Our Stars and Stripes: A Symbol of Hope and Service

Flag Day

Being a descendant of Betsy Ross, the famous American flag stitcher, was part of my childhood legacy. Sons in the family still choose “Ross” as a middle name. I’m almost certain it’s not true, even though at least two branches of the Wilson family tree still carry the story. And the name.

Betsy Ross was married three times, the first to John Ross. They had no children. During her next two marriages, she had all daughters. One was married to a Wilson, but they don’t connect to the Wilsons in my family tree.

There was no American flag when our first ancestors came to the New World. There was no America yet when a couple of them signed their names to the Mayflower Compact.

Although none of my ancestors actually fought in the Revolutionary War, one sold provisions to the soldiers (and was disowned by the Quakers for that act) and another was a young drummer boy who helped guard prisoners of war.

The Betsy Ross Flag

After the United States of America was born, the Continental Congress established the Stars and Stripes to symbolize the new nation, on June 14, 1777, with one star and one stripe for each state. The stars were to be a symbol of the “new constellation.” In the flag known as the Betsy Ross flag, they formed a circle.

When Francis Scott Key wrote The Star-Spangled Banner in 1814, the flag had fifteen stars and fifteen stripes. The flag grew in size with each additional state, making it an unattractive shape, so four years later Congress decided the number of stripes would remain at thirteen but a new star would be added for each state joining the union.

Iowa became a state in 1846 and by the Civil War there were 34 states. During the Civil War, President Lincoln refused to let the stars for the southern states be dropped from the flag. By the time the war ended, two more stars had been added.

My most recent immigrant ancestors came to America in the 1870s, to escape having sons drafted to fight for the German Kaiser. The American flag was the symbol of the hope of their new life.

The 48-Star Flag

When the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag was first recited in public schools on Columbus Day, 1892, there were 44 stars in the flag. By 1912, there were 48. America flew the 48-star flag when at least four great uncles served in World War I, and when my father and several uncles enlisted for service during World War II.

When the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag was first recited in public schools on Columbus Day, 1892, there were 44 stars in the flag. By 1912, there were 48. America flew the 48-star flag when at least four great uncles served in World War I, and when my father and several uncles enlisted for service during World War II.

During my grade school years, each class recited the Pledge to the Flag, right hands over our hearts, before we began our lessons for the day. Congress added “under God” to the Pledge on Flag Day right after my fourth grade year.

I was in high school when the last two stars were added, for our new states of Alaska and Hawaii. The 50-star flag, the same one we honor today, represented our nation when my husband served in Vietnam.

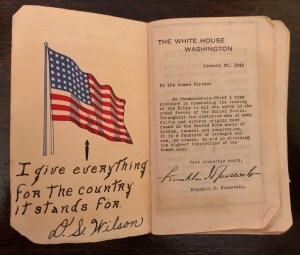

Danny Wilson’s New Testament

The American flag is pictured inside small New Testaments given servicemen during World War II. Beneath the flag in one small Testament, saved for decades by my Grandma Leora, in bold handwriting, it says “I give everything for the country it stands for. D. S. Wilson.” Danny Wilson, a P-38 pilot, was killed in action in Austria.

The American flag is pictured inside small New Testaments given servicemen during World War II. Beneath the flag in one small Testament, saved for decades by my Grandma Leora, in bold handwriting, it says “I give everything for the country it stands for. D. S. Wilson.” Danny Wilson, a P-38 pilot, was killed in action in Austria.

All five of the Wilson brothers served in World War II. Only two came home. When I fly the precious Stars and Stripes, I think about those three young brothers who were lost during the war.

I understand that the Pledge of Allegiance isn’t practiced in the public schools much anymore, and that patriotism is passe. Then it’s up to parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, friends and neighbors to make sure today’s youngsters know just what their freedoms cost.

Tell them why our ancestors were so anxious to risk everything to start over in this nation of hope, which is represented by the Stars and Stripes.