PAINTERSitting between the sea and the buildingsHe enjoyed painting the sea’s portrait.But just as children imagine a prayerIs merely silence, he expected his subjectTo rush up the sand, and, seizing a brush,Plaster its own portrait on the canvas.So there was never any paint on his canvasUntil the people who lived in the buildingsPut him to work: “Try using the brushAs a means to an end. Select, for a portrait,Something less angry and large, and more subjectTo a painter’s moods, or, perhaps, to a prayer.”How could he explain to them his prayerThat nature, not art, might usurp the canvas?He chose his wife for a new subject,Making her vast, like ruined buildings,As if, forgetting itself, the portraitHad expressed itself without a brush.Slightly encouraged, he dipped his brushIn the sea, murmuring a heartfelt prayer:“My soul, when I paint this next portraitLet it be you who wrecks the canvas.”The news spread like wildfire through the buildings:He had gone back to the sea for his subject.Imagine a painter crucified by his subject!Too exhausted even to lift his brush,He provoked some artists leaning from the buildingsTo malicious mirth: “We haven’t a prayerNow, of putting ourselves on canvas,Or getting the sea to sit for a portrait!”Others declared it a self-portrait.Finally all indications of a subjectBegan to fade, leaving the canvasPerfectly white. He put down the brush.At once a howl, that was also a prayer,Arose from the overcrowded buildings.They tossed him, the portrait, from the tallest of the buildings;And the sea devoured the canvas and the brushAs though his subject had decided to remain a prayer. *– John Ashbery, Collected Poems 1956-1987