Clouds, Ice, Alphabets, Voices, Darkness, Rain, and Dark

I do not know how many times I have flown over the Atlantic, but the first time I did I looked out the porthole at the clouds floating below me in the sky, and I believe we were flying over the Arctic. Aged six at the time, I did not know that I would learn that those clouds were not ice, that the sky was not ocean, and I would learn it by the simple process of experience.

A dream dashed. We survive on the lies we tell ourselves, even if we are poisoned by the lies others tell us. Lies are merely things that do not exist, like ghosts. If ghosts sifted through the walls of our homes, we would be overcome with constant feel of waves of cold seeping through us, of the evanescence of death sweeping into us, deep through us. Yet we are lost, we are somehow damaged, by not having these fears to depend on. Or angels. Or gods. Or life everlasting. Amen.

A rain came an hour ago here in fat cold drops, yet I could not feel them to determine their cold. Yet I knew they were. They were drops of night, coming not black but white, just a little greyed out, for every drop fell through a stream of light, so every drop was filled with that light, and took on the undefined contours of it. When the night fell from the sky raining around me tonight, it fell in the form of lamplight, wet and cold and big, but bright.

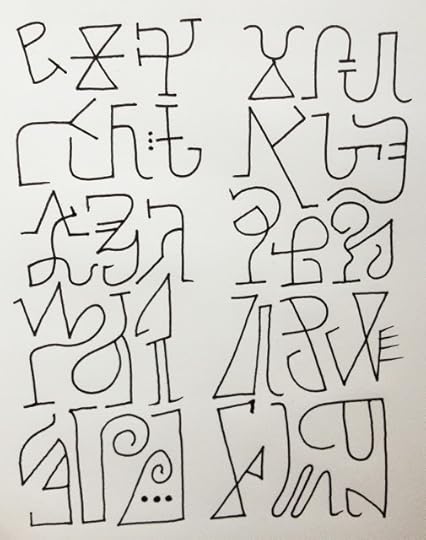

I took in my hand today a pen only recently purchased and wrote, but I did not so much write as I drew, but I did not so much draw as I wrew. And what I made were poems, only two: one made of letters that never existed, except that today made them so, but which still carried forth a message, to the future, to the present, not quite to the past. Something there was that sustained that poem, something about the shape of the letters and how they fit together and how they seemed almost of a piece, how they seemed alphabetic. (I wrote about half of this poem while riding a bus, so it preserves evidence of the means of its creation.)

If you write a message in words that no-one can read, it is unlikely they will send a search party to find you. But it is likely they will live better with the words stuffed into their eyes.

A vain claim, I realize, but one I feel compelled to make, against any hope for belief, after reading a beautiful little essay about shamans in poetry by my friend Stephen Nelson wrote recently, an essay that includes a few words about one of my instances of singing.

When my friend Geof Huth performed a poemsong at the Text Festival in Bury exactly a year ago this weekend, I thought he was a shaman. He sang into the collective energy of the room and, somehow, altered it. How this works at an atomic or subatomic level is beyond me, but I do know how it affected my body, and, more than that, how his song reached beyond my body’s physicality to a more subtle level of being where I might have found myself interacting with the memories of the room and everyone in it. His song transformed the room, altered the mind of each individual, and by extension, the families and communities those individuals belonged to.

This adjustment, this ability to heal and transform makes every poet potentially a shaman, particularly I think sound and visual poets, whose work frequently steps outside meaning into areas of pure sign, pure sound. What matters most is the loving intention he or she brings to their marks and utterances, and how that communicated intention can alter the reader/hearer’s state of being.

All of which makes nonsense of poetry wars and poetic rivalries. When a poet sings, he sings for all the poets, for a whole community of poets; similarly, when one of us suffers, we all suffer, whether we’re aware of it or not.

I wish, of course, that I had the ability to heal, that my could heal, that my singing could, my touching, my marks made onto a page, a screen, a wall, even a small corner of a ragged rugged yard. And to believe so would be to believe a rich and sustaining lie. But I cannot do it.

When I sing, I do it to affect people, to burrow into the deepest part of people without ever touching them, but I expect no effect. I just wish it. And wishes are just wants, things we are lacking. Stephen, I believe, though, felt something as I stood up that night in Bury, up out of the dark of the theater, out of the audience and up onto my feet into a bubble of light. I'm not sure why. He is a better singer than I am, a better musician, and by miles. My voice is the sound of a saw against wood then hitting a stone the trees grown around enough to hide within the cylinder of its body. I sing almost tunelessly, not of music, but as if struggling through sound to a music I cannot find. Still, these sounds are sometimes powerful to me because expel them as if spraying human and bodily feelings into the air, fat cold things that seem like pieces of night falling but which catch the light just long enough and bright enough to light the faces of the listeners, if but for a second.

I have had a long two weeks traveling back and forth across the continent in small loud planes so that I could perform before people. And these performances were not poetics. They were pedagogical. And comical. For I cannot teach in person without telling jokes, sometimes so furiously that a conversation about digital preservation formats becomes a stand-up routine. I know it is hard to believe, but it is true. At one point two days ago, the audience was laughing so continuously that I knew I had to pull back from that humor (which is almost a drug for me) so that I could keep the audience focused enough so that they can learn. Humor is important in teaching because it is a core element in my simple theory of education: You must be awake to learn. But humor gone to far disperses the mind to finely and broadly, spreads it so thin that learning slips right through it, and falls, as if darkness falling through darkness, yet light by a light from within.

So when I read Stephen's essay to me, a message from a Scotsman to a fellow Scotsman, I was filled with the cold and heavy weight of his words, words made cold because I could not believe them, words made heavy because they gave me the burden of being something I could not be (a shaman, a healer, a mover of souls). But when these words fell on me, cold and wet and slapping sharply the skin on my face, they turned to light: brightness and weightlessness. And I was held aloft by my believing in them, by my allowing myself to feel them for just long enough to heal about from the tiredness I was discarding and from the weight of work I was pulling back onto my crooked back.

It is a gift to be remembered well, even if too well. Recognition is two things: The assertion of one's value and the knowing of who one is. And it was good to be known, and even to be asserted into something I could not fit or flee.

I write, I realize, as a poet. It is a disability I cannot recover from. It is a failing I cannot shake. So I stand still for a moment, or I sit still, and I write. As I am doing now, in the rainless dark.

After my bus ride, I did not return directly to the small place where I live. I went, instead, to a neighborhood institution, for a couple of pints and an easy meal, a hot chili to warm the soul, a fine salad to soothe the body. While I was there, I soon realized I was in the midst of a meeting of the local Young Democrats and that two men running for the state assembly were vying for votes from this small body of activist liberals. The tininess of their endeavor enhanced by the greatness of their desire endeared them to me, and (after all) their politics are likely nearly mine, so I listened to their small meeting until they finished with it (even electing a new leader) and burst into their party. At which point they became not quite boisterous but engaged and happy, full humans in the enterprise of life. I do not know what lies made them so happy, but they were warm and long-lasting ones.

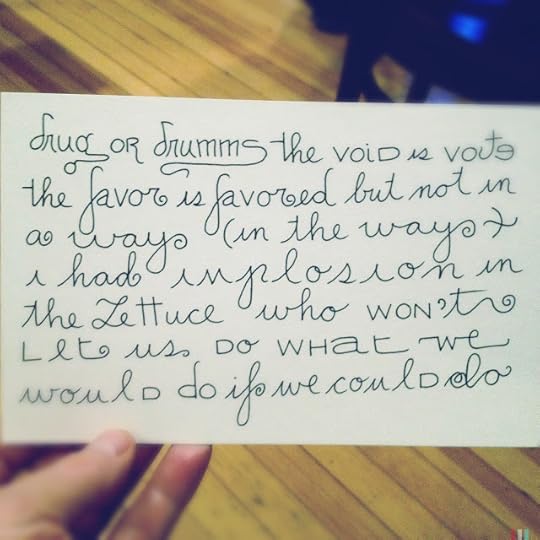

As the meeting was going on, I wrote a little poem, one modestly visual yet dependent on its visual presentation, and I wrote it but snatching words these young Democrats threw into the air. Pleasant words. Quiet words. Words they believed. And I made a poem that I think is wrawn well until its penultimate letter, which is where everything fell apart.

And I wonder if that flaw, if all the flaws within it, make it the poem it needs to be, the best poem this modest poem can be. Or if a flaw is just a flaw, something that tells you that you have nothing perfect before you and should move on to the next thing.

I bet the answer is the latter. But the former is the lie I want to believe.

(I had meant to slip into bed early tonight, yet I now see that it is nearly one in the morning, even though I would have guessed it was no later than ten. When we are entranced by words, by singing, by darkness and rain, by letters in a row, by white ice or clouds, by voices all around us, we sometimes forget where we are and who we are. And those are the times we wait for.)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 26, 2012 21:48

No comments have been added yet.